A Review of For Now by Eileen Myles

Words By Kennedy Coyne

Published on September 22, 2020 by Yale University Press

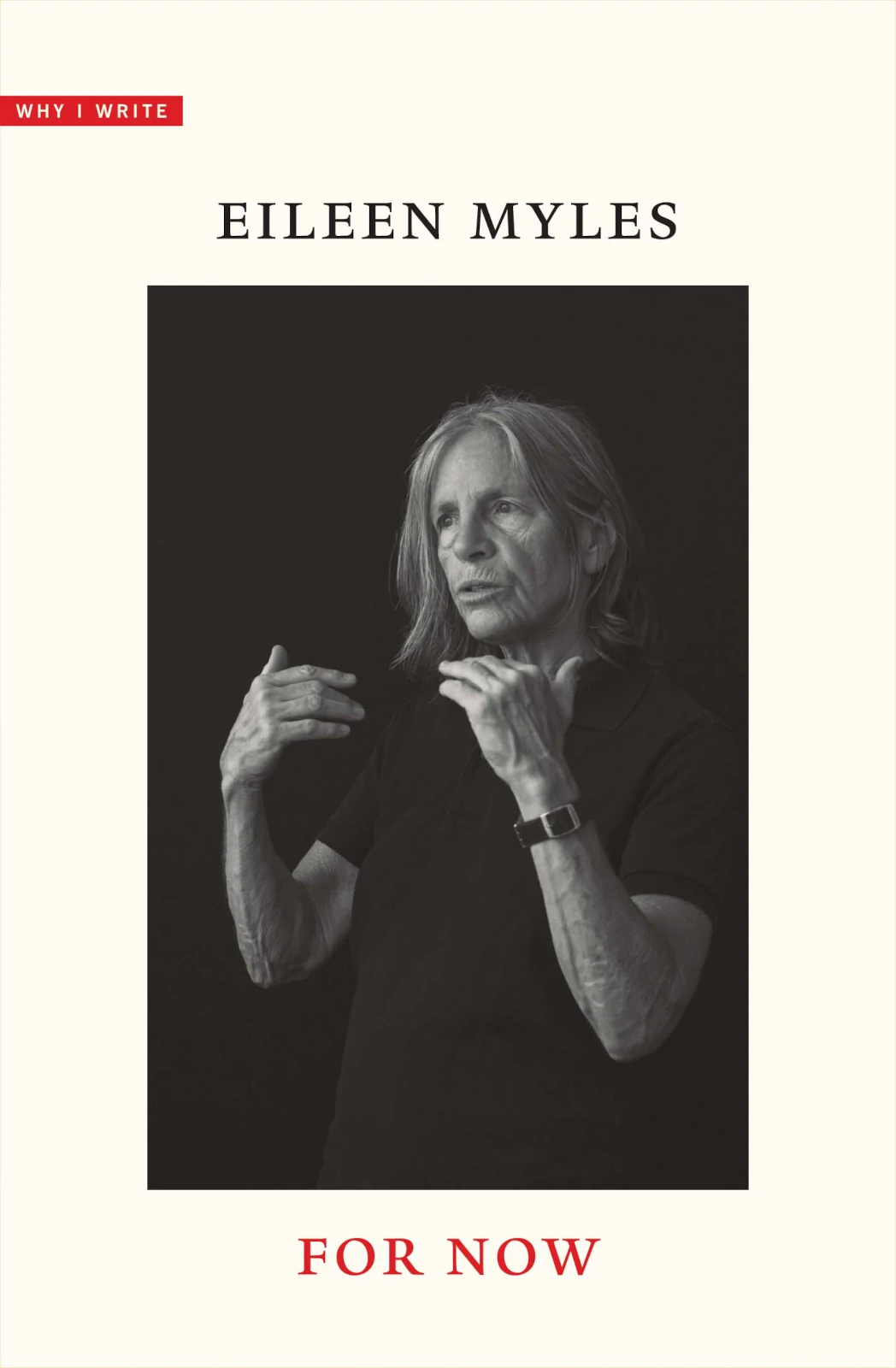

When you’re holding Eileen Myles’s new book For Now (from Yale University Press’s “Why I Write” series), it’s hard not to think of their 1980, black-and-white, Mapplethorpe headshot on the cover of Chelsea Girls. A young, androgynous Eileen, with a stare somewhere between coy and doe-eyed, suggests they know something you don’t. Forty years later, on the cover of For Now, this Eileen doesn’t look at you, but instead they seem to engage with someone else beyond the frame. They’re mid-conversation. They look—to use the title of their 2000 novel—too “cool for you,” wearing a wristwatch with the face turned in, their hands gesturing up explaining something, working through something. It’s a tease: What are they saying, and who are they saying it to?

