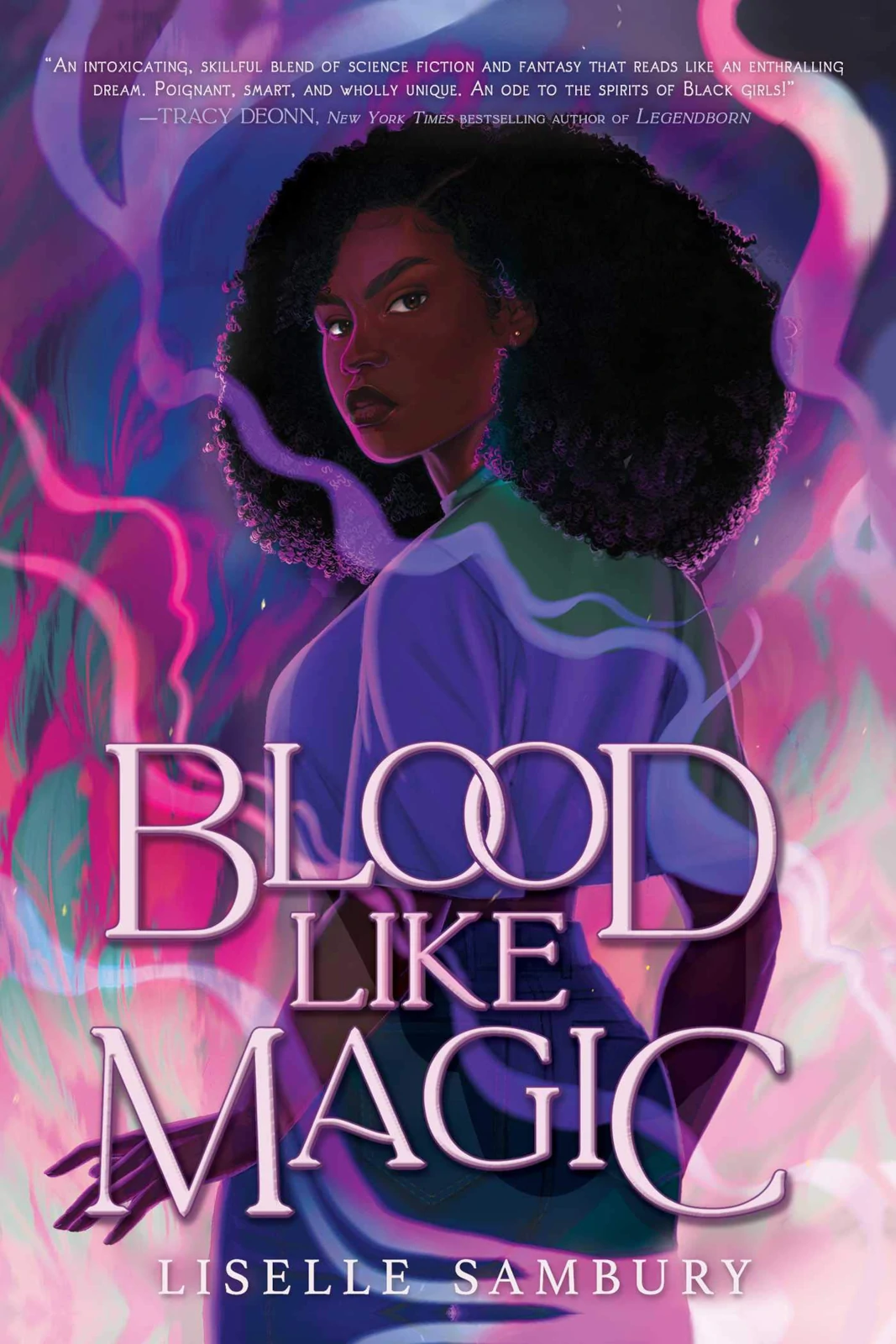

A Review of Blood Like Magic by Liselle Sambury

Words By Esther Hsu

Published June 15, 2021 by Margaret K. McElderry Books.

Liselle Sambury’s debut novel, Blood Like Magic, combines the allure of hidden magic and advanced technology set in a not-so-distant future. The story revolves around Voya, a witch tasked with finding and destroying her first love in order to receive full witch power from her ancestors. This book promised an engaging plot via a Black-witch fantasy, LGBTQ+ representation, strong family focus, and a unique hate-to-love romance, but it doesn’t quite deliver on most of these promises.

