The Letter of Doom

Words By Esther Bewaji, Art By Hailey Renee Brown

Another student received the notice yesterday. Thin white paper, bluish and dried ink etched on the page like a tattoo drawn in sloppy cursive. Its head stuck out of the mailbox; a threat so huge it begged for attention. The reactions were all the same—confusion, shock, and then shame. How could a stranger know their deepest, darkest secret?

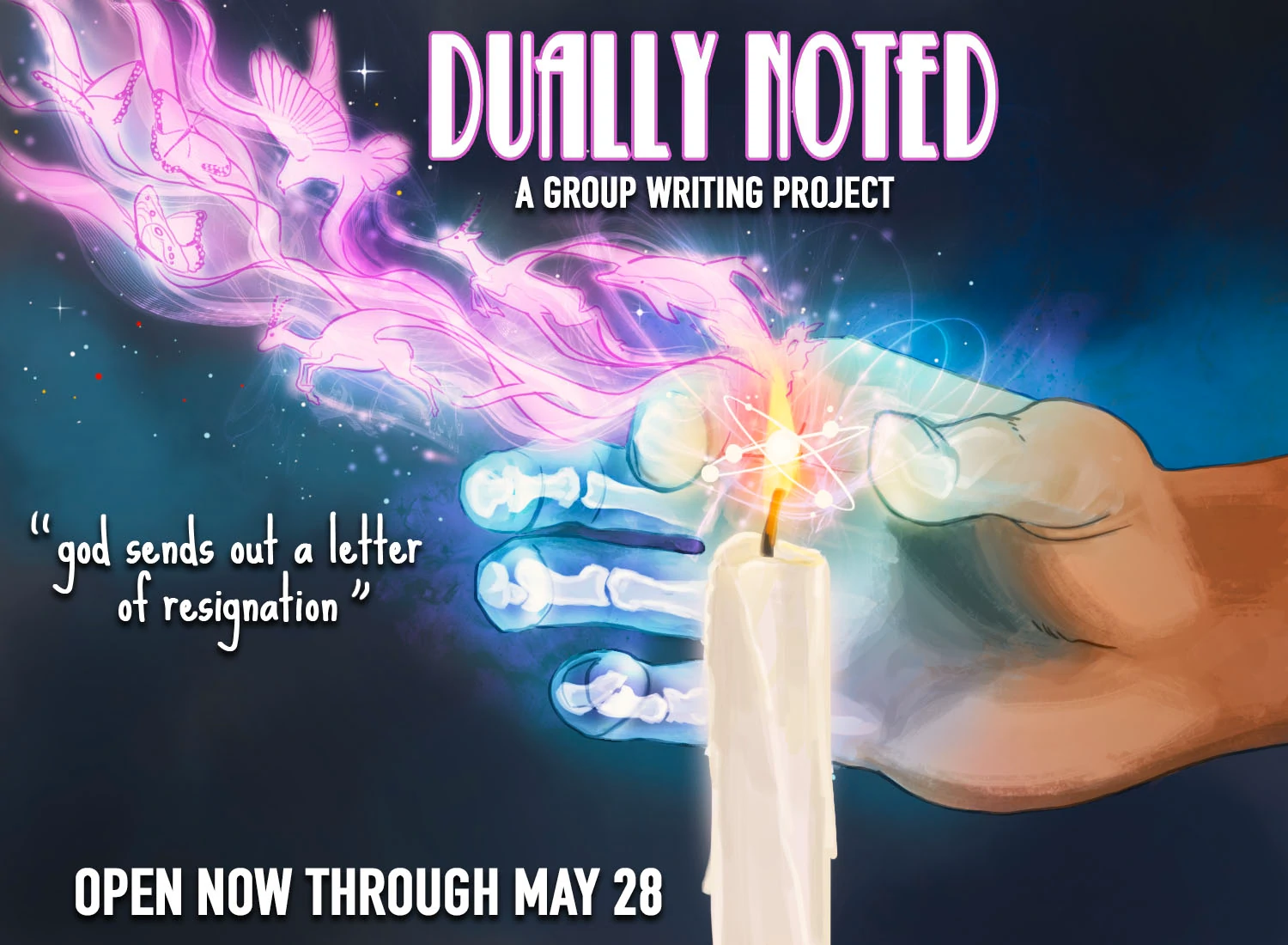

People called it The Letter of Doom. It went from being the town joke to a phantom whose name you must whisper to say. The unknown perpetrator had become a god, respected and feared among the students.

The first person who got the letter was a girl in my school called Amanda. She’d been sneaking out of her house almost every weekend to see her college boyfriend until the angels caught her red-handed. Parents liked these anonymous letters because they had become easy microscopes that looked into the lives of their teens. Some found it creepy but were still curious enough to check the mailbox that no one used for any report. Funnily enough, the letters were hardly ever wrong.

Samuel had gotten one exposing his cigarette use, much to his parent’s dismay. The infamous drug dealer, Ife, had also gotten one, not to anyone’s surprise. The neighborhood teens called her igbolabi, a Yoruba word meaning “we gave birth to weed.”

I’ve been waiting for my letter to come in, since I have become quite fond of slipping fingers in between my thighs like a hook in the sea, always coming out with a piece of me much bigger than before. Bending and twisting like a contortionist.

But I guess it’s harder to spot a sin committed in the hidden crevices of hell, that is, my room where no inquisitive spirit can slip through. When I’m not doing myself, I’m watching other people on tiny, dim screens either in the church parking lot or during lunch in the locker room.

My friend Jasmine and I were talking about the letter a few days ago. I laughed as I narrated the hilarious response of my neighbors when their son got the death sentence. She said it was more of an indifference sentence. The tone was less warning and more declarative like God was simply telling you the fact of your sins rather than warning you to repent. They had become resigned to them, to you.

Monday morning, my mum glanced at the mailbox from the kitchen. She was one of those mums. She didn’t say anything about the letter but she was waiting and so was I so I could snatch it before her eyes caught sight of it. I got ready and went outside with my bag strapped on my back, rushing towards the bus. I stopped. There it was—a folded sheet of paper peeking out of my mailbox. I pulled it out and sure enough, the illegible cursive handwriting stared back at me on the page. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.