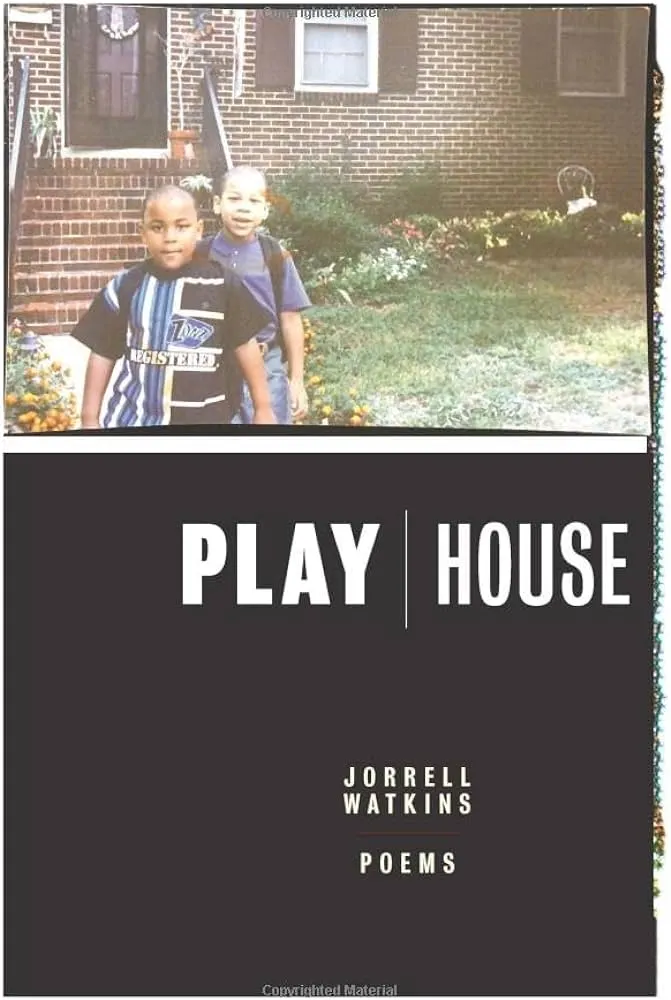

A Review of Play|House by Jorrell Watkins

Words By JP Legarte

*SPOILER ALERT* This review contains plot details of Play|House.

Published April 2024 by Northwestern University Press.

To say that Jorrell Watkins’ debut poetry collection Play|House contends with the troubling reality of being black in America would be an understatement that doesn’t do his work justice. Not only does Watkins unpack what it means for black boyhood and black psyche to succumb to drugs, guns, invisibility, and other intimate brutalities fostered by the U.S.—he also cultivates a curation where the poetry and music he cites are in conversation with one another. The music introduces figures such as John Coltrane, Ruth Brown, Nas, and Migos as another avenue Watkins simultaneously projects and confronts his boyhood and manhood while he addresses the historical and current injustices haunting black living. “I’ll play songs for you, something you can get with / we don’t have to talk, let music restore what we built” offers the first poem, “Brotha Speaks.” With language, rhythm, and structure that challenge traditional poetics as much as he challenges readers to bear witness to what he has witnessed, Watkins demonstrates his fearlessness to go for the gut when highlighting the hurt. Amidst his prowess, Watkins refuses to surrender to the violences perpetrated upon black living in America and, instead, celebrates the triumphs that originate from black joy.

With his ambitiousness, Watkins doesn’t ask readers to be patient when interacting with his unique dialect—he dares them to step into the cadence he knows and loves dearly. In “Acquisition: Mothership,” inspired by Parliament-Funkadelic’s “Mothership Connection,” Watkins riffs out, “Under the groove our steps collate minds / Maggot brain culture we kilowatt the bots / Overcharged, bail out systemic headlock / Bypass the rulers, circuit trip this business / One hundred and fifteen claps per minute.” Such language demands a reread, but this is not a criticism of the language itself. Rather, subsequent examinations of passages like this allow for a greater appreciation of Watkins’ deftness as he merges poetic and musical meters with commentary on America’s broken systems and how they’re broken. Watkins strikes just as hard with more conventional storytelling when a memory calls for it. In the poem “Up a Notch,” which follows him and his brother cooking a meal as a metaphor for pain birthed from creation, Watkins writes, “Concoctions made, teaspoons drawn, / which taste bombards the palate? / Jody’s nose bleeds, my throat peels. / [again] Emeril’s jazz band muses / his Cajun creation. Jody froths chili-mucus, / I hack heavy metal.”

Speaking of heavy metal, musical genre dictates both the poems and the three sections they are organized under, “House Below the Heavens,” “Halfway Blues House,” and “TrapHouse.” “House Below the Heavens” pays tribute to the hip-hop album Below the Heavens by Blu & Exile and situates readers within Watkins’ own house below the heavens—namely, insights into his childhood, adolescence, family, and reaching beyond cycles of harm to find black joy in a world that constantly takes it away. Meanwhile, “Halfway Blues House” borrows terminology from a living space known as a halfway house, a living environment that serves as the transition stage between incarceration, drug rehab, or mental health treatment and complete reintegration into independent living in society. The mixing of blues’ melancholy with the concept of the halfway house further juxtaposes Watkins and black living with the liminality imposed upon them. This leaves Watkins to question whether full healing is possible as joy and cycles of harm carry over from the first section. Finally, “TrapHouse” is directly modeled after its namesake, where illicit drugs are sold and used or where clay targets are released for skeet shooting. Here, everything Watkins tackles in previous sections culminates where he most explicitly confronts drug use, gun violence, and oblivion. One of the last poems, “Brotha Moves,” is a no-holding-back rhetoric on trauma sustained from police violence. Watkins recalls the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd and contemplates how he could just as easily be at the other end of an officer’s bullet.

Watkins’ amalgamation of “play” and “house” embodies poetic and personal maturity that not many debut writers can boast they have, especially considering the gravity of the issues and topics he faces. We see this playfulness intertwined with house in every sense of what a house can entail in “Up a Notch.” Similarly, to start “In the House,” Watkins writes, “Welcome to the most dreaded edifice of the living realm / where haunts whelm flesh into gastric muck and vultures / slurp the gutsy gunk. Watch your step.” Phrases like “gastric muck” and “slurp the gutsy gunk” showcase Watkins’ mastery of playing with poetic language while “Watch your step” and other horror-like descriptions like jet bats, a silkworm, and mercury bile paint a picture where escape is desired. In another poem titled “Mean what I say,” Watkins admits, “There’s three-fourths gallon pecan streusel bread / pudding on second shelf right door garage fridge. / Don’t know if nuts are too much, but it’s from / brotha-owned shop cross town.” From streusel bread to the literal haunting of a house, the oscillation between play and house makes the physical and emotional weight of being so close to these contrasting states of existence tangible as Watkins commands our attention from start to finish.

Play|House utilizes poetics and frames music as a muse to conjure a landscape where joy can be power in the face of America’s familiar obsession with cultures of drugs, guns, and invisibilities. This is not to say that joy is an absolute cure. Instead, Watkins poses moments of black joy that can build upon each other as growing triumphs amidst a reality that demands his people’s blood, sweat, and tears. Thus, joy is ultimately one form of survival, and Watkins shows no signs of slowing down in his disruption of hauntings, histories, and hellish systems. He issues his own challenge in “Brotha Moves” when he writes, “I’m not trying to be one seen on dark-mode dusked screens. Yo what Tupac say? I aint one to push but if pushed, watch how far I go.”