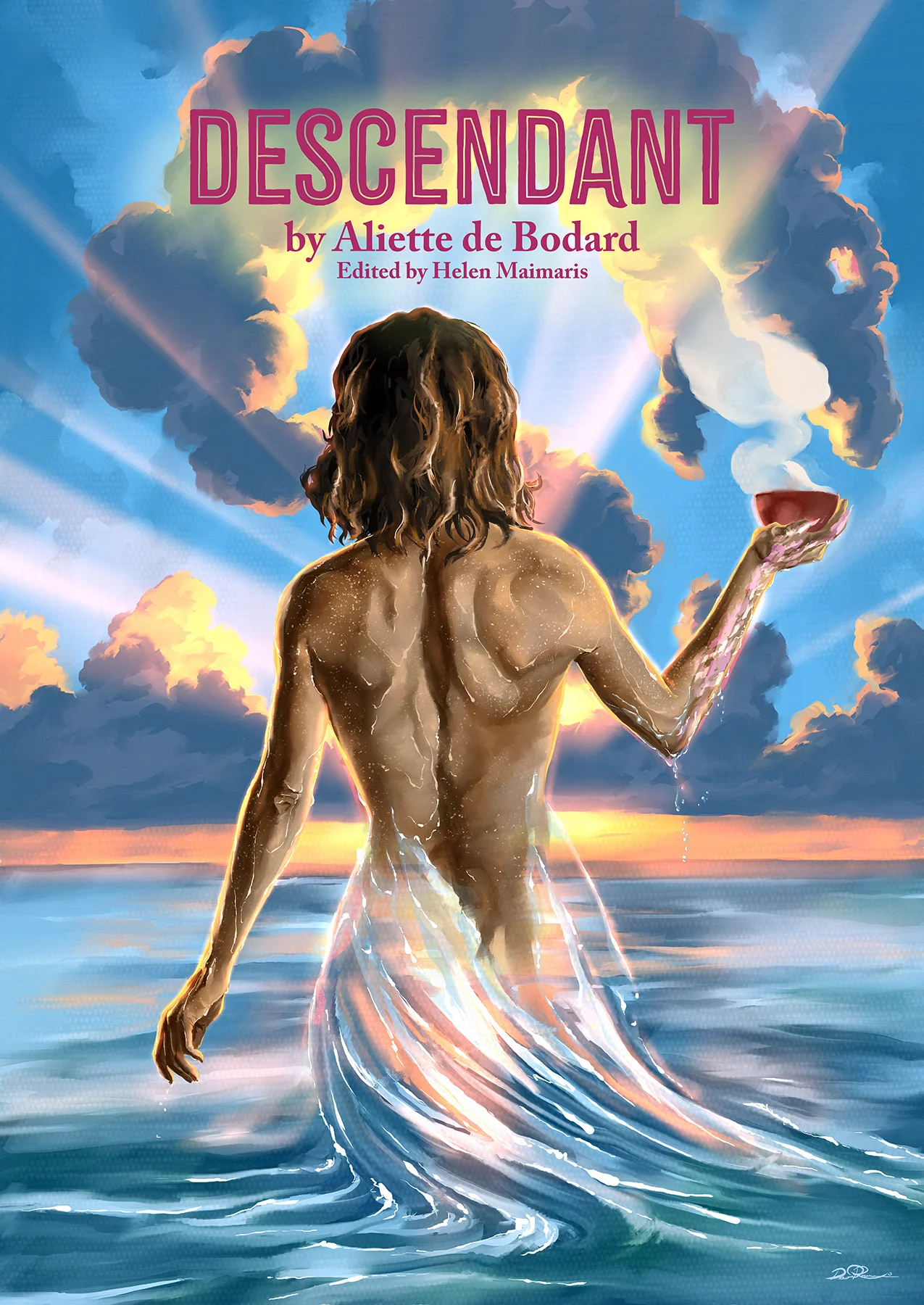

Descendant

Words By Aliette de Bodard, Art By Daniel Reneau

Of course, Lâm got the nighttime shift again. The one shift she thoroughly hated. Neither her coworkers nor her supervisor understood why. Surely it was the quietest time, with the fewest arrivals of Descendants, the least paperwork and processing?

Of course, Lâm had never started on the Path herself. Her Call was old and kept pulling at her, but unlike the Descendants, she had never heeded it. This created a situation that Lâm had not seen with any of the Descendants she met at work: her Call seemed to be completely invisible. At best, her coworkers thought she hated night shifts because of Minh, who was usually running security at that time and whose relationship with Lâm could best be described as tense.

