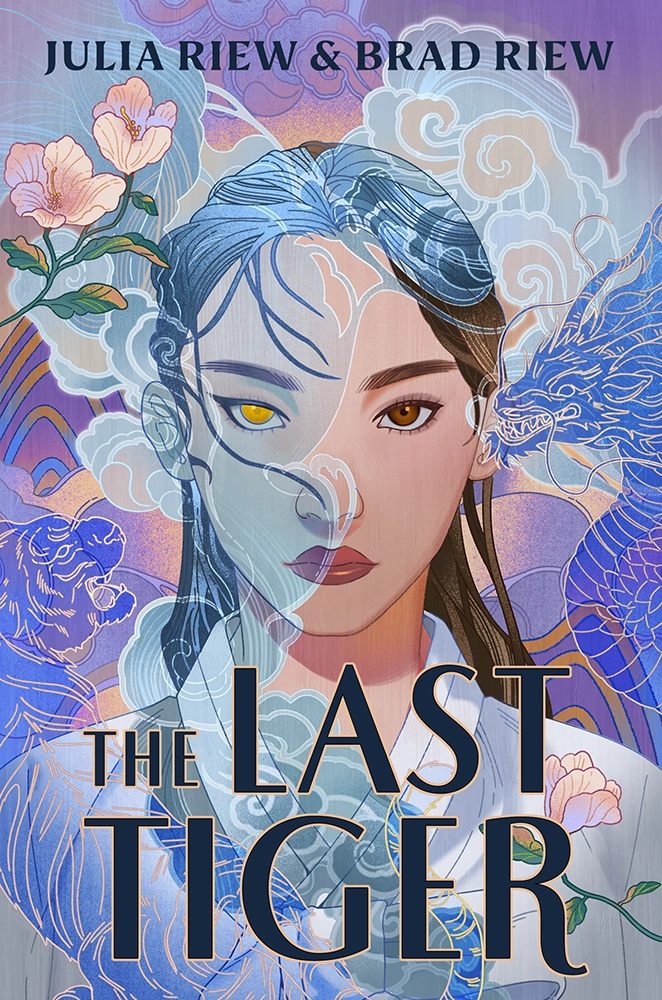

A Review of The Last Tiger By Julia and Brad Riew

Words By Melissa Paulsen

This title was released on July 29, 2025 by Kokila Books.

*SPOILER ALERT* This review contains plot details of The Last Tiger.

“If we forget who we are, then we can be controlled … Then let’s not forget. Let’s make them remember.”

Sibling writing duo Julia and Brad Riew’s debut YA fantasy novel, The Last Tiger, explores their grandparents’ harrowing experiences of living under Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea during the 1940s. Featuring quotes from their grandparents at the start of every chapter, The Last Tiger is more than a tale of survival; it’s a story of two people from opposite worlds overcoming hardship and forbidden romance to change their destiny amidst an empire seeking to eradicate them.

For years, the people of the Tiger Colonies have suffered under the colonial occupation of the Dragon Empire. They must ration their food and harvest minerals in the coal mines to add to the militaristic Dragon Empire’s prosperity, knowing they’ll face severe punishment if they dare to fight for their homeland. Drained of their resources and politically powerless, the citizens of the Tiger Colonies watch helplessly as their culture gets erased, starting with the death of the revered tigers that once occupied the land, until only one remains.

One night, Lee Seung, a sixteen-year-old servant boy, catches Choi Eunji, the youngest daughter of one of the elite families in the Tiger Colonies, sneaking out of her family’s compound. To keep her secret, Eunji promises to tutor Seung for the Exam—his one shot at a successful and stable future. In return, Seung introduces Eunji to a vivacious world outside of her family’s estate. The two quickly develop feelings for one another before they are separated by unforeseen circumstances. A year later, Seung and Eunji find themselves on opposite sides in the battle for the last tiger as Eunji trains in the Dragon Empire’s renowned Adachi Academy and Seung toils in the Tiger Colony coal mines.

