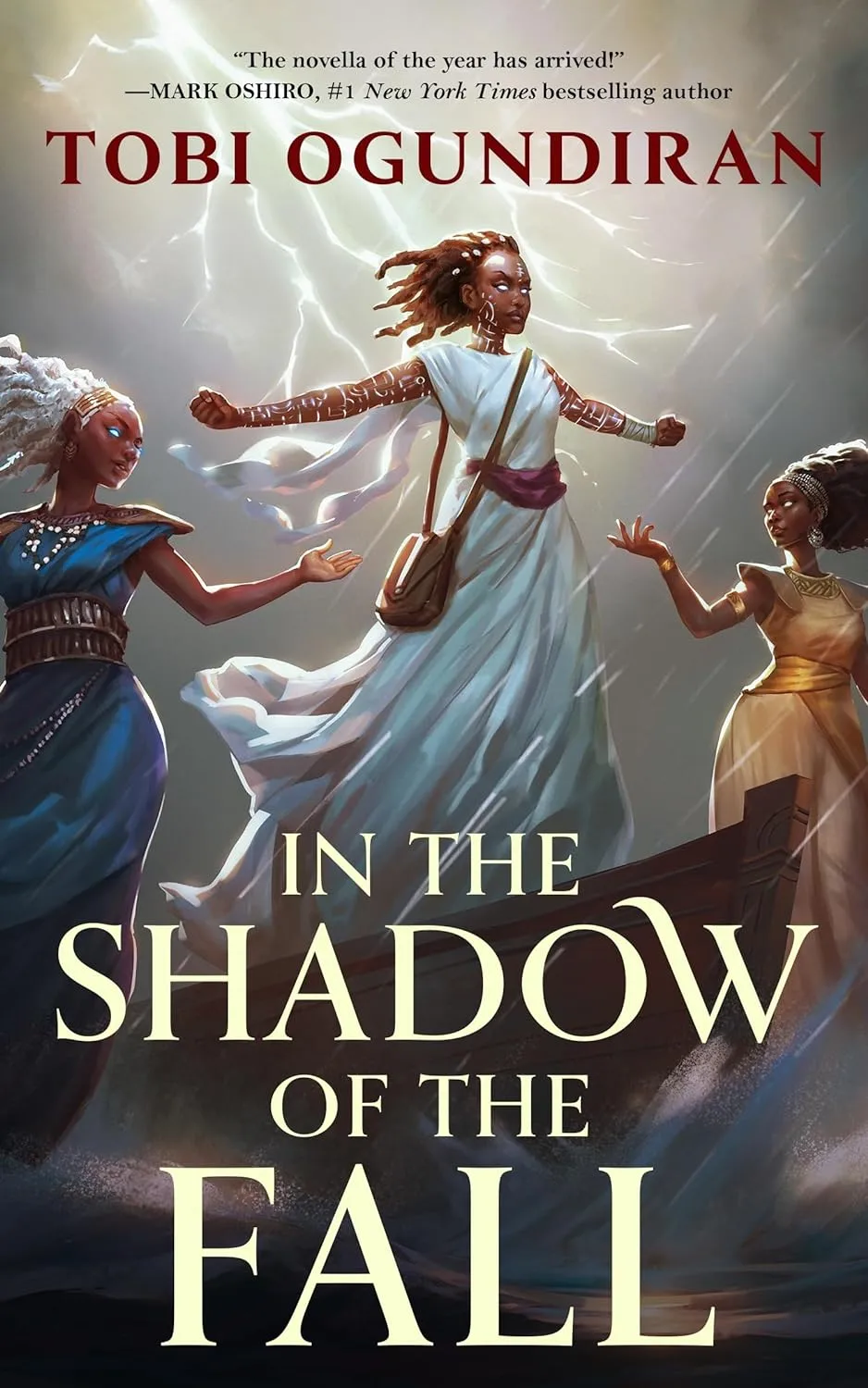

A Review of In The Shadow of the Fall by Tobi Ogundiran

Words By Stevi Sargas

*SPOILER ALERT* This review contains plot details of In the Shadow of the Fall.

It will be published on July 23, 2024 by Tordotcom.