But it wasn’t about Minh (who was, truth to tell, a rigid and sanctimonious idiot).

The trouble was that there was nothing to do at nighttime. Once Lâm was done with rearranging the layout of the reception desk, with cleaning the teaware five times, and making sure everything was in its proper place for the breakfast buffet (it nearly always was, because the evening team had done their jobs), once she was done with all these avoidance tasks, with all the minutiae of small things she could do to stave it off, once she was sitting at reception, staring at the screensaver on the computer, at the slow dance of the Path Company’s logo moving like algae waving in some invisible current…

…Once she was done, the visions of the Call always came.

It always started small: something on the edge of her field of vision, a shimmering, a faint wavering of the paintings in the reception lobby. The backs of her hands itching. A barely perceptible smell of brine, and the sound of the wind slowly and steadily rising, covering the noise of the computer’s fan, the motor of the vending machine, her own frantic heartbeat.

Slow and steady, and never stopping.

Then the odd, uncomfortable feeling of her skin tightening, too small to hold in the whole of her unfurling self—a desperate need to scratch it all off, to finally breathe, in all her power and glory.

By that time, the whole of the reception lobby was usually overlaid with a faint pattern of waves, and Lâm would hear the crash of the ocean in her ears. And then she’d look down and see her hands—the shimmering imprint of scales beneath her skin, the lengthened fingers ending in claws. And it would feel so easy, so tempting to just go towards the waiting Path, to travel its length to its end at the nearest harbor.

Someone was screaming. Something touched her shoulder and it was viscous algae, and she jerked away, and she—

“Excuse me?”

It wasn’t algae. And the person wasn’t screaming, but talking. It was a guest.

Lâm looked up, blinking to clear away the undersea landscape. A hazy silhouette stubbornly refused to come into focus. Her eyes had adapted to undersea sight and didn’t want to return to normal. This had happened before. She was going to be all right, once it cleared. She was going to be all right. All she had to do was her job.

“Yes?” she said. Her voice felt faraway, booming and too large for the lobby. It was unfair, grossly unfair. She hadn’t asked for any of this.

She had found over the last three years that working in a Descendant hotel made resisting the Call easier for some reason. It wasn’t her favorite job: when she worked the night shift, it meant she couldn’t join her housemates for dinner. Nga would make sure she had food left in the fridge—she really behaved like a full-on auntie, mothering Lâm even though she was a year younger. And after night shifts, Lâm usually arrived back home before Công left for her office job, which meant they could catch up over a shared meal—Lâm’s late dinner and Công’s breakfast—discussing the latest books they’d read and the incongruous things they’d both seen on their way through the city, which Công so loved to sketch.

“I’m really sorry, nothing else was working to get your attention.” The voice was female, older than her. “I really do need the room.”

Reflex kicked in. A late arrival. Despite the apology, the guest didn’t sound sorry. There was a faint iridescence to her skin and eyes, which meant she was already some way along the Path and used to the way the Company eased her passage as she slowly made the journey toward the nearest harbor, toward the sea that would become her home.

Lâm tried hard, very hard, not to think of her mother’s own Path, of the tautness in her emaciated face toward the end, of the sheer relief when she and twelve-year-old Lâm had finally reached the harbor after weeks of travel.

Of the way the sea had risen to meet her mother as she waded in—a whirling of ribbons of water spreading out from her and the shadows of dragons gathered in the open sea, calling her onward.

Mother hadn’t looked back or expressed regret. Not once. The Call had erased all that from her—even the desire for land food or drink. Even love for her own child. No, she hadn’t looked back, and Lâm had been left behind, trying to move on. But how did one move on from that?

Nga, drunk at night, often got blasphemous and said that Mother had failed parenthood, and she didn’t deserve to be worshipped or remembered. Lâm would shake her head and say it wasn’t that easy and the argument would end over a plate of mung bean cakes with nothing solved—neither Nga’s bitterness at the way parents sometimes behaved nor Lâm’s resentment and loss. Công simply shook her head and said that sometimes people were weird, and that didn’t help either.

Lâm hadn’t told either of them about her own Call. It was too hard, too personal, too fraught. She didn’t want their friendship to sour or end, the way it was bound to if they had that conversation. Descendants weren’t meant to have attachments or friends once the Call came; everyone knew that Descendants would be inexorably drawn into the sea.

Descendants. Con Rồng. Children of the Dragon. Called to the sea. Blessed, the Company said. Except that, of course, it was everyone else who picked up the pieces and everyone else who had to deal with the consequences of such barbed blessings.

“I’ll need you to fill this in,” Lâm said, sliding a sheet of paper in front of the guest. “And ID and a card, please.”

