An Interview with Lucy Sullivan

Words By Lucy Sullivan, Interview by Lydia Layton

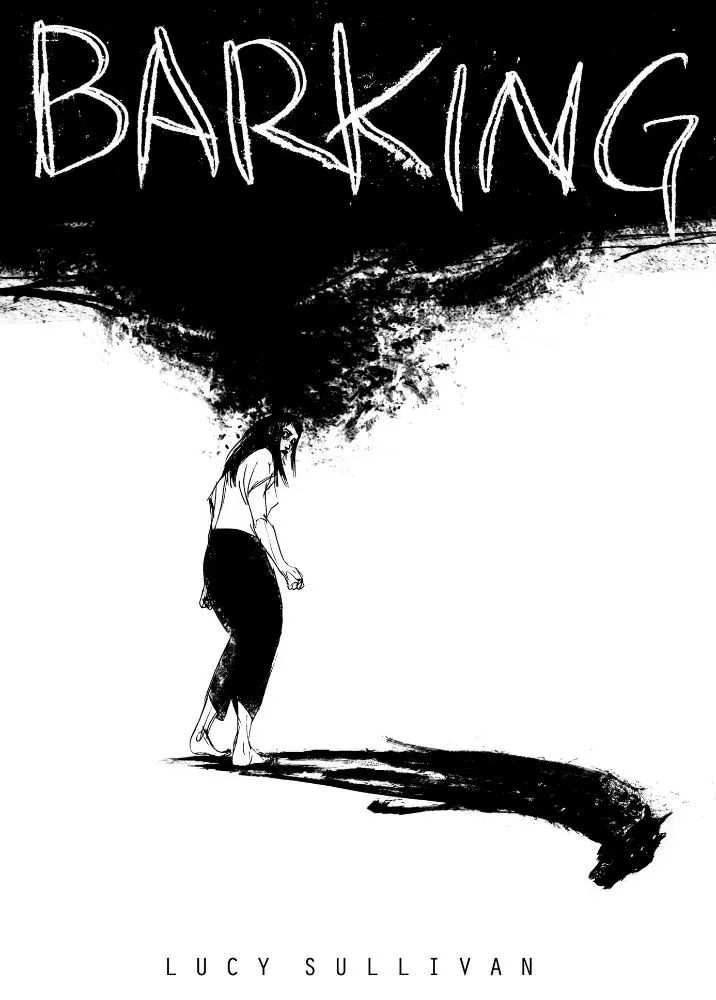

In Barking, you use handwritten text that sprawls out from the text into the panels, blurring the line between narrative and reality. What was your process forming the visual features of the novel?

First, I plotted the full story before drawing, akin to a film script. Then, I broke the story into chapters; this allowed space for a set-up, points I wanted to make about mental health crisis care, and a crucial change in the closing chapter. I had previously spent a significant amount of time developing the visual style of Barking while I researched the themes with a development sketchbook. The difficulty with creating graphic narratives is allowing time to draw everything you write. It’s a long, laborious process, so it’s wise to make sure you can complete it.

To depict the experience of a mental health crisis, the art had to have a sense of urgency. So, the reader could feel the grip of psychosis, layouts flowed with the protagonist’s state of mind, and the lettering overwhelmed and contrasted reality.

It took time to find the layouts and narrative devices. I realized the art needed to not be overly planned, so I wrote loose dialogue and action in scenes, sketching freely until a chapter started to form. It was a very experimental approach to making a graphic novel, and perhaps one I wouldn’t repeat, but it was the only way to make Barking. Telling stories from such a personal place felt, at times, like an exorcism. I banished the demons of my past onto the page in carbon and hopefully I’ve trapped them there. It was a difficult book to create, but it’s reception by readers has been incredibly cathartic.

Your story features significant themes of grief and depression. If you could change anything about the way these issues are represented in media, what would you like most to see? And how did you channel these thoughts during the writing of Barking?

I had specific hangups about the depiction of both. Part of what caused me to end up in such a bad place, was how narrow our understanding is. Grief is always linked to loss; it’s seen as devastating at first, but something that society expects you to get over very quickly.

It can also manifest in various guises. I was sad, but I was also furious at the world. My loss made me aggressive and unsympathetic to the point that people couldn’t see that what I was struggling with was destroying me. Feminine rage is an uncomfortable image, so I was keen to bring that to the forefront in Barking.

If you picture someone as depressed it will be a slumped over figure, locking themselves away. I was the opposite. I had three jobs, a busy social life, and on the surface, seemed to be coping, but I was also drinking heavily and getting into dangerous situations.