Those questions soon disappear as you read not just words on a page, but Myles’s intimate thoughts in their present moment. For Now isn’t a self-aggrandizing book in which Myles praises and reflects on past work and accomplishments. It isn’t filled with dense language or conceptual ideas of writing. Myles doesn’t offer tricks of the craft or tell us what we should be doing. Instead, they let us sit with them while they’re writing and thinking about why they write. We accompany them through a myriad of temporal and physical spaces, jumping in time from being a child learning how to ride a bike, to being stuck in Texas during the pandemic with only their dog, Honey, for company. The constant movement in time and space can feel disorienting, but the motion, the speed, and the rhythm with which Myles tells their story invites us to stick around for the ride.

The pages in For Now are honest, like we’re simultaneously inside Myles’s head and having a conversation with them. Maybe it’s the way they resist traditional narrative form, disrupting grammar and mechanics: they omit commas; they use single sentences that span the length of whole pages. Myles even pokes fun at the arbitrariness of it all:

Questions marks are hysterical. I’ll use one.

Maybe it’s that we know exactly where they are when they write. They tell us what their 300-square-foot apartment looks like: “pathetic,” with “bumpy” walls, the “built-in” bed “jammed right up against the window,” and items scattered across a desk which is really a kitchen table. Nothing is held back, even the seemingly meaningless details of what they’ve written on and written with:

I wrote on napkins and I wrote on cigarette packs I wrote in tiny notebooks of all kinds and I wrote on legal pads. Ideally I wrote with a nice thick runny pen, a rolling writer, originally a pentel. It’s moved on to being a Pilot G-2 otherwise known as bold. I like fine you might say. Well I pity you.

Maybe it’s that Myles simply writes their stories, narratives, and poems for an audience who wants to read them. This provocative, unvarnished transparency is why I find their work so compelling.

Like their other works of prose, Myles doesn’t keep us stationary in one chronological narrative for long, constantly shifting anecdotes, memories, thought processes. Just as these elements begin to swirl together and we find the pages turning faster and faster, Myles stops the reader to say:

I’m going to catch you up. I’ve written half. Actually that’s not even true. I’ve written one-third. Which is horrifying.

They don’t romanticize this confession. It’s brutal and relatable—one of the few moments they signal the reader to stop for a second and breathe, take in their writing. It’s satisfying to see Myles—who appears to write with ease—admit that maybe they don’t see an end in sight, that maybe it’s frustrating to consider why they write. To be fair, at times it feels like Myles only wrote this book because Yale asked them to, and then resistantly, because Myles’s core identity as a working-class poet is not a natural match for Yale’s institutionalized wealth.

In pandemic times, you can’t go see Myles read in person, but you can listen to their Aloha/irish trees LP or watch their readings in the depths of YouTube. I can tell you that when Myles performs, it’s uncanny in its ability to sound so unlike a staged reading. They lean into it, hands pushing the words forward, head cocked to the side with hair falling in their face. They are submerged in their work. Active. In motion. Myles—mid-movement on the cover of For Now—positions the reader as the one in conversation with them, allowing us to insert ourselves in the ever-present “you” that they drop in throughout the book, to ride the handlebars of their bike through a narrative that talks about more than writing, but reading and living, home and movement, and absurdities like question marks. It places Myles in the right-now but also in the back-then and what’s-next.

For Now is one of Myles’s most inviting pieces of writing. At less than one-hundred pages, For Now makes it easy to enter into their world, offering an opportunity to know Myles in all of their intricacies and intimacies. It’s a treat for those familiar with Myles’s work, but could also serve as a representative introduction for those just finding it. After reading For Now in one sitting—because I couldn’t help but eat it up all at once—I found myself revisiting Myles’s past work—Chelsea Girls, Snowflake/Different Streets—because as lovely as For Now is to read, it leaves a hunger for more.