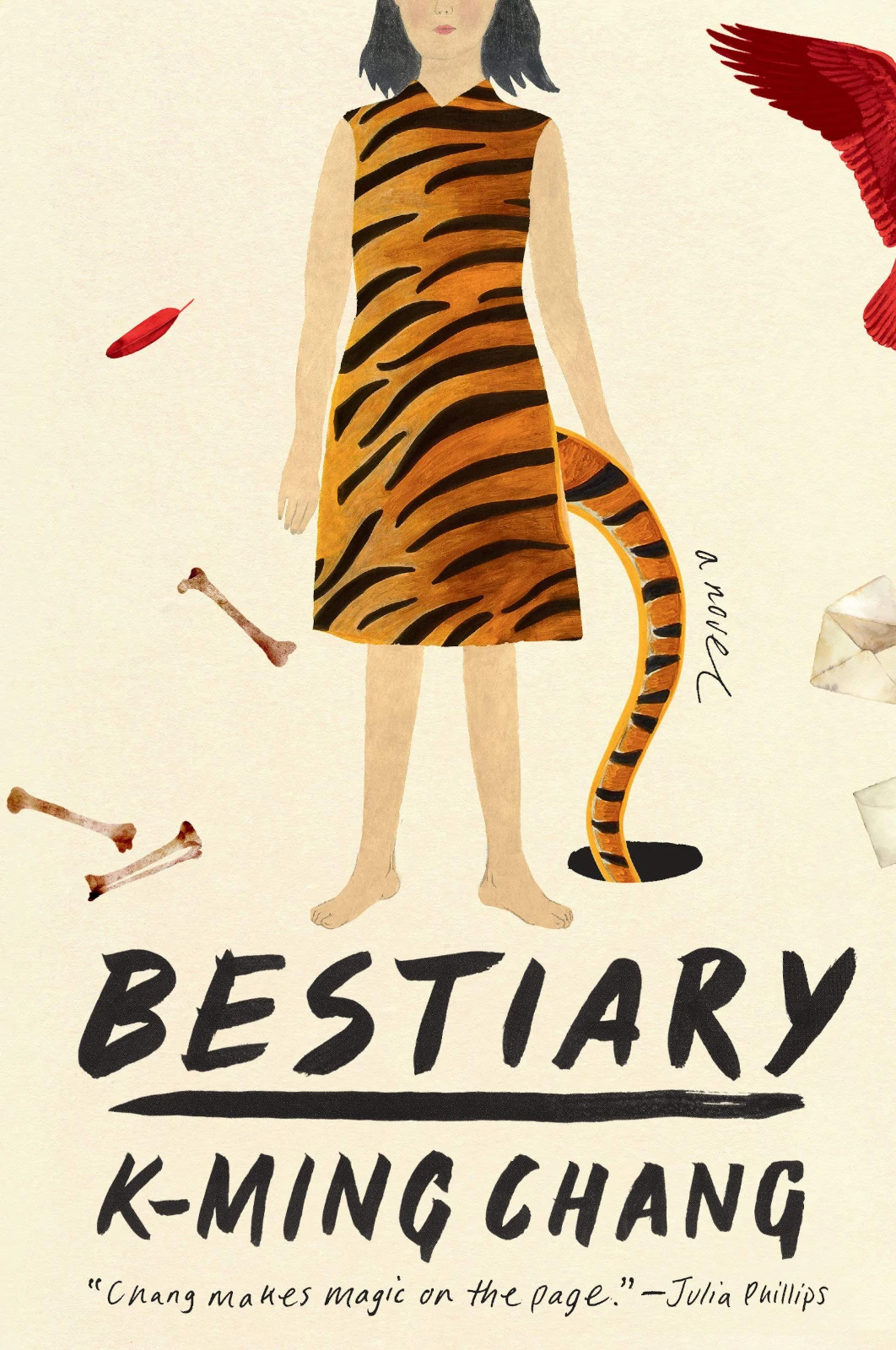

A Review of Bestiary by K-Ming Chang

Words By Aoife Lynch

Published on September 29, 2020 by One World

K-Ming Chang’s debut novel, Bestiary, is truly unique. It’s a ferocious, passionate book that uncovers a queer, female lineage within the Taiwanese folklore tradition. Three generations of women—Daughter, Mother, and Grandmother—push against the boundaries of the roles and mythologies they have inherited. These three perspectives migrate across country borders, state lines, and languages. The novel blurs the distinction between story and history and creates new, provisional narratives of being. The novel pairs magical realist elements with a persistent emphasis on the mechanics of bodily existence. Chang insistently reminds her readers of the porous nature of our bodies, questioning the division between the beautiful and the gross, the profound and the taboo.

