What Stephen King’s Memoir, On Writing, Taught Me About Embracing the Unknown

Words By Jessenia Hernandez

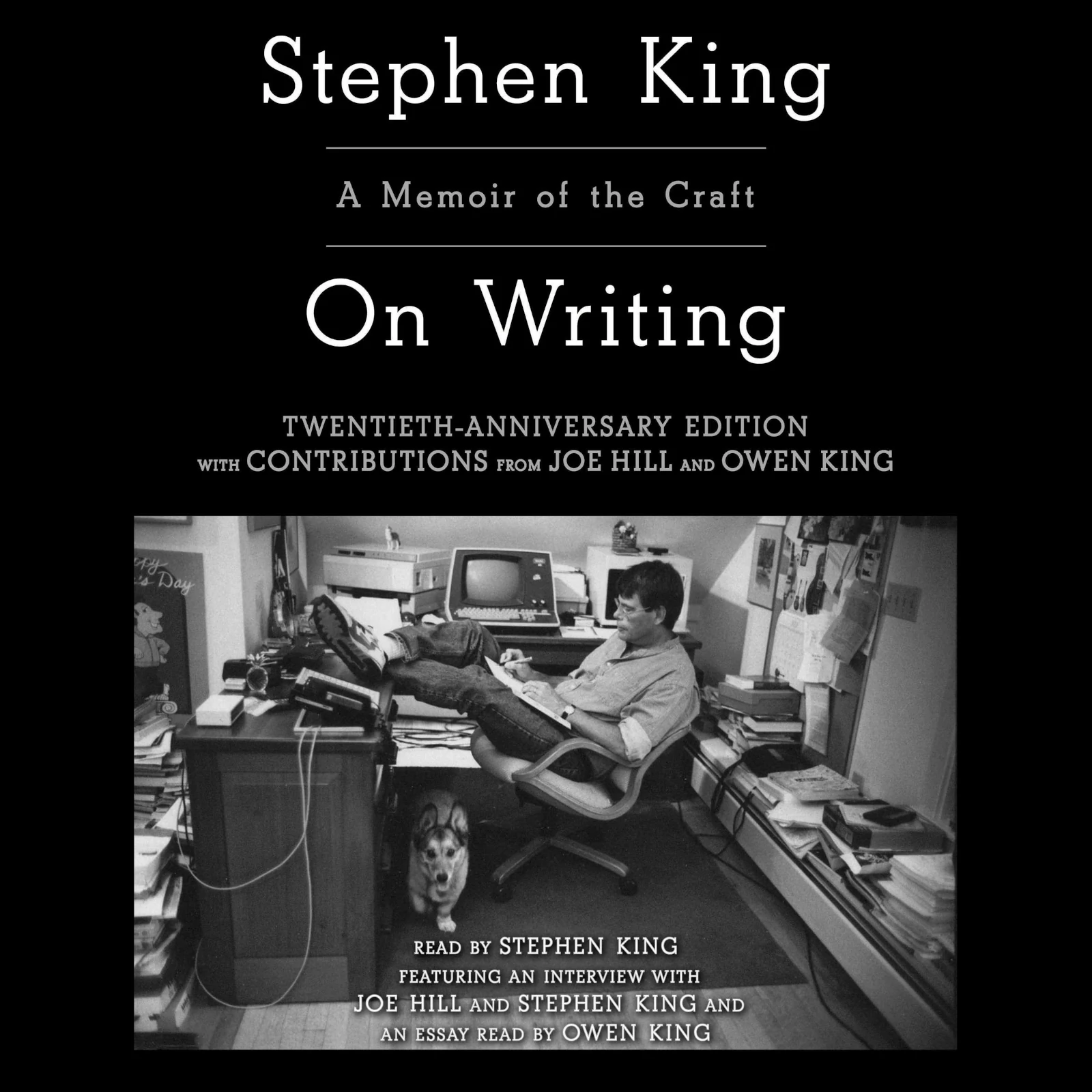

Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is part recollection of the critically acclaimed author’s life and part guide to succeeding as a writer. In high school, King began working for the Lisbon Weekly Enterprise, where he received a piece of advice from the editor that he returns to throughout his book: “write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open” (57). In On Writing, readers peer behind the closed door, the private and mystical place where Stephen King has woven together more than sixty novels (and that’s only counting the ones that have been published).

How could one person achieve such a gargantuan literary portfolio with so many well-loved books? What is his secret? A common idea that connects much of King’s advice, and the overarching answer to questions like these, is to embrace the unknown in writing. King’s approach to writing suggests that a story should be carefully drawn out. It is not necessarily controlled by the writer but discovered and then honed. Here is King’s advice on writing to assuage some of the worries uncertain writers commonly experience.

1. What if I can’t make money with my writing?

Many writers worry they will not be successful. They ask themselves questions such as, “Will people like it?” “Will I be able to support myself with my writing?” and “Is it worthwhile spending time doing something I love over something that pays?” The following advice from King may help quell these anxieties:

What would be very wrong, I think, is to turn away from what you know and like . . . in favor of things you believe will impress your friends, relatives, and writing-circle colleagues. What’s equally wrong is the deliberate turning toward some genre or type of fiction in order to make money. (159)

In other words, never compromise on what you want to write because you’re not sure how others will receive it. Don’t alter your story to please an audience because pleasing everyone is impossible. Instead, embrace not knowing how many people or who will connect with your story and simply make sure you connect with your story. You may not know what that story is yet, but King believes you’ll find it. He encourages writers to “Let your hope of success (and your fear of failure) carry you on, difficult as that can be” (210). All you have is you and your words—from that will come the story you want to tell.