The guest frowned. She looked a bit like an older Công, all harshness and sharp observations. “A card?”

“A credit card. For incidentals.” Lâm made her most practiced apologetic face. “The Company covers meals and accommodation on your journey, but you may want extra things. Mini bar. Room service.”

The guest studied the registration form as if it had personally offended her. Lâm studied the ID on the desk. Nguyễn Thị Nguyệt Uyển, a traditional and old-fashioned name. Place of birth was in the western provinces, a long way from Azure Sky Hotel. She was near the end of her Path. But asking about her Path would be too personal, too intimate, and Lâm didn’t want that sharp gaze turned on her. So instead, she slid the card and the ID back and proceeded with the registration.

“Here you go,” she said. “Your room number is written on the leaflet and the lifts are this way. Breakfast is at 10 a.m. and here are your access codes for the Path app. It interfaces with the guidance system on your phone’s maps, so you’ll know where to go next.” Not that she’d need it—as Lâm herself was ample proof, the Call was relentless, as unerring in its accuracy as the instinct of migratory birds. Descendants never got lost. They went where they were supposed to, all of them.

All except middle-aged, stubborn, selfish, scared Lâm.

Lâm expected not to see Nguyệt Uyển again. Her shift ended early in the morning, before the breakfast room was opened. And she was exhausted. Lately, night shifts left her feeling that way, like she’d run a marathon and never stopped. She’d come home and collapse, barely able to talk to Công or enjoy Nga’s food.

But when she emerged from yet another bout of visions and hallucinations and went to the tea rooms to boil water for a grounding drink, she saw that Nguyệt Uyển was sitting cross-legged in front of the table furthest from the kitchens. She’d gotten herself one of the complimentary tea sets, and she was staring at the delicate blue porcelain cup in front of her. Lâm couldn’t see her expression. From the back, she looked so much like Mother that Lâm felt a stab in her chest, an icy twist around her heart.

Don’t do it, Nga would have said. It’s not worth it.

She’s not Mother, Công would have pointed out. But Lâm was neither of them.

Before she knew what she was doing, she was walking toward the table. It was highly improper to bother a guest, but what propelled her was even harder to resist. “Are you all right?” she asked. “You should get some sleep. It’s a long journey.”

Nguyệt Uyển looked up, her distant gaze returning to focus on Lâm. The faint scattering of scales on her cheeks disappeared. “That’s very kind of you—” she stopped, leaving an all- too-obvious space.

“I’m Lâm.”

“Would you care to join me?” Nguyệt Uyển gestured towards the tea.

Lâm hesitated. She wanted to go home. She wanted to sit with Công at breakfast and discuss Nguyệt Uyển the way they discussed that odd man on the bus, or the child disguised as an ornate lion dancer near the noodle shop. Odd, amusing, the subject of distraction and laughter. Distant. Safe.

“It’s late at night,” Nguyệt Uyển said, “and it’s not like there’s much to do. Or would you rather remain alone with your Call?”

Lâm had not expected that. Not—not that. No one was supposed to see her Call. “How—how do you know?”

A smile from Nguyệt Uyển. “It’s my job. Or used to be.” There was an odd inflection in her voice: half-regret, half-anger. “Marine theologist. I studied dragons and Descendants.” She snorted, genteel and careful. “Somewhat ironic that I’d end up being Called. But anyway, it’s hard to miss the look of the Called. You’ve got it and you’ve got it bad.”

It was all too much, all too casual, all too probing. Lâm sat down, overwhelmed, watching Nguyệt Uyển pouring tea in a practiced gesture. The smell of jasmine and cut grass wafted up to Lâm. “You don’t sound very concerned about being Called.”

“Concerned?” Nguyệt Uyển stared at her tea. “I suppose I’m not.”

It was Mother all over again, wasn’t it? A wound that could never close no matter how much therapy Lâm tried on it. And yet… perversely, she found herself envying Nguyệt Uyển’s serenity. She seemed utterly unperturbed by the effects of the Call. “Have you no family?”

“I do. My husband was Called a few years back, and our daughters are grown now. You?”

“No,” Lâm said. She’d had a few girlfriends, but the Call made it hard. By daylight, it was sort of manageable, but few relationships could endure night after night of nightmares that would leave her gasping and struggling to distinguish between vision and reality. But she had Nga and Công, her little community of people where she belonged. Those who looked after her as she looked after them. “It’s all right, really. I’m not lonely.”

A sharp look, but Nguyệt Uyển said nothing. Instead, she poured them both more tea. “I made my goodbyes to my daughters, but it’s not like I’m going very far.”

