A Review of Vivienne by Emmalea Russo

Words By Ainsley Louie-Suntjens

This title was published on September 10, 2024 by Arcade Publishing.

*SPOILER ALERT* This review contains plot details of Vivienne.

Vivienne sort of fell into my lap, and I am so happy it did. I love a debut fiction novel written by a poet, partially because I am also a poet working on a novel, and because I know even if I don’t enjoy the story, it will always give me food for thought. I am delighted to report the latter was not true: this novel checked nearly all my boxes—it felt almost written for me. It was strange, artistic, lyrical, experimental; most of all, it was full of weird, memorable women, which as I’ve mentioned before, is one of my favorite topics in the world to read about.

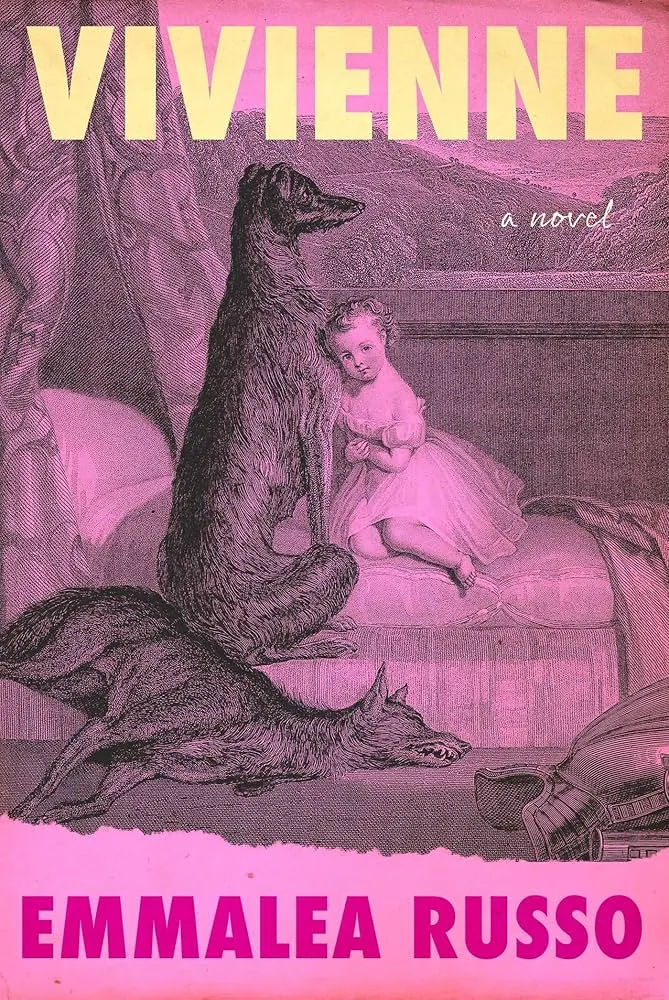

Vivienne is a novel that primarily tells the story of three generations of women. The first and the namesake, Vivienne Volker, is an artist who creates surrealist clothing, lover to Hans Bellmer, and the maybe-murderer of Wilma Lang. Did she murder Wilma Lang? Who knows. Wilma could have fallen out of that window on her own, and as Vivienne puts it, was of weak temperament. By and large, the novel doesn’t want to give the reader an answer, and seems to ask instead: does it matter—would it color your perception of her work? Secondly, is Velour Bellmer, Vivienne’s long-suffering daughter and foremost scholar on her work, who lives in a tatty, white bathrobe and spends long hours making photo slideshows of her mother’s clothing, which she posts to YouTube. The last is Vesta Furio, Velour’s seven-year-old daughter, Vivienne’s granddaughter and devoted acolyte. She dresses like her grandmother, speaks like her grandmother, watches Ingmar Bergmann films with her grandmother, and follows her to and from Mass—pausing only to baby the massive family greyhound, Franz Kline. The only nonfemale and nonVolker perspective the novel explores is that of Lars, the owner of a gallery preparing to display Vivienne’s first exhibition in several years. Lars stands in powerful contrast to the Volker women; he is vulgar, pretentious, and overwhelmingly creepy, particularly towards Vesta. These perspectives converge in the days before the exhibition debuts, and all the creepy, sculptural baggage the display brings with it.

The plot is almost secondary in Vivienne—it’s important and it keeps the story chugging along its trajectory, but the real treat was the language and structure. You can tell Russo is a poet. She refuses to play by the rules of the novel; it is part prose, part poetry, part internet forum. Time speeds up and slows down. We float between perspectives seamlessly and skip from prose poem to group chat in a moment’s breath. The best part is it felt effortless; not once did it feel like experimentalism for the sake of it, or like Russo was shoehorning in a format change to be different. All the hybrid moments had purpose, from the “comment sections” creating the blathering cacophony of opinions on Vivienne, to the prose-poetry illustrating Vivienne’s slippery memories of the moments leading up to Wilma Lang falling (or shove) out of that window.

One character I have not seen extolled nearly enough was Velour. I love that tired, irritated woman—trapped in the shadow of her mother holding hands with her daughter, yet somehow content to stay there. Velour, the fabric, is imitation velvet; Velour, the woman, is imitation Vivienne, dressed in terrycloth white to her mother’s, and daughter’s, black shrouds. Always the art critic and never the artist, but too tired to resist anymore. She’ll settle for having sex with her mother’s boyfriend under the grotesque supervision of The Machine-Gunneress In A State of Grace, and eventually selling Vivienne’s comatose body to a biotechnology startup.

Which leads me to my biggest question: the ending. To summarize, at the opening of the exhibit, an angry onlooker throws a brick through the front window of the gallery, which hits Vivienne in the head and puts her into a coma. Vivienne remains comatose for years, until Velour sells her body to a biotechnology startup to be used as a human incubator. The startup aims to breed more artists. This is the point of the novel where I wondered if we were veering too far into the surrealism. I understood the purpose—the gutting of the artist’s humanity in the name of commercial reproduction and capitalist profit—but I wonder if there’s a way this could be explored that didn’t feel so disjointed. I feel this could be achieved with Vesta and Lars in some way. Their relationship made my skin crawl, and I wonder if that effect could be exploited further. I know this may be a stretch but make Lars grosser. Emphasize Vesta’s artistic inclinations more; maybe invoke Vivienne. For me, the icky relationship between them was the clearest representation of exploitation of the artist by capitalist profit: Vesta is a would-be artist, groomed by a pedophilic, disgusting gallery owner.

This ending felt almost sci-fi in its tone, when up to that point, Vivienne was a family drama exploring the nature of art and its consumption. At the last moment, it introduced the larger worldbuilding element of this startup when the novel was largely contained to the Volker household, the gallery, and the three Volker women. It left me questioning and drew focus from the book’s core strengths, its commentary. In some ways, this works; it is incredibly jarring and there is a sudden loss of warmth and charm, but it also left me feeling unsatisfied. There was an experimentalism that was intriguing, but I could not find a solid conclusion to the experiment.

Vivienne is a book about artists, their art, and those who discuss and criticize and obsess over their art. It is about women—as humans, as creators, as mothers, as daughters—and how it all bumps and grinds up against one another. It is about capitalism, and how it needs the art but hates the artist. It is surreal, disorienting, and often stunning. It is sometimes disgusting, often depressing, more often than not both at once—but not always. That is the treat of Vivienne. It is never just one quality, one moment, one voice. It’s like one of Vivienne’s impossible garments; defamiliarized, deformed, and then disintegrating in your hands.