Tobi Ogundiran’s In the Shadow of the Fall delivers a compact yet powerful exploration of self-discovery in a magical, African-inspired world. Despite its brevity as a novella, Ogundiran’s debut excels with vivid character development and absorbing worldbuilding, offering readers a fresh twist on genre expectations of Eurocentric fantasy. The story traverses culture and identity through the eyes of Ashâke, an upstart, failed acolyte who brashly attempts to summon the orisha, gods of the West-African Yoruba religion, for her own purposes. This sets off a chain of events that plunges her into a sprawling journey to uncover the truth about the world and her place within it. Comparable to N. K. Jemisin, Ogundiran’s voice is gritty, but the narrative retains a gripping mystique. It strikes an intriguing balance between the contemporary surge in low-fantasy titles and classic tales of epic gods and mythologies, making for a fresh change of pace.

The standout gem of In the Shadow of the Fall is its African worldbuilding, which serves as the vibrant tapestry against which Ashâke’s personal narrative unfolds. Ogundiran weaves elements of folklore, mythology, and African culture to create a setting that feels authentic and enchanting. The textual communication of oral tradition in the story is an admirable feat as Ashâke learns of her heritage through song. This a transformative, spiritual experience that readers are easily able to pick up as they read along. “Jaha stepped into the circle, spread his ample arms wide, and bellowed to the heavens…The world fell away. The griots, the trees, the fire…then the world burst to colour before [Ashâke].” We are buoyed by Ogundiran’s expertise as he plunges us into a new world of vital and tantalizing images.

In the Shadow of the Fall’s magic-brimming world is paired with impactful prose, highlighted particularly during action scenes. Whether it’s a pulse-pounding chase through the forest or a retelling of a creation myth, Ogundiran renders plot beats with cinematic flair. “Several bolts of lightning fractured the heavens, terribly in their beauty…A bolt forked through the Tower. The top half shifted, teetered on its edge, then with a great groan, shattered.” His writing is bold and evocative, painting striking images that linger in the mind. In these moments, Ogundiran’s talent as a storyteller is on full display, immersing readers’ senses and leaving them hungry for more.

Through the eyes of young Ashâke, readers are introduced to a diverse cast of personalities: the eccentric Ba Fatai, the high priestess Iyalawo, and chief Mama Agba, who guide Ashâke on her journey of self-discovery. These characters are vivid and visual, springing to life in just a few sentences. Due to the succinctness a novella’s word count demands, they can at times feel tropey, although, perhaps only because Western literature has already made caricatures of these types of characters. Ogundiran’s work arguably humanizes these tropes by contextualizing them within their own culture and giving them their own motives. We know Ba Fatai and Mama Agba are meet-the-mentor and fairy-godmother-type characters. Leaning into these assumptions while giving the characters a striking visual identity orients us quickly and seeds our expectations for the role they will play. Ogundiran then promptly spring boards us into more nuanced, informed character expression—a territory into which I was more than happy to be flung. My only gripe is that I desperately wanted to know more about these characters.

There are moments where In the Shadow of the Fall’s feels constrained by the same economy of language that sets it apart. Take the description of the griot encampment Ashâke encounters after escaping the temple for example: “Eight huge boats idled in the river. Each vessel was onion-shaped, their hulls covered with brightly painted whorl patterns…It looked like a floating city.” I read this and want to know, has Ashâke heard of griots before? What kinds of whorls are painted, and what might they represent? Who fashions the griots, and from which resources? It’s important to consider that I don’t see these answers because I am unfamiliar with African history. I read the word “whorl,” and think it’s describing a shape: a swirl. It may be a culturally significant symbol, like my own koru—an indigenous swirling pattern used in New Zealand Māori art—and I am only scratching the surface of its meaning. With a higher word count to play with, Ogundiran may have built on these frameworks and further showcased his potential for introducing an underrepresented culture to a broad audience.

The novella could also have benefitted from more socio-political intrigue. The psyops of belief is pivotal to the story’s gods, the orisha, and to Ashâke’s self-discovery. Who holds the power to control information for the masses is an important question that was not wholeheartedly answered by the book’s end. While Ashâke is sheltered and primarily concerned with her identity, this naivete could have been used as a blank slate from which to launch her—and the readers—into the subversive realm of the book’s politics and religion, giving us a broader view of the forces at play when magic meets man’s lust for power.

Qualms aside, In the Shadow of the Fall is a refreshing debut, and a testament to Tobi Ogundiran’s talent as an emerging writer. He blends intricate worldbuilding with compelling, character-driven storytelling to create a debut that is pithy, culturally crucial, and filled with mystical allure. While the novella may leave readers yearning for a deeper exploration of its world, its strengths lie in the same place—a richly imagined setting, nuanced characters, and vibrant prose. Fans of fantasy and adventure will find much to love in this captivating tale of old gods, found family, and identity.