“Dragons don’t come back.” Lâm’s voice was harsher than she meant it to be.

“Hmm.” Nguyệt Uyển sipped at her tea. “That’s not quite true and you know it. Get a boat and go out to sea, and they’ll come.”

She’d tried that once, when she was twenty. A small boat hired with Nga and Công, the movement making her seasick; the wind buffeting her as she stood on the deck, the smell of the sea everywhere, swallowing up Nga’s angry words and Công’s observations. Then, silence. And dragons. Dark silhouettes seen underwater and then by the side of the boat, staring up at them as the wind died down.

“Yeah,” Lâm said. “They do. But they’re not the same.” They’d all looked alike, and whatever language they spoke had made no sense to Lâm. One of them had come closer, staring at her, antlers shining with sea salt, droplets of water scattered in their iridescent mane. She’d called Mother’s name but they hadn’t answered, just remained there staring at her with the open sea between them. But then the other dragons had called out, and they’d turned and dived back into the water, blessing delivered, storm quelled, nothing more.

Nguyệt Uyển’s gaze was sharp and compassionate. She didn’t ask who Lâm had lost. Instead she said, “The Call runs in families. Not always, but often. So it wasn’t exactly a surprise for me.”

Lâm said, before she could stop herself, “Is that what happens, when you walk the Path? You just… stop caring?”

“About what?”

“Everything. People. The family you leave behind. The things of the world. Just—” The pleasant warmth of the sun on cobblestones; the small terraces with tea and dumplings, Nga’s and Công’s laughter wafting in the evening breeze; the sharp, acrid taste of the first tea in the morning, looking at sketches alongside Công.

A silence. Nguyệt Uyển was breathing in the tea, slowly, deliberately. “Everything you lose…” she said. “Drink your tea,” she added, not unkindly. “I’d like to ask you a question. You don’t have to answer. Though I’m older than you and a guest, and I measure the respect and obeisance you think you owe me, I’m not here to pry. At least not unduly. How long ago did they leave you for the sea?”

Lâm was silent for a while. She’d not told anyone on the staff. But there was no one else she could talk to in this way, and it felt like a burden she’d borne for too long. “I was twelve,” she said. She stared at her hands, half- expecting to find the imprint of scales on them again. “I don’t know how I’m meant to deal with that.”

“The same way we deal with everything,” Nguyệt Uyển said. “The best that we can with what we currently have.” She sighed. “You say I’m not concerned. I am. I’m angry that I have to leave everything behind. I’m sad that I won’t get to see either of my daughters marry or have children or be there for the rest of their lives. I’m scared of what it’s really like, to be in the sea. And I have regrets. Of course I do. But it’s not like I have much of a choice.”

“And so you just… give in?”

A shrug. “I’ve learned to accept it. It’s what the Path is, isn’t it? Why the Company exists. Not for accommodation and meals, though I guess that’s part of it. But with each stop—” Another shrug, a touch of rainbow light in her eyes, reminiscent of the dragon’s gaze on Lâm all those years ago. She could hear the roaring of the wind in her ears. “With each stop, one gradually yields to the inevitable. As I said, I’ve made my goodbyes.”

“I refuse.” The words were out of Lâm’s mouth before she could stop them. There was too much bitterness bound up in all this. “I have people here. I won’t leave them.”

“That’s good, I guess.” Nguyệt Uyển didn’t sound convinced.

“Are you mocking me?”

“I’m not.” Lâm saw that there was pity in her eyes and that felt even worse. “You said you were all right. I’m glad you are.” She set her cup back on the table and looked up, behind Lâm. “I think your colleague is looking for you.”

Lâm turned. Minh was there, his face flushed—by his expression, something had gone wrong, and he needed Lâm’s softer touch to untangle whatever messy situation a guest had come up with. “You’re right,” Lâm said. “I have to go. Thank you for the tea. And you really should get some sleep.”

Nguyệt Uyển inclined her head. Her gaze was distant once more. “May we meet again,” she said.

May we not, Lâm thought, but she was rattled enough that she couldn’t get the words out of her mouth.

Lâm finished her shift with no further incidents. She rode the bus all the way back to her flat more exhausted than she’d ever been, the visions of the Call superimposing the darkness of the depths atop the shops and the streets.

At home, Công was waiting for her. “Hey,” she said. “There’s shrimp soup in the oven. Nga left it to warm before she went to work.” She was sipping a bowl of congee with salted eggs. “How was your night?”

Lâm found herself at a loss for words. Behind Công, she could see algae clinging to the kitchen cupboards and the sound of the wind was almost drowning out what Công was saying. “Not bad,” she said, automatically. “How was your day?”