The book aims to bring marginalized identities to the forefront with a Black-girl protagonist and a myriad of LGBTQ+ characters. But the way Sambury talks about certain identities, especially the transgender community and Asian community, seem to perpetuate microaggressions that these communities already face daily. For example, one scene in the book revolves around Voya wanting to avoid a conversation about her Calling (the revelation of what her task is) by deflecting the focus away from her and towards Alex, her transgender cousin, and Alex’s “Bleeding” (the initial onset of witch powers via literal bleeding), even though Alex obviously does not want to be the center of conversation nor want to share. This kind of microaggression pits a hyper-focus on the stories of trans and gender-expansive individuals, using their personal stories as ways to avoid uncomfortable or unwanted conversation without the consent of the individual themselves.

Another scene shortly after involves Voya assuming the genders of three people she sees on a stage, blatantly labeling them as boys or girls. Yet, in the very next sentence, she wonders if the emcee will reveal their pronouns so that she can “adjust” her language. The irony in this is that she’s already assumed these characters’ genders and yet still half-heartedly attempts allyship by hoping to use the correct pronouns. These moments of flawed allyship, moments that don’t directly affect the plot trajectory of the novel, could have been easily avoided.

Additionally, the novel’s language surrounding Asian food perpetuates Asian culture and food as foreign. This is most explicit when the book doesn’t find the need to explain the origins of certain foods like pelau, but the need to do so with Asian dishes like adobo.

The pacing of the novel was also affected by arbitrarily thrown-in details that seemed unrelated to the plot. Not only does the book explicitly tell the reader the characters’ feelings rather than showing them, it also tosses around details about race and gender that serve no point in the story other than to mention it. The mentions of these identities seemed to be diversity fodder—a way to check off and ascertain marginalized identities in the novel. This does a real disservice to the profoundness of these identities by not giving these characters more substance than just a name and identity label.

All of this builds into the book’s problematic themes, two of which this review will briefly discuss. The first is the idea that painful experiences build character, which can be completely true—unless this involves watching a child relative drown in a freezing lake and lose two toes for the sake of “building adversity.” Or, forcefully (without deliberation or consent) taking away any chance a beloved cousin has at being able to fulfill her dreams because the characters know she has the strength to create a new future. This is supposedly the novel’s promised “strong family focus—instead, it screams of a family that very aggravatingly refuses to communicate—a damaging family trait that causes and perpetuates about 80 percent of the plot points in the story.

The second theme regards the intent vs impact discussion throughout the book. The story somehow focuses on intent being most important. Voya, at the end of the novel, says, “We decide who we are, not the magic we practice. And I need to trust myself enough to know, however I choose to use my power, it’ll be for the right reasons.” So this leads the reader to the problematic conclusion that . . . it’s okay to kidnap and kill people in rituals? Or, it’s okay to use magic to chain a person to a house? Or, it’s okay to brush off the fact that a family needlessly participates in a murder ritual because of the family’s poor communication? The answer to all these questions is yes, because it’s for the family’s sake and safety. And while the end of the book tries to focus on how “being [pure] or [unpure] doesn’t preclude you from being morally right or wrong otherwise,” it also entirely contradicts that point by very clearly painting specific characters as morally wrong and others as morally right – for example, the book condemns those who commit murder for science but doesn’t for those who commit murder to save the family’s magic. This could just be a great build-up for an extremely satisfying redemption arc in the confirmed sequel—but as it stands, the book paints Voya and her family more as antagonists.

With all that said, Blood Like Magic does have its upsides. The magic and worldbuilding are extremely compelling, particularly the ways that magic and technology coexist in this advanced society. The author also chooses not to front-load readers with worldbuilding information and slowly reveals new gadgets, new inventions, and changes in this world one by one in an extremely captivating way. And the magic/technology theme isn’t without nuance. Sambury skillfully incorporates examinations of class and socioeconomic status into her novel, highlighting the ways in which advancements might further certain inequities. Interwoven into this is an analysis of immigration and international adoption, shining a light on the multiple perspectives involved in such policies.

The flaws in Blood Like Magic don’t outweigh the positives, but we can look forward to Sambury’s future work. Sambury isn’t afraid to explore topics that other authors often sideline, and while there may be fumbles at these attempts, these attempts also leave the reader with great anticipation of the growth that we will see in her sequel and subsequent novels.