An Interview with Tex Gresham

Words By Tex Gresham, Interviewed by Thomas Chisholm

This being your first novel, how did you know when you were done? How many shelved novels came before this one and do you think you’ll take any of them off the shelf?

There was a long time where I kept going, I’m done, but I was lying to myself. When I felt there was nothing more I could add, that’s when I was like alright, now I’m done.

I have four shelved works that came before this—three novels and a collection of stories. Two were straight-up horror, and I’ll probably rewrite them to make them more what I like now. Another I’m definitely going to bring back is an absurdist pulp-detective story called Hard Boiled Dick.

What is your writing process like? Do you sit down every day or have a ritual?

I’m of the mindset you don’t have to sit down every day. I think the demand to sit down every day is kind of cruel. You’re tapping into something special, and the idea of forcing it is cruel to that thing; you can’t force a plant to grow, you can only water it.

I give myself false deadlines, or I ask someone to give me a deadline. When inspiration hits I sit and write. I try to continuously work on something, be it a script or otherwise. I’m always alternating. I don’t really have a routine I just kind of work on stuff. When I get deeply involved in something I get obsessive and I work on it every day. But right now, I’m taking a break because Sunflower just came out and it’s a huge relief.

How did you find your voice?

I tried to write a certain way for a long time—introspective literary fiction—but then I got fed up with it and was like you know what, fart jokes, let’s go. I think you have to get really angry and disappointed, and then there’s going to be this breakdown of what you thought you wanted and what you thought you could do and how you wanted to do it. You’re going to be like forget it, I’m just going to do this, and you’re going to spitefully write something different, and you’ll realize I like that, that’s actually good. I can’t tell you how many bad stories I’ve written. Practice the bad, and the moment you’re fed up, that’s when you find your voice.

