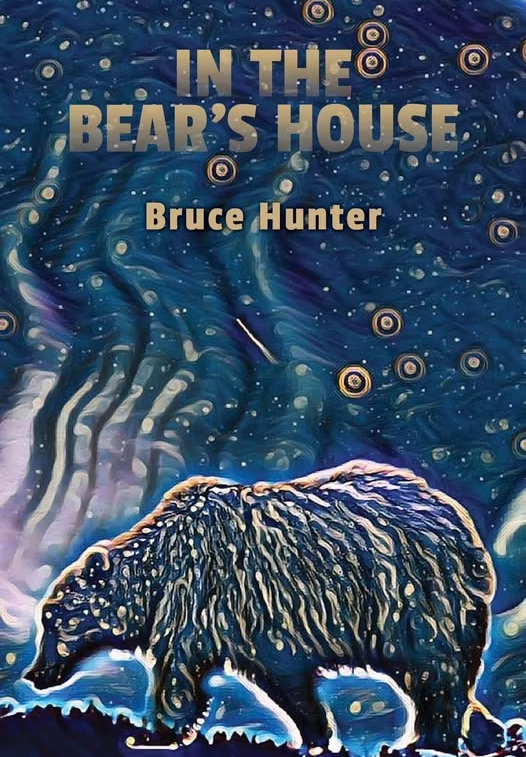

A Review of In the Bear’s House

Words By Ainsley Louie-Suntjens

This title was re-issued in May 2025 by Frontenac House.

My discovery of In the Bear’s House came at an eerily apt time. I started reading it on a plane to Glasgow, flying out of Calgary, Alberta. As I read deeper and flew further and further from my hometown, I realized I was traveling the reverse of the characters in the book: out of Glasgow, into Calgary. As I traversed the highlands on various motorcoaches and taxis these characters wandered the prairies and mountains of Western Alberta, down streets and train lines I walked myself; it was the perfect antidote to any possible homesickness that could have afflicted me.

In The Bear’s House is a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman by Albertan author Bruce Hunter. It follows two narrators, Clare Dunlop and her partially deaf son, William “Trout” Dunlop, as she attempts to raise Trout as a teen mother, and he tries to make sense of a world not particularly interested in making sense of him. Clare grows into herself as not just a parent of four, but a woman—finding work, getting an education, discovering her voice. As Trout gets older, he retreats, both figuratively and literally; he goes to stay with his Aunt Shelagh and park ranger Uncle Jack, who’s also partially deaf. On their homestead in northwestern Alberta, he truly meets the land, and its people, for the first time. Hunter explores growing up in a land and country still growing up itself, finding place, finding home, and finding self.

Though originally published in 2009, Frontenac House reissued In The Bear’s House in May 2025, and I can’t think of a better time to do so. Calgary is changing, again. From “Feel the Energy” to “The Blue Sky City,” we as Albertans, as Calgarians, are trying to decide who we are going to be in a rapidly changing world. Albertan writer, academic, and someone I have been lucky enough to learn from, Dr. Aritha Van Herk, posits that Calgary, and Alberta, are places that don’t yet know themselves, and may never know themselves. We have no clear and recognizable identity, at least not yet. This state is one Hunter captures exceptionally well, particularly through his two narrators. Trout is a boy born in the city, but is drawn to the traditional, rural ways of the land. He finds solace chopping logs, maintaining access trails, snowshoeing with Jack, and tending the garden with Shelagh. In the wilderness his hearing aids are not overloaded; he finds a sense of independence and peace he was never afforded in the city. This representation of disability is a wonderful breath of fresh air. Hunter, who is deaf himself, recognizes Trout’s partial deafness as a fundamental part of who he is, but allows Trout to find competences, ways of knowing, and an identity beyond that. Meanwhile, Clare is initially set up as a traditional stay-at-home wife and mother but slowly sheds that role and becomes increasingly cosmopolitan and outgoing. She emerges from her shell attending night classes, befriending local Greek immigrants and a queer couple, even re-involving herself in the local literary scene after her own poetic inclinations were sidetracked by the birth of Trout and his three sisters. Her journey was its own coming-of-age story, and so often mothers in fiction, and reality, are not afforded that degree of agency. Clare is a loving and supportive mother, but is also a voracious reader of poetry, an adventurous chef and foodie, and a committed peripatetic.

Hunter also captures the variety of this city, and this province extremely well—every one of these characters, I have met before. With Alberta, Calgary in particular, stories can become all cowboys, teepees, and oil men quickly, and Hunter appreciated those elements are only one part of the story. He highlights everything from Trout and Jack’s deafness to local Indigenous groups, to its thriving Chinese community, and even the diversity of the land. Again, Hunter hones in on the idea that the Albertan identity is patchwork but also recognizes there is no way around it. The bell cannot be unrung, so it is up to us to sort it out.

One facet I do have questions about from In The Bear’s House is how Hunter explores Alberta’s local indigenous population: the Kainai, Siksika, Piikani, Tsuu T’ina, and Stoney Nakoda, consisting of the Chiniki, Goodstoney and Bearspaw. He consulted with local elders and clearly did his research, which I commend, but I wonder about the storytelling choices made. As Trout spends time with Uncle Jack and Aunt Shelagh, he meets Carrie Moses and her grandfather Silas, based on real Goodstoney leader Silas Abraham. They invite him into their tribal traditions—the Sun Dance, the Ghost Dance, and their burying grounds. As Trout becomes familiar with their ways of living, the construction of what is implied to be the Bighorn Dam threatens their land—particularly their burial grounds—which will flood upon construction. This point never achieves resolution in the novel. From both my own research and living in Alberta my whole life, the Bighorn Dam was indeed completed, resulting in the creation of the Abraham Reservoir; horribly enough, named after Silas Abraham, who opposed its creation his entire life. I wish the Stoney were afforded some degree of closure narratively—it doesn’t have to be revisionism, but about three-quarters through the novel that arc was dropped, and I found it jarring. Interpreted good faith, it felt like the story moved on from them; in bad faith, it felt like it forgot about them.

The title of this novel is pulled from a quote from Hunter’s Great Uncle John Elliot, who served as the inspiration for Uncle Jack: “We are in the bear’s house now. Mind your manners.” To fully grasp this story, one must approach this novel in the same way. It is firmly rooted in our land, our people, and our literary tradition—some learning may be required (I recommend Robert Kroetsch, Aritha Van Herk, and Joshua Whitehead), background viewing even more required; ideally out of a car window, at the Three Sisters Peaks, or perhaps the prairie on the way to Drumheller. As I said, this re-issue couldn’t have come at a better time; as we re-appraise what to do with our land and how the people on it can live, fully and with respect, In The Bear’s House is an important reminder that we are not just the oil country, the Blue Sky City, or the home of the Stampede, but we are, first, in the bear’s house.