A Review of Love Letters from an Arsonist by David van den Berg

Words By Dominic Loise

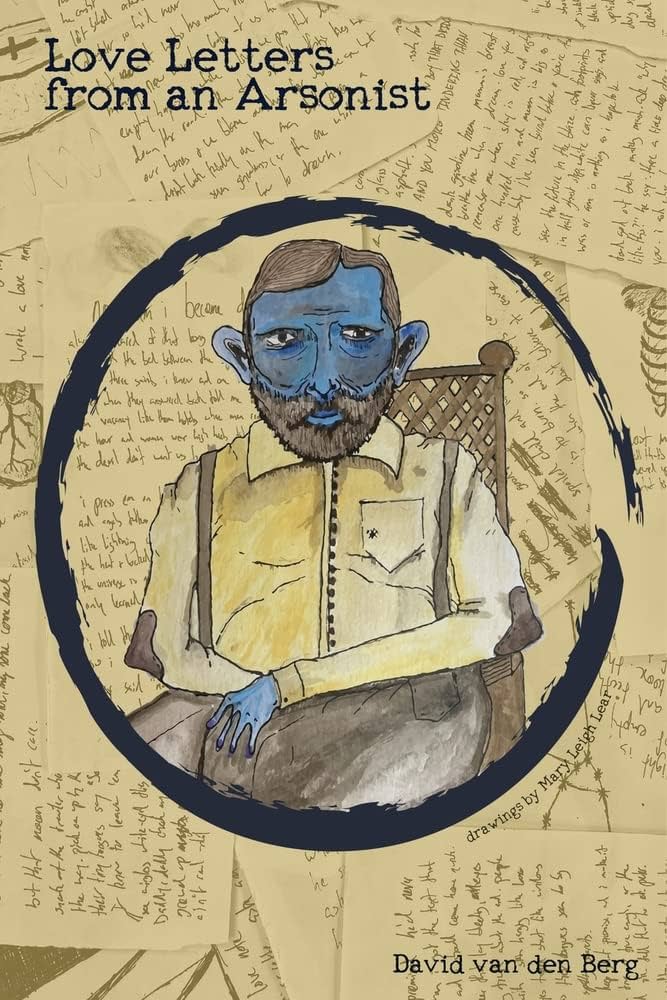

Setting and self are at the center of David van den Berg’s poetry collection Love Letters from an Arsonist. Van den Berg’s poems are rooted in a southern gothic tone borrowed from generations of people who have been contained by their environment, just like the fantasy creatures he describes lurking in the dark shadows. The metaphysical and mystical are both misfigured by the surroundings of the Florida outskirts as van den Berg tries to process the environments around him: natural, unnatural, and familial.

The collection is divided into three parts. The first two sections examine the anger in feeling powerless and the immobility found in the South. The third section travels past the self-righteousness of places rooted in traditional values when resisting the benefits of modernization, and moves on to confront the act of self-loathing. Each section excavates and explores loneliness until the only option is to rise above our environment and change the story, rather than continue the same narrative of previous generations.

Salt River Blues is the first section of poems and takes a closer look at the underbelly of what haunts us when reflecting on our monstrous selves. Among immobile people wishing for less enlightened times, it gives a sense that America has moved past the ancient deities—but some immortal legends such as European mythical creatures, voodoo spells, and Lovecraft tales still wander these backroads. There are allusions to this in the title poem of this section, “mudcats sing ‘bout mermaids what grow whiskers and choose tobacco over princes.” Van den Berg’s poems also give the sense of growing up around people pushed to the fringes of commercial society. The men are portrayed as sons of Argonauts, landlocked in trailers, narrating dated folklore around campfires. The women, on the other hand, appear as daughters of Circe who know the unspoken ways of dealing with problems.

Mythical creatures are pickled and morphed while God drinks moonshine from empty mason jars as we transition into the second section, The Midnight Gospel, which has a more biblical approach with the poet as seeker. Here he is confronting the mystical head on—instead of it being an unknown entity—to explain the surroundings outside mainstream society. As the poet is a seeker on the way to understanding the self, he is no longer looking into the deep pools and caves of myth. Instead, he finds God and ends up disappointed that the almighty is like him, searching for reprieve in shallow liquor glasses. This leads to the realization that we need to face our own flaws. If God is man, then God is fallible. In the poems in this section, God is questioned in bars or whichever dirty dive the deity is found in and the answers received come short and direct like shot glass wisdom. In “Prayer For Peace,”the deity’s response to the question of peace is, “he asked if we had tried killin’ other peoples’ kid”, and“he said maybe if we kept it up we’d figure things out”, while walking off with his drink.

The third section, Pinecone Son, is about learning to lean on ourselves to make the changes we are looking for in life. The title of this section comes from the poem the book is named after. It borrows from Love Letters from an Arsonist’s opening line, “daddy was a wildfire burned hisself inside out / spat out pinecone sons what can only grow in flames’,which define how this section deals with the poet working to replant himself in a nontoxic environment and rise above the smoke screen of others to see the world clearly with his own vision. The poems hereare about breaking the cycle of parental expectations, overcoming the limitations of where we grew up, learning to set expectations for ourselves, and being open to help from strangers. The poem “Fly United” appreciates a man from the Ivory Coast experiencing and expressing joy on an airplane with his plea, “and if you have that light in you, i ask you now share it just a little more often for those like me who live in darkness and spend our lives without”. “Mithras Rising” is about an unseen stranger helping someone after a night of drinking as “he stumbled out the door at 2 am,” and wakes up on the beach afterwards, discovering“next to the pants he found a full bottle of water and an unopened pack of crackers and on the bottle were three words, written in sharpie: ‘love yourself more’.”It gives the reader a sense that the poet has found a way out of the trap of generational patterns and that he can close the door on the past to start finding peace in the present.

Love Letters from an Arsonist is a poetry collection that can be read multiple times. David van den Berg has put much thought into how these pieces connect, and how they flow together not only as we read them in succession, but even when they are divided across three sections. Each part also portrays stories about where we come from, where we are going, or the consequences of staying immobile at the crossroads of indecision yet circumventing ‘The Fates’ of becoming immortal through passed-down stories. This last part the poet accomplishes by writing about breaking the cycle of family stories to tell our own, and how to cut off from the bad branch of the ancestral tree and not become another infamous character in local lore.

I would recommend this collection for anyone haunted by their past and in search of their current self. In its whole, Love Letters from an Arsonist is a poetry collection that puts on paper a roadmap of growth for both a poet and a person.

Love Letters from an Arsonist is available now from April Gloaming.