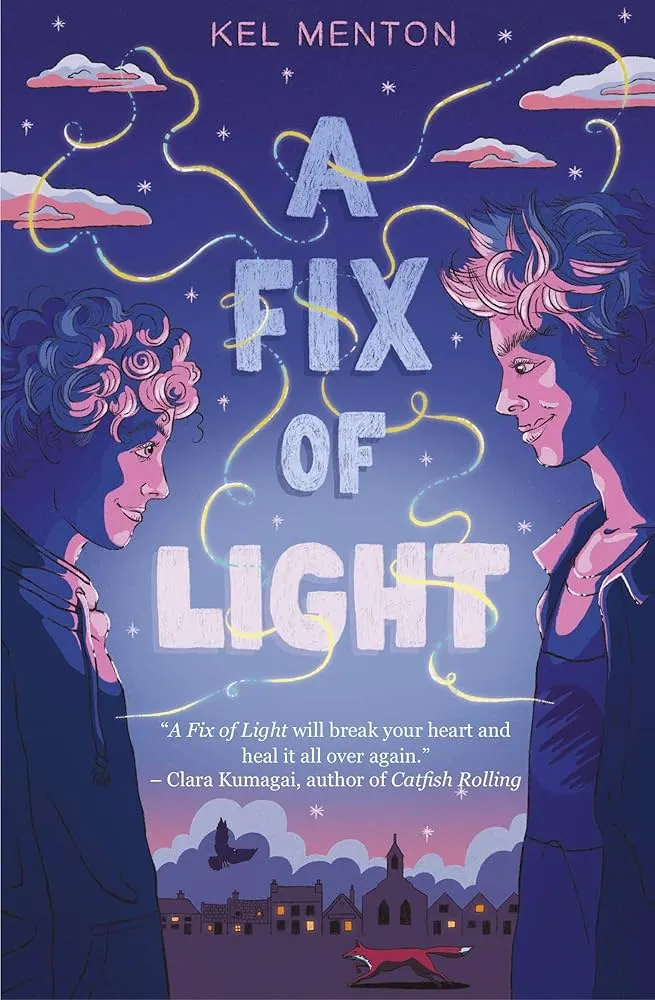

An Interview with Kel Menton

Words By Kel Menton, Interviewed by Beatrice Basa

While A Fix of Light is your debut novel, you’ve put your work out before as a playwright, poet, and short story author. What made you settle on a novel for Pax and Hanan’s story?

The novel was my first love. I wrote a few novel-length stories in my teens and didn’t try out poetry or playwriting until later.

So much of A Fix of Light takes place inside its characters’ heads. Their thoughts, feelings, reactions, and relationships are precisely what I wanted to put under the microscope. The novel let me explore all these nonverbal experiences and give them all space to breathe.

A Fix of Light’s fantastical aspects are clearly and deeply ingrained in Irish folklore, but were there any particular myths that influenced your story? Do you have a personal favorite?

I was actually researching Irish wolves when I came across legends like the werewolves of Ossory. I wrote a play, Sióg, about the last wolf in Ireland, and the story stayed with me. By that point I’d already started working on A Fix of Light, and the magic in Sióg just seemed to fit. If we had shape-shifting wolves, why not foxes?

The Good Folk have been a constant presence in my life, thanks to stories passed down from my grandparents. I love anecdotal stories best; the ones that older people tell, about being a young child and hearing music in the twilight, knowing that the Folk were singing in the garden.

Your story is set in Skenashogue, a town near your home of county Cork. What made you decide to set A Fix of Light so close to home? Any other areas you’d be interested in exploring?

It’s so uninspired, right? A Corkonian who loves Cork. In other news, the sky is blue, and water is wet.

Skenashogue isn’t just Cork, it’s the Cork in my childhood memories. I wanted the idyllic summer backdrop to contrast against the angst I was feeling (and injecting into poor Hanan and Pax). To me, idyll was West Cork beaches, montbretia, and animals in faraway fields.

I imagine I’ll come back to Ireland, maybe even Cork, as a setting in the future. I can’t share details yet, but the thing I’m working on now is set in a fictional city-state between Germany and the Netherlands. I am nothing if not inconsistent!

You’ve been open about how much of A Fix of Light draws upon personal teenage experiences. Was writing it challenging and/or therapeutic at times? How did you find balancing its darker themes with hopefulness?

It was challenging at times. I wanted the emotional truth of things to be authentic, but I also wanted to protect myself. It forced me to be honest about my feelings, which I wasn’t good at, but once I’d extracted that raw material, it was a little easier to craft into something that put some distance between me and the story.

Until I’d experienced genuine hopefulness myself, I struggled to finish the book. I didn’t want to give Hanan and Pax a fairytale ending, because that seemed dishonest. At the same time, dooming them to a tragedy made me feel ill. If I condemned some of my oldest friends to a terrible life, what did that mean for me?

When I learned a little more about hope, I was able to imagine it better for the boys. I wanted to leave the reader with a tangible sense of attainable hope, so they could say, “This is something I can have, too.”

You mention you got your MA in medieval literature, focusing on the concept of monstrous Other. How have your studies influenced your exploration of queer identity and neurodivergence?

I took a module in undergrad all about monster theory, and so much of my Self finally made more sense. I’ve felt Other and monstrous my whole life, and it’s become a bit of a badge of honor, rather than something to be ashamed of. I cannot, now, untangle my queerness from my autism from my monstrosity. After all, the “Other” is a necessary part of the ecosystem.

Of course, I can only speak to my own queer identity and autism; “Othering” continues to be a tool of oppression, and I don’t want to presume that anyone is comfortable with the label.

The publishing process can often feel more stressful than the actual writing. What is something you wish you’d known before?

I took rejections on the chin for a long time, because all my favorite authors had been rejected and still succeeded. When weeks turned to months turned to a year on submission, though, I began to worry that my confidence in my work was actually arrogance, and I was No Good, and I should give up now.

Instead of spiraling, I should’ve reached out for support—from my friends, agency siblings, and my agent, all of whom immediately rushed to buoy me and restore a bit of my hope.

You will have to be patient. You will have to work hard to keep your hope alive. But you don’t have to do these things alone.

While the literary world today is more vibrant than ever before, there is still work needed in uplifting marginalized voices. Any words of wisdom you’d give to young queer and neurodivergent writers about being in the literary industry?

I don’t know that I am wise, yet, though I have a few things to say, which are hopefully wise-adjacent, at least.

1. Community is vital. You have to figure out what that looks like for you but connecting with people will make you all stronger. You do not have to do this by yourself.

2. Don’t forget to protect yourself. You can be open about being queer or neurodivergent without baring your soul. It’s not dishonest to keep some parts of yourself just for you. 3. Leave the door open behind you. There is enough success to go around.