The worldbuilding in The Last Tiger is incredible, blending a thoughtful magic system, references to Korean and Japanese culture, and vivid imagery. Enabling the Dragon Empire’s conquest of the Tiger Colonies is a magical force called “ki,” which takes three different forms based on its kingdoms of origin. Dragon ki grants the Empire soldiers unmatched strength and endurance. The warring Serpent Queendom’s Serpent ki gives the power of mind control. While the long-dormant Tiger ki focuses on the power of human emotion. Each of these forces has clear limits and balances each other out, leading to conflict between the characters and adding to the broader wartime narrative. The Riew’s also include several nods to Korean and Japanese culture through clothing like hanboks and kimonos, food like tteokbokki (rice cakes), and mythology with revered tiger and dragon spirits.

In addition to their worldbuilding, Julia and Brad Riew do an excellent job of crafting well-rounded characters suffering under colonialism. Seung portrays the struggles and rage of living in a political system designed to keep him oppressed, “Everything about the colonial society the empire has built for us—it’s all intended to keep us hoping, striving for a better life, but never quite able to achieve it.” Whereas Eunji offers an intriguing perspective of the “yangban” or Tiger Colony citizens active collaboration with the Dragon Empire to survive. Eunji eventually learns her family’s prosperity is the result of the Tiger people’s losses. Despite her wealth, she’s equally as trapped as Seung due to her gender being perceived as inferior and facing a corrupt system.

Even the side characters are well-developed and offer diverse perspectives, especially Kenzo Kobayashi and Jin. As the military prodigy of the Dragon Empire and Eunji’s arranged husband, Kenzo is a foil to Seung and an antihero with a dark secret. Where Seung is a quiet, attentive listener, Kenzo is the guy who knows “the world was built to serve boys like [him].” But when he accompanies Eunji on her quest to capture the last tiger as her “protector,” he’s exposed as a fraud when he can’t use Dragon ki in battle. Kenzo acts in his own interest to survive, betraying Eunji and Seung by turning them over to the malicious General Isao. Yet, he ultimately helps Seung and Eunji escape, revealing his morality and love for Eunji.

Jin, a Tiger Colony rebel with powerful Serpent Ki, exemplifies how “hurt people, hurt people” in her all-consuming desire for revenge against the Dragon Empire. When she was fourteen-year-old, she was tricked into sexually performing as a “comfort woman” for the Dragon soldiers. Since then, she’s been “so consumed with pain that she can no longer see the humanity” in the Dragon Empire citizens and almost kills Eunji and Kenzo. The emotional baggage of Jin’s dangerous past prompts her to teach Seung, “[Anger] is the most powerful fuel [he’ll] ever have,” and illustrates how victims of trauma may repeat harmful behaviors toward others.

Although intended for middle-grade readers, The Last Tiger’s consistent tension makes for an action-packed read for all ages while also tactfully approaching the mature themes of cultural assimilation, grief, sexism, and socioeconomics. Perhaps because the novel is intended for a younger audience, I found the authors’ voice juvenile at times with simple sentence structures and an over-explanatory tone that told was happening instead of letting readers infer for themselves. For example, Seung doesn’t like Kenzo, but instead of seeing this through his actions or dialogue, he thinks, “If I’m honest, I just don’t like him. He’s entitled, beyond arrogant, seeping with self-loathing.”

Additionally, the inclusion of an over-explanatory epilogue felt unnecessary. In the final chapter, Seung and Eunji reawaken hope, “something that can no longer be stopped,” in the Tiger People through forbidden song. The song unites the Tiger People by reminding them of their collective culture and empowers them to take a stand against the Dragon Empire.

The epilogue had a “happily-ever-after” framework which felt like a letdown after all the challenges these characters endured to save their country, and it made the final chapter less impactful. I would’ve preferred to see more snapshots of Seung and Eunji’s newly restored relationship in the nascent “Tiger Republic” than a fairytale-like “perfect” ending.

Overall, I loved getting swept into the epic fantasy world of The Last Tiger and its compelling message of hope, love, and resilience. Knowing this story was rooted in the tragedy of the Japanese occupation of Korea, and that Seung and Eunji were based on real people, added to the levels of authenticity and raw emotion prevalent throughout the narrative. The Last Tiger is perfect for fans of Mulan and other modern retellings of East Asian mythology, like Where the Mountain Meets the Moon by Grace Lin and Song of Silver, Flame Like Night by Amélie Wen Zhao.