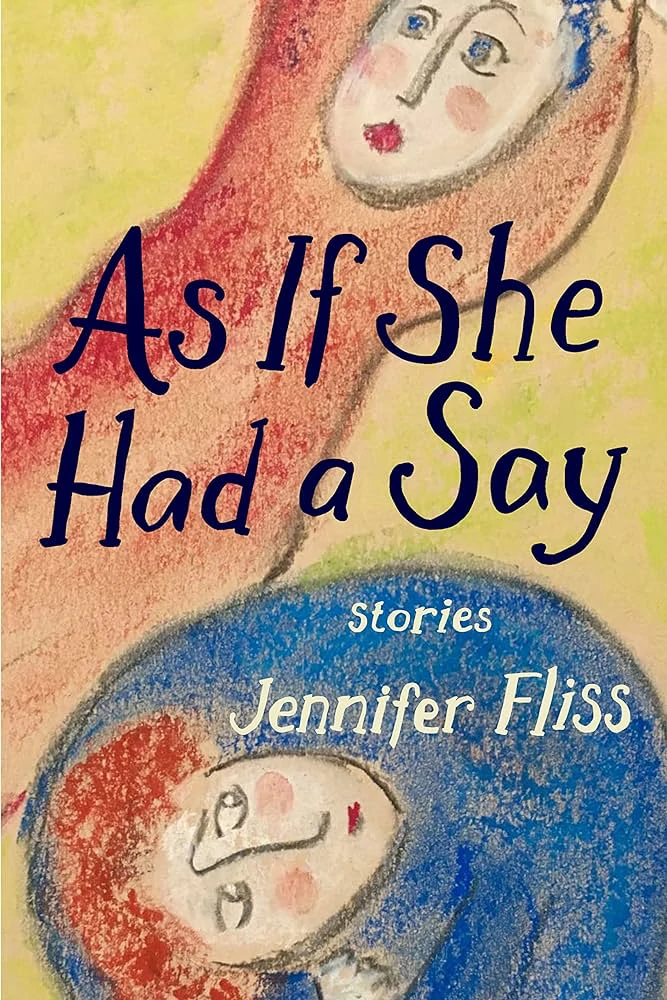

A Review of As If She Had a Say by Jennifer Fliss

Words By Sam Burt

*SPOILER ALERT* The following review contains details about As If She Had a Say, published July 2023 by Curbstone Books.

There are at least two ways to interpret the title of Jennifer Fliss’s second story collection. “As if” can connote both denial and imagined possibility, an acknowledgement that her female characters’ lives were far from freely chosen and the hope that that might change in future. Hope, in fact,characterizes the closing note of many of these pieces, which favor ambiguity over neat endings and easy answers–and are all the stronger for it.

The stories vary by genre, combining the fabulous (women turning into water, tiny women who inhabit fridges, a shop where you can buy new hands) with realistic pieces, and some experimental formats (one story is written in the passive-aggressive voice of an eviction notice). However, as with writers like Carmen Maria Machado, with whom Fliss has been compared, reality is not being twisted here for its own sake, but in order to show its many facets more clearly. For all its formal diversity, the collection is bound by clear, recurring themes. Many characters have lost a partner or a parent, and Fliss’s fascination with how grief manifests differently for all of us is evident. In “Pieces of Her,” for example, we see a recently widowed man find a lock of his wife’s hair in the shower and tape it to the bathroom wall, while in “The Cresting Water,” an older woman refuses to abandon her home in the face of flood warnings, believing a reunion with her late husband is imminent. In Fliss’s hands, the private, taboo-like nature of grief and loss proves to be rich material, with fiction providing a space to say the unsayable.

Parental bonds also feature heavily, with parents trying and often failing (or not even trying at all) to connect with their children. In “Losing the House in D Minor,” a child is reunited with her mother but realizes that, “…it wasn’t me that my mother cared about. It was baby-me…the me she’d held onto when I cried as a toddler. […] the living-and-breathing me, she wanted nothing to do with.” In another story, “Winter Rebirth,” we see something similar from the perspective of a mother who is breastfeeding her newborn and wondering if its father will ever return: “The mother, in that moment, feels like a mother, but then she looks away and doesn’t.” The world of these stories is one in which parents are not always reliable caregivers. The worst of these fathers embody a type of abusive male who uses caregiving to mask the exercise of coercion and neglect, as in “Splintered,” where a woman recalls her father seeming to relish the mutilation of her young body in order to save her from a splinter: “You might have to get amputated, he’d said. Cut it off completely or it will become infected. He had come at her with a sharp object, its tip and his eyes glinting.” Throughout, Fliss is attentive to the more subtle, everyday sleights of hand by which men make women feel objectified.

Still, even in the stories which should be the most depressing, she finds a way to gesture towards hope, however small and tentative. In one piece, a rape victim showers in her clothes after the event because “you cannot imagine looking at your body as you once did. As your own.” Through this act, however, she comes to realize “there are corners and crevices of your body that are inaccessible, for you alone to reach.” This is a fairly typical ending for Fliss, which manages to avoid cheerful, lazy optimism while grounding hope in uncertainty and counter-narrative. Elsewhere, we find men capable of reflecting on their blind spots vis-a-vis women and adopting a more inclusive, less male-centric worldview. On finding a tiny woman living in the fridge of his now ex-wife, Amos asks: “Were there always women in the corners and crevices in the world that directed life? Was their purpose to go unnoticed? But he had noticed her.” A male writer loses most of his hearing and finds the usual ties between specific words/concepts and sexes/genders has dissolved: “you’ve decided that it’s not a bad world to live in: a world where men and women don’t always do what you expect them to.” Selective hearing abounds in how these men deal with the women in their lives, but it need not be so.

Inevitably, not all of the stories are as satisfying as the best among them. There were times when I sensed the author holding back from explaining things or drawing connections, perhaps for fear of making a story seem too neat or formulaic. Sometimes, as alluded to earlier in this review, this openness worked brilliantly, but on other occasions I would have appreciated just a little more hand-holding. “The Cresting Water,” one of the longer pieces in the collection, ends with a last-minute twist that seems to upend what the reader has been led to believe, but the minimal justification given for this left me feeling confused. At other times, the balance seems tilted a little too far in favor of neatness. The ending of “The Potluck”– a story clearly indebted to Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” – suggests small-town life continuing as normal after a horrific event, which its participants know will have to be repeated, but there is something too convenient about the way this is summarized, especially given that the story is narrated by one of the participants who admits to having “devised plans to escape.“ Yet writing fiction of this length–some are flash, some a little longer, though none of them very long–always involves making fine judgments about “completeness” within tight constraints, so it must be to this author’s credit that so few pieces here felt incomplete.

This is an engaging, sharply observed collection dealing with womanhood and masculinity, grief and recovery, voice and silence. If you are looking for smartly written, inventive stories that find time to be playful and serious, then I heartily recommend.

Want to learn more about Jennifer Fliss’s work? Check out our interview with her.