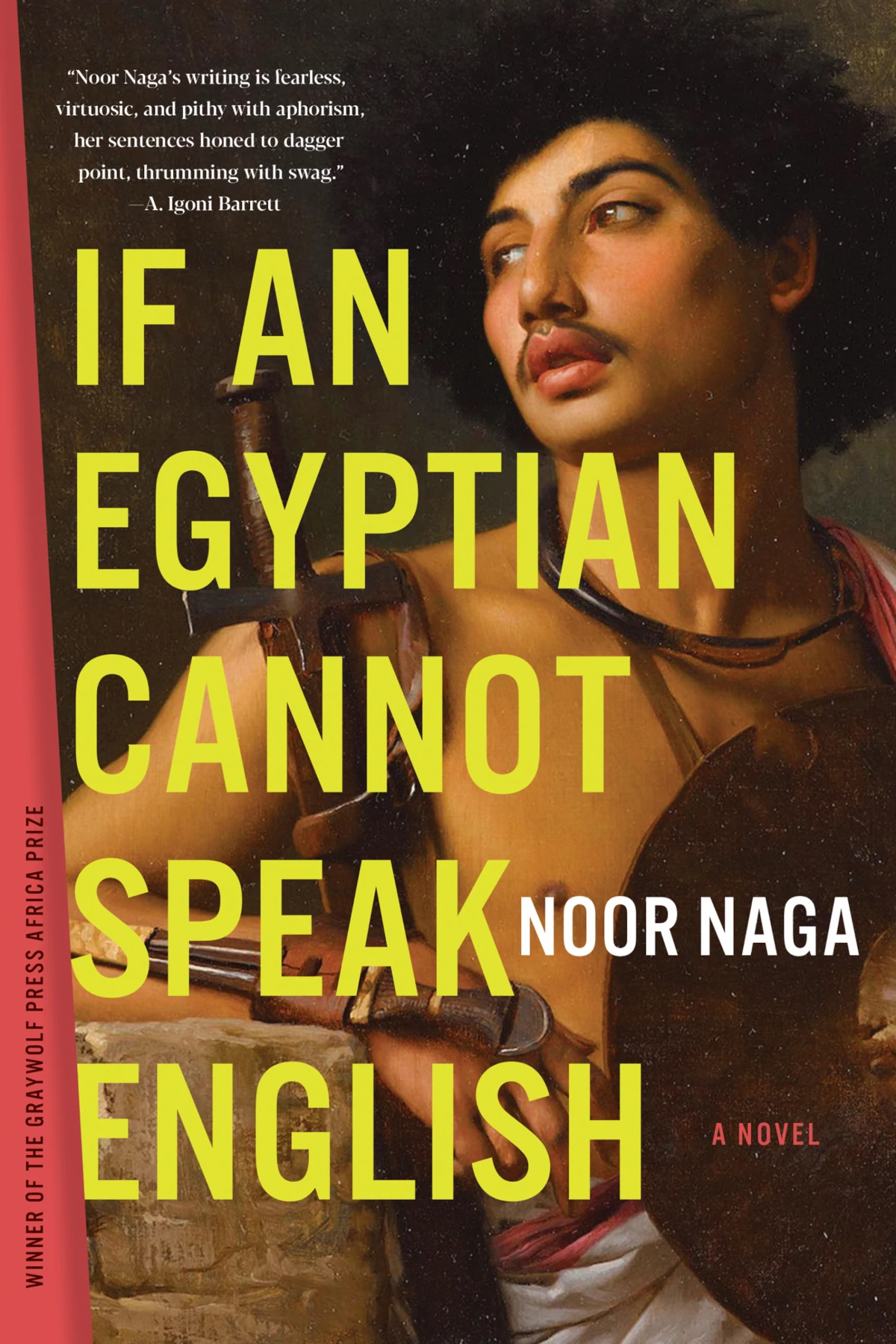

A Review of If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga

Words By Manal Ahmed

To be published April 5, 2022 by Graywolf Press

Noor Naga’s novel If An Egyptian Cannot Speak English is a masterclass in complex characters and incisive writing. It is a novel deeply aware of itself—just when you think you know what the writer is trying to do, she surprises you. It is as though the book is consistently conscious of its ambitions as well as its shortcomings, harboring some secret knowledge that the reader is not always privy to. Operating from this knowing distance, it presents difficult notions of identity, otherness, gender, and race, splaying all these themes out in their entirety and asking us to look and closely examine what is in front of us. And in participating in this active examination, the reader becomes an inextricable part of the novel itself. Because so much of the novel interrogates notions of power, it becomes important who gets to tell the story, and who gets to read it, too.

The novel is centered around the story of an Egyptian-American woman and a man from Shobrakheit who meet in Cairo and the pain, love, abuse, and power that is ever-present in their dynamic. Products of their histories, the two cannot extract themselves from what precedes them. And yet, Naga is not writing a story merely about identity, but instead how our ideas of identity might be limiting. Her characters are not one-dimensional, nor do they defy or uphold stereotypes as if to make some sort of statement. They just exist in all their multiplicities. And her writing is at its best when she lets the interactions between her characters speak for themselves, allowing us to fill in the gaps. In one scene, the boy from Shobrakheit—always unnamed—calls the girl “a whore in ten different ways” and then suddenly he is “crying on [her] living room floor” in child’s pose. Naga frequently juxtaposes moments of absolute vulnerability and abhorrent power like this, so that the reader—and the characters too—reckon with the ways human beings can inflict immeasurable pain on others while also being in pain themselves. In the same scene, Naga then inserts the girl’s thought: “Why is this pity I feel so frightening?” and the sharpness of this sentence cuts through the paragraph with such intensity I had to take a break upon reading it.

Consider also the weight and painful beauty of these two sentences: “She wouldn’t let me kiss her like I used to. When I tried, she bowed her head into my chest and that was all, my hair dripping on her like a tree after good rain, and the two of us fragile as birds.” The novel thrums with such precise yet poetic language. And for all their shifting power (his because he is a man and knows the city well, hers because she is American and rich), in the end, the two really are fragile beings caught in a complex web of inadequacy and powerlessness.

The novel works less when the writing becomes obvious and Naga is directing us into exactly what to think. For instance, at one point, the girl launches into a series of rhetorical questions. She asks “Why did he choose me in the first place? Was it because I was neither of him nor truly other?” This kind of writing can sometimes feel as if it is leading to a place already obvious to the reader. Such instances, however, are far and few in between. As a whole, the novel does justice to the intricacy it explores. It is wholly captivating and will challenge you in ways you don’t see coming.