Apparently, anger is viewed as a more masculine response, so I wanted Barking to challenge how we think people behave when they crumble; how their ethnicity and gender affects that, as does the sympathetic nature of their behavior. Difficult people are not easy to help, but they probably need it more.

Alix’s inner world takes center stage throughout the text, and at times it is difficult to know what is real or unreal within her world. How did you strike a balance between depicting the all-consuming manifestations of Alix’s mind with the wider story?

It was important for me that readers felt as disorientated as Alix does in her crisis. However, I wanted to make sure I didn’t lose them entirely. I chose to keep realistic time frames by adding time stamps and dates to each chapter. The story is set 18 months after the death of Alix’s friend to address that aspect of grieving. I used research, and anecdotes from friends, to get accurate timings for the sectioning process at NHS hospitals.

I know some readers have struggled to keep pace with the book. It’s a challenging read both in content and visuals. I thought I might only get one chance to make a book like this, so I decided not to compromise my vision. I’m glad, as many have embraced its chaotic nature and found it an emotional read.

Though the story features elements of realism and psychological drama it also incorporates aspects of horror. Were you inspired by any horror projects or concepts in crafting the hound voice that stalks Alix?

When you start developing stories, you realize how much of your world view is based in folklore and film tropes, at least it is in my case. I knew early on that I would depict the depression as the “Black Dog” symbol.

I was discussing the links to Black Dogs and doom with my partner when he mentioned Old Shuck. It’s Yorkshire lore about a beast that roams the moors. It originates down south in Suffolk and is known as Black Shuck. It’s the inspiration for The Hounds of The Baskervilles and reminded me of other tales with black dogs that signaled death.

I was profoundly affected by An American Werewolf in London as a child. I saw it way too young, after the death of my best friend when I was 6 years old. The sections where the protagonist talks to his dead friend were incredibly soothing to my mind. I realize now that I created my own lore around death based on that experience. It’s hugely influential in Barking.

You’ve stated that Barking was inspired by your own mental-health experiences; do you have any advice on how to approach incorporating real-world experiences into artistic expression?

This is such an individual path to tread. Originally, I was going to create a story with myself as the protagonist, but I found I depicted myself in a much more positive light than in reality. It was incredibly difficult to draw myself, acting as I did, going though the worst memories I had, and be brutally honest. So, I started sketching character ideas and found it much easier to be open about my experience through Alix Otto.

Sometimes, I think you can get a message through better with fiction than reality. Add a dash of horror, ghostly tropes, or a phantasmagorical beast, and readers might be more inclined to take it on board. It also allowed me to incorporate not just my experiences, but the experiences of friends and the wider mental health system.

It’s not only yourself in these stories. If you decide to take the more realistic approach, make sure you speak to anyone living that may be included and consider the social and emotional repercussions. My own family have found it very difficult to read Barking. Many people didn’t realize what I was going through, and I found it impossible to tell them. But through Alix, they can now see, and it’s there if they want to know more.

Barking was your debut piece, but you have new projects upcoming that also center around difficult issues in modern culture. What is your next work about?

My next project, Shelter, is a folk-horror series set in late 60s/early 70s West London. It’s inspired by my dad’s childhood amongst the Irish community, my own childhood growing up in a live-music pub, and our eclectic regulars alongside my love of Celtic folklore. I wanted to create a story that focuses on the women of a community and how immigrant groups form networks to protect themselves in hostile environments.

Lastly, do you have any advice you’d like to share for aspiring writers hoping to break into the publishing industry?

I certainly do! Firstly, whatever idea you have just get making it. Make the book you want to make, not what you think readers want—they will find you. Chat to other authors, chat to publishers and bookstores but don’t just pitch your idea at people, be interested in what they do. Be active in your part of the industry: join local groups, support other creators, form a work-in-progress group to support each other. Creating books can be really isolating so find your people and grow your community.

If, and when, publishers or agents show interest don’t just sign that contract! Join a union such as Society of Authors who will vet contracts. You can always negotiate with decent publishers, so hold onto copyright, creative control, adaption rights and moral rights as much as possible. Talk to other authors represented by them who are willing to share their experience.

Finally, don’t lose heart if success doesn’t happen quickly. Publishing is a long game, so stick with it and your time will come. It’s a competitive industry and those at the top are a minority so do it for the love of doing it and just enjoy it. Everything else is a bonus on being able to do something as cool as making stories. Best of luck!