The central plot of the novel begins in California when Daughter grows a tiger’s tail. She becomes connected to Hu Gu Po, a tiger-spirit who is the focus of one of Grandmother’s stories. As Daughter falls in love with a girl called Ben and uncovers a queer, woman-centered family mythology, she reckons with the hunger, desire, violence, and nurture that constitute her own daily bodily existence, and the bodily existence of women more generally. K-Ming Chang explores a fragmented linguistic and cultural history, both within and beyond Taiwan, in order to create a woman-centered, fabulist, and transgressive inheritance of stories. It’s exhilarating.

Hu Gu Po is the protagonist of a Taiwanese folktale about a tiger-spirit in a woman’s body who sneakily eats human toes like peanuts. This tale anchors the novel. Hu Gu Po is an example of how a narrative can have many versions, how all stories need someone to question them, and how violence is as much a part of a woman’s inheritance as the ability to nurture. What feels bold and exciting about K-Ming Chang’s version, and Bestiary as a whole, is that there’s no external punishment for wild women or the wildness of Hu Gu Po. Instead, hunger is shown to be part of womanhood. Bestiary is a retelling of the Hu Gu Po story from the tiger-woman’s perspective, a reclaiming of the perspective of the hungry, wild woman.

K-Ming Chang’s writing of the relationships between women, from familial to the romantic and erotic, is a revelation. Bestiary writes familial love—a mother’s love for her daughter—in a way that exposes a physicality and hunger that’s often only ascribed to erotic love between women.

The relationship between Ben and Daughter is truly special. It’s unlike any other depiction of love between girls that I’ve read. Chang has created two girls in love who are utterly without shame. There’s a boundlessness and freedom to their desire, a joy and a ferocity, that’s incredibly exciting. K-Ming Chang captures the wonder, adventure, and discovery present in sexuality and desire. For Ben and Daughter, sex is a kind of transformation. It’s explored in the same visceral and surreal terms as everything else in this remarkable novel.

Bestiary questions the divisions between things, from the border between folkloric and real worlds, to the blurred space between languages, to the binary that’s upheld between beauty and disgust. Urine becomes a “piss-river” that “runs straight into the house and floods it with fermented sunlight,” stars flake off the sky “like dandruff,” and the soil is a “tapestry of worms.” Most striking is K-Ming Chang’s incorporation of the taboo actions and parts of the body within desire and love. Sweating armpits, flakes of dried spit, even a “pebble of dried mucus” dissolving on the tongue, are all within the jurisdiction of desire. K-Ming Chang seems to ask: why should only some parts of the body, some bodily fluids, be part of sexuality? Why must we ignore the minutiae of physical intimacy? Bestiary rewrites the rules around how we express desire.

I think it’s worth saying that I didn’t know much about Taiwanese history or folklore before reading Bestiary, yet the novel still felt rich and complex despite my ignorance. K-Ming Chang does a wonderful job of unpacking the intricacies of Taiwan’s fragmented linguistic and cultural inheritance in a way that’s accessible to people who aren’t familiar with Taiwan’s history. Bestiary challenges the idea of a singular narrative about the past. Instead, K-Ming Chang creates a polyphonic history that makes folktales and authorized narratives stand side by side, lets different languages rub up against each other, and acknowledges absence. Bestiary includes those who have been left out by official narratives about Taiwan’s past. Yet despite the novel’s ambition and nuance, I didn’t feel bogged down by what I didn’t know. K-Ming Chang’s updating of traditional folktales and history within a new time, context, and language felt emotionally and conceptually resonant.

K-Ming Chang is a poet as well as a novelist, and it shows in her writing. Daughter receives mysterious letters throughout the course of the novel from Grandmother, and these letters are strange and moving poems in their own right. In Grandmother’s poem-letters, K-Ming Chang adopts a more pared-back style, exposing the strangeness of language. Sometimes, though, the richness of Bestiary’s prose can become too decadent and dense, particularly when K-Ming Chang pairs this decadence with a constant delighting in grossness. It’s not that K-Ming Chang’s language is too flowery—it’s relentlessly physical and expressive in a way that can become overwhelming, and occasionally frustrating.

Bestiary is a strange and moving book. Sometimes partially due to and sometimes despite its aesthetic of richness, grossness, and excess, Bestiary is a really remarkable debut novel. K-Ming Chang rewrites the terms in which we read queer girlhood and migrant narratives, and I’m so excited to see what she does next. Wherever K-Ming Chang goes with her writing, I know I’ll be following, discovering new joyful, wild, and tender ways of existing in the world.