“Interesting,” Công said. “I found a little temple on the Fifth Avenue, near the Azure Gardens. Had no idea it was there. Look.” She opened her sketchbook. All Lâm saw was waves and dark shapes, and instead of Công’s enthusiastic descriptions of worshippers, all she heard was the whistling sound of the wind and the thunder of the distant sea.

“I’m sorry,” she said finally. “I’m exhausted. Can we talk later? When I’ve had sleep.”

Công’s face darkened. She opened her mouth, said something—and when Lâm didn’t react, reached out to touch her shoulder. The visions died away. “They work you too hard. You know that? You’ve barely gone out in months. You always say you’re tired. Can’t you just say no to them?”

“Please.”

“All right,” Công said. She swallowed the last of her congee and closed her sketchbook. “I’m off to work. I’ll see you tonight?”

“Of course,” Lâm said, and it felt bitter on her tongue, as if she was lying.

After Công had left, Lâm retrieved the soup from the oven but found she wasn’t hungry. Maybe something else?

She brewed herself a last tea before bed. It was jasmine green, the same tea Nguyệt Uyển had made. She stood in the silent kitchen for a while, breathing in the smell of jasmine and grass. The visions were gone, for now, and her skin was her own, if a little too pale from lack of sun. She should go to the botanical gardens on her next day off.

Except… when had she last been able to go out for more than work?

She stared around the room. A small kitchen with an impeccable counter. Bookshelves. Flowers.

A routine. Colleagues she didn’t confide in. Friends she hid her Call from. No, worse. Friends she couldn’t even properly hear anymore.

How long had it been since she’d been able to have a conversation with Nga or Công? The Call had started to overlay everything a while ago. A long, long while ago, if she was honest with herself.

Have you no family?

You said you were all right. I’m glad you are. She lifted the teacup. She wanted to cry and she wasn’t sure why. She paused, the teacup at her lips.

Nguyệt Uyển.

Echoes of their conversation, of the ease with which it had happened, how she’d opened up in response to Nguyệt Uyển’s own confidences. A sudden, sharp, wounding realization, like a blade in her innards.

She’d had more connection to a lone stranger than she’d had with anyone in years.

She felt her hand start to shake.

She had Nga. She had Công. But… but every moment with them, she wasn’t telling the truth. Every moment with them, the Call encroached.

It would always be there.

Lâm thought of Nguyệt Uyển serenely pouring tea. Of all the other Descendants on their Paths, going hotel to hotel until they reached the sea and the dragons came to welcome them. Of Mother’s sigh of relief when she’d finally reached the water.

She drank the tea. As it left a trail of warmth down her throat, she felt understanding shift within her. She could wait and wait until the Call hollowed her out, keep living this half-life. Or she could go, abandoning her housemates as Mother had once abandoned her. She could keep on resisting until the bitter end—but what would be left of her, if she did?

It wasn’t that Mother hadn’t loved or cared for her. She had, as much as Lâm cared about Nga and Công. More, even. But, she thought, some things just were, like the calm at the end of a storm or the foam as a wave crashed on the sand. They happened, and the only freedom was what dignity to behave with and what kindness to extend to others. Neither Nga nor Công deserved to share the half-life Lâm was living, the constant exhaustion that no longer allowed for joy or true moments of community.

The Call was trembling at the edge of her thoughts—visions waiting to take over once more. She breathed in, and felt not serenity, not calm, but something like a weight settling on her. An acknowledgement of who she was. Of whom she was meant to be.

Descendant. Child of the dragon.

I’m scared, Lâm thought, and she felt like she was twelve again, watching Mother immerse herself in the harbor’s waters, watching her change. She was twenty, staring at the dragon over the prow of the ship, the moment trembling in the air. She was thirty-seven and watching the iridescent light playing in Nguyệt Uyển’s eyes.

Her hands shook again, unsteady. The tea shivered in her grasp.

She swallowed her mouthful and set the cup back on the counter, staring, for a brief moment, into its trembling depths. Then, before she could change her mind, she began writing a letter to Nga and Công, keeping it brief and factual, until she was ready to sign off.

I care about you deeply. I love you and I miss you already, but I have to go.

She left it on the table next to Nga’s cold soup and Công’s empty bowl of congee, where neither of them could miss it. They would be angry or sad; they would seethe at her lie and her lack of goodbyes in person, or weep for her or miss her. Or perhaps all of these.

But the wind was rushing once more, scales forming across the backs of her hands, waves rising up in front of her.

Lâm walked away, through the door, toward the streets lit by the rising sun, toward the hotels and the distant harbor, and, eventually, the fated sea.