2. What if it isn’t important or deep enough?

As a writer, I’ve worried if my writing will be meaningful and impactful. Will my readers reach the end of my book and be able to draw connections they didn’t see in the beginning? Is my subject important enough? Here’s the thing: you can’t possibly know exactly what your story will look like in the final draft the first time you sit down to write it—or even the second, third or tenth time.

King believes that “. . . starting with the questions and thematic concerns is a recipe for bad fiction. Good fiction always begins with story and progresses to theme; it almost never begins with theme and progresses to story” (208). Don’t waste time worrying whether Bobby’s green jacket represents life or greed or envy. Instead focus on writing down that Bobby is wearing a green jacket. You may discover this means something later. This is the purpose of rewriting, a practice King strongly advocates for, in your second and third drafts. Don’t fear a connection you might fail to make in your story before you’ve even given yourself the chance to make it.

3. What if I haven’t come up with the ending?

Many writers feel an immense pressure to know their story inside and out from the beginning. I’ve always been envious of authors who claim to have had their story’s characters and world in their head for years. But King helped me realize that it’s okay if you don’t know your entire story when you sit down to write it. Don’t let the unknown paralyze you. Instead, embrace and celebrate it—there’s so much possibility ahead of you! King suggests that outlines and character notes aren’t essential, or even helpful. He says:

Stories aren’t souvenir tee-shirts or GameBoys. Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered pre-existing world. The writer’s job is to use the tolls in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground intact as possible. (163-164)

It’s exciting to feel that your story always already existed and your job is simply to excavate and narrate it. When King began writing his eventual bestseller Misery, he says that the story only existed as “a relic buried . . . in the earth . . .” He goes on to explain, “but knowing the story wasn’t necessary for me to begin work. I had located the fossil; the rest, I knew, would consist of careful excavation” (167). The excitement of an archeologist’s work is in the unknown: the possibility of what can be uncovered. As writers we can approach our craft the same way.

4. What if I don’t even know where to start?

King outlines the progression of writing as such:

The situation comes first. The characters—always flat and unfeatured, to begin with—come next. Once these things are fixed in my mind, I begin to narrate. I often have an idea of what the outcome may be, but I have never demanded of a set of characters that they do things my way. On the contrary, I want them to do things their way. In some instances, the outcome is what I visualized. In most, however, it’s something I never expected. (165)

There are two important things to note here. One, all you need to start writing is a situation. Don’t overthink it, don’t make it too complex, just have a simple premise. For example, in Misery, it was a psychotic fan holding her favorite author hostage. Two, you can’t control what your characters do. If your characters are honest and interesting, you’ll find them doing things, as King says, that you never expected. You may not know now where your characters will end up, but they will begin to grow and make the decisions as you go.

5. What if this isn’t enough for my reader to really get it?

King encourages writers to embrace what their readers don’t know—or rather what the writer withholds from them. Writers tend to overshare to make sure the reader gets it, but usually the readers’ imagination will do the work for you. One example of this is description, which King believes “begins in the writer’s imagination, but should finish in the reader’s” (174). Though you may worry about not being detailed or specific enough, when it comes to description, you risk taking the reader out of the text by giving too much. What if your idea of the most horrifying monster to exist is a far cry from the reader’s? Let them imagine their version with the few details you do give them, such as the sounds your monster makes or its foul odor.

King also believes in describing setting delicately. While certain details can tantalize the senses and immerse the reader, too much can quickly bring them out of your story. King says that as a writer, “your job is to say what you see, and then to get on with your story” (180). Beyond some details to ground the reader, the physical description of the setting is not important. Instead, include details that further the story, such as the setting’s significance or usefulness to the protagonist. The same applies to backstory and research, where King believes details should be kept to only the most relevant and interesting. In keeping things unknown to your reader, you’ll create a much more engaging and intentional story.

Final Advice from On Writing

Ultimately, in On Writing, King urges writers not to take the phrase “write what you know” too literally. In writing fiction, one must be willing to venture into the unknown. King’s horror novels, filled with killing, gore and monsters, are a testament to this. While it is beneficial to write from experience and prior knowledge, King suggests that it’s also worthwhile to pay attention to what your heart and imagination can conjure. He says, “If not for heart and imagination, the world of fiction would be a pretty seedy place. It might not even exist at all” (158). So, if you’re going to embrace any aspect of the unknown throughout your writing journey, embrace what could be when you let your heart and imagination guide you. Trust your instincts instead of fearing that there may be better words to use or stories to tell. As you march forward into uncharted territories of writing, whatever they may look like for you, here’s one last piece of wisdom from On Writing:

At its most basic we are only discussing a learned skill, but do we not agree that sometimes the most basic skills can create things far beyond our expectations? We are talking about tools and carpentry, about words and style . . . but as we move along, you’d do well to remember that we are also talking about magic. (137)