3:01

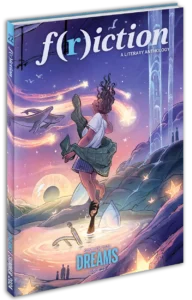

Words By Jennifer Wortman, Art By Lia Liao

My husband didn’t return to me as an animal or ghost. He didn’t send messages in code or possess other people to reach me. My dreams of him were just dreams, subconscious flotsam and jetsam. I’d stopped searching for signs of him. But a part of me was still waiting for him, and waiting was just searching in reverse.

Sometimes, late at night, I snuck off to my neighbor’s place to consort with the living.

There was another man, a divorce lawyer, I sometimes saw too. The twenty-year-old I was trying to be loved to indulge her warped sense of time: What day is it? What year? My disorientation was real, but I embraced it. But the part of me that knew exactly what she was doing also knew, exactly to the day, when six months since my husband’s death had passed. And on that day, that part of me said it was time to grow the fuck up.

That night, my eyelids popped open like some horror-movie doll’s and the time blazed blue across the room: 3:01. The clock practically spoke, its phantom voice insinuating, insistent: neither my own nor my husband’s. But maybe death had changed him. What was he trying to say?

These were precisely the kinds of thoughts I could no longer abide. I flipped on the light, grabbed the nearest book, and pretended to read until I pretended to sleep.

The next night it happened again: the sudden opening of eyes greeted by a bright 3:01. I sat up and almost reached out to clutch the handle of the three. Then I remembered: Just numbers.

But why those numbers? My husband had died in the afternoon: one-something, no threes. And why not an even hour? Why that pointer finger of an extra minute? To what did it point?

Perhaps at me, at my compulsive need to look for answers where there were none. Or maybe it was just scolding me for not looking hard enough. Maybe the very grief that had driven me to seek my husband had clouded my seeing, as it had clouded everything else, and he inhabited myriad mysterious forms I couldn’t discern.

So be it. I was determined to now grieve like a good Anglo-American, or better yet, a made-for-TV upper-class Brit. Like the very best citizen, I would work and work to refill our emptying coffers and cram my mind with useful thoughts. Most importantly, I would focus my efforts on parenting: I would not flee to my room to protect my daughters from my madness and misery or, worse yet, to protect myself from theirs.

Still, every night I awoke at 3:01. With every new wake-up, the numbers grew—larger, closer, breaking free from the clock. Soon, they broke free from the dark. One afternoon, the electricity fritzed out. When I checked my phone to reset the clock, it was 3:01. I ran to the store to get groceries: the timestamp on my receipt said 3:01. A self-help book I was proofreading used, as a negative example, someone who stayed up each night until 3:01. “Typo?” I wrote in the margins. Maybe it was a typo, but it wasn’t, I knew, a mistake.

When my oldest called home from school with a migraine, I barely glanced at the time. I already knew what it would say: I was right. In the car on our way home, I couldn’t help quizzing her about the circumstances of her headache: Had it come on gradually or suddenly? How much time had passed between its onset and her phone call? Did she feel a sense of urgency when she called me or was she listless?

“I don’t know,” she said. “Why are you asking me all these weird questions?”

I couldn’t tell her that I hoped her father was somehow communicating with me through her.

I wanted to believe, but didn’t believe it enough to risk her believing it, too. When we got home, I fed her ibuprofen and fled to my room.

My husband and I used to read to the girls before bed, but by each day’s end, I could barely function. My oldest now played phone games long into the night and my youngest raced around the house in circles. I understood that the distress I forced myself to feel about this came from a rarified set of values based on culture and class, one in which my children were supposedly in training to become both masters of the universe and responsible citizens who were to “better” the world while collecting on their advantages. On the other hand, I knew the importance of self-discipline and sleep for basic well-being from my own chronic lack of both. I also knew I was allowing their behavior not out of a revolutionary spirit but because it was easier to ignore it.

One night, after my youngest had supposedly gone to sleep, her feet once more quaked the house. I loved her thumps, the micro and macro rhythms, the jackhammer and the pause. Still, I wrenched myself out of my bed.

“Hey there,” I chirped. My youngest glanced at me and kept moving, her beige hair flapping wildly. I tried again. “It’s late. You should be in bed.”

“I can’t,” she said, still running. “Liv kicked me out.”

“Kicked you out?” I barged into their shared bedroom. “Did you kick out your sister? From her own room?”

“If I had my own room,” she said, “I wouldn’t have to.”

“We’ve been over this,” I said, my jaw clamping to staunch my fury. “I’m still trying to figure out how we can keep this house, so you can forget getting a bigger one. You know there are whole giant families that share one room apartments, right? Count your blessings.” When she blinked her disdain at my platitudes, I yelled: “This is what you care about now, of all things? This?”

She turtled her head. “I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, but it came out snappish. I tried again. “I’m sorry.” In the rest of our little house, my youngest continued to thump around. “I’m going to get Ava now.”

“But Ava won’t stop talking,” she said, clutching her hands as if around a little neck.

“Ava’s just sad. We all are. It’s okay.”

“But that doesn’t make sense. How can everyone being sad be okay? That’s, like, the opposite of okay.”

“I don’t know,” I said, my answer to everything.

Before she could respond, I slipped out of the room and tried to stop my youngest. But she made a game of it. She hopped on the couch, pouncing on the arm that had already caved in from her previous pouncing, then climbed the top of the couch that had already split open from her climbing. The more she hopped around, the younger she seemed, as if she were traveling back to the lost time, when she was five or three instead of nine, before her father got sick and died. She found her own antics hilarious and started narrating her moves, using her chosen regression persona, “the doggo.”

“The doggo is running away from the mommo!” she cried. “The doggo is jumping on the doggo couch.”

“It’s late, sweetie,” I said. “That’s enough.”

“The doggo needs exercise.”

“The doggo needs sleep.”

“The doggo needs to chase a squirrel.”

I tried to intercept her and missed. She shrieked with delight. Then I grabbed at her again and she tripped and went crashing, headfirst, into the wall, the frenzied glee knocked so completely out of her that I longed for its instant return.

She palmed the top of her head. I was already seeing stretchers, hospital beds, the hidden hematoma that fatally burst. At the same time, I refused to believe anything could be wrong.

“I’m okay,” she said, before I could ask. “I just need a little ice.” She went to the freezer and pulled out the cold pack my husband had long ago purchased for such occasions. Even now, I expected him to rush ahead and grab it for her himself.

Now my oldest was up, asking questions and holding the ice pack to my youngest’s head. I so loved them both and I wanted to sleep forever. How could such impulses coexist? When I finally got my girls to bed, I set my alarm, to check on my youngest, for 2:58 a.m.: enough time to fully wake up before 3:01 and not enough to fall asleep again then arise at the fateful time. I would break the pattern, whatever it augured. When the inevitable display of numbers appeared, I would stare them down and bid them farewell.

But I awoke as I usually did, disturbed by nothing but my own brain, at 3:01.

I smiled. I suppose I was thrilled. Not so long ago, I would have spoken to my dead husband about 3:01 and imagined his response. But in that moment, I found that I couldn’t do it anymore. His silence had grown too loud for me to talk over.

In the soft black of my daughters’ room, I sat on the edge of my youngest’s bed and inhaled her warm sugary scent. I wanted to tuck myself behind her, glue myself to her folds, the way I used to, sometimes, with my husband when I couldn’t sleep. Above, my oldest nested beneath her comforter, her thumb, I knew, poised nostalgically against her mouth.

I began the careful climb over my youngest. Her eyes flew open, the whites piercing the night. “Mom?” she said, gazing up at me. It seemed like a big question, all the hope and need and trust packed inside that small, dull word.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s just me.”