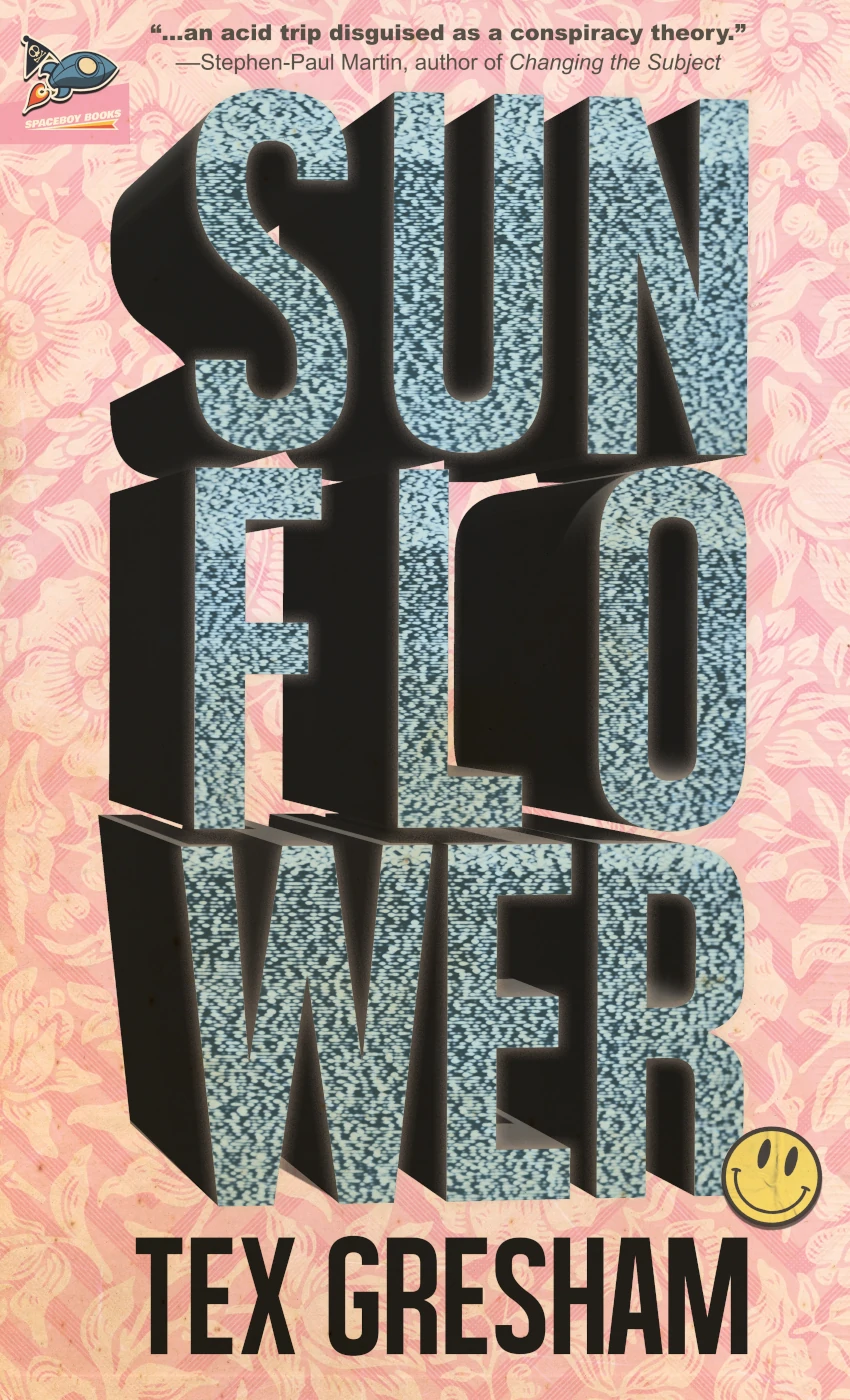

You spent about ten years working on Sunflower. Once it was finished, how long did it take to get published—from that moment of I know I’m done to signing with Spaceboy Books?

It was a weird process. I sent Spaceboy an older manuscript and told them there were some things I wanted to do with it, and they let me. It was probably a year of sending out the one I didn’t have anything more to add to, and then Spaceboy took it, and when they did I realized I wanted to rearrange things and make it bigger. Then, I realized that there’s more sci-fi elements in it than I anticipated. I saw they were interested in weird, innovative stuff and they let me play around with the manuscript. The freedom to make it however I wanted to make it really made me realize they were who I wanted to go with.

As for querying, it was a typical query but instead of the usual response you get from a query letter, we instead started a conversation. My experience querying agents was more formal but with Spaceboy, it became a casual conversation. A similar thing happened at Atlatl Press with Heck, Texas, where it was a casual conversation and I had the freedom to do what I wanted. When you and your publisher both love what you got going—that’s the key.

I’m curious how you devised the book’s structure. Did you always envision it in this nonlinear way?

It was always nonlinear. What changed when I sent it to Spaceboy was the inclusion of additional chapters, deleted scenes, and setting it up the way I did with the deleted scenes in the back. But start to finish, it was always exactly how it is. There wasn’t a whole lot of rearranging.

What came first, the story you wanted to tell, or the framework for telling it?

Both the framework and the characters. The first chapter—the one about Heather who is sick in her room and thinks she’s dying and she’s watching TV—that was the first thing I started writing for Sunflower. I wrote the Delta chapter next and then I started crafting those characters. The framework of Act One was to introduce these characters. Taking so long with the book’s intro, was the satirical framework that I wanted for the beginning. A movie should be quick in the first act but I wanted to take the most time I possibly could.

Your comedic timing is incredible; you often undercut dramatic scenes with a super funny joke, like a spoon full of sugar that helps the misery go down. Was it a goal to include comedy, or did it come naturally?

[laughs] I like that a lot. I wish I could put that on the cover now. My mindset is always: how can I make this really tragic moment be funny? The awkwardness of situations automatically makes me laugh. I kind of wanted a Looney Tunes vibe with the book. If you take away the funny moments of Looney Tunes, it is so unfunny; they are really demented and weird and violent. I think everything I write has to have something that’s funny, at least to me, and if other people see it as funny, great.

I’m drawn in by the macabre, visceral gore, and body horror in both of your books. What do you find compelling about those themes?

I get freaked out about the delicacy of the body—just a little bit of something can throw it all off. One little change can destroy. In Sunflower, it’s all about the idea that the individual is the body, not like this mind or spirit or whatever. Moments in the book like when the coyote turns inside out and things like that; they’re reiterations of that delicacy. Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation touches on that too, where the rearranging of the body can be horror. But it’s actually an evolutionary step and to see it as something fearful is to betray that evolution, and to embrace it is to embrace the future and transcend beyond the body.

One thing I really wanted for Sunflower while reading was a map of North America like you would see in a fantasy novel. Is that something you considered?

I think I wanted it to be vague and disorienting where you can’t get a grasp, but really it’s just the exact same thing as it is now. Except that above Santa Barbara, along the border of where Nevada and California meet and all the way down to Mexico, is broken off. Everything is the same . . . kind of. Because of that breaking off some things were rearranged—the concept of what hasn’t broken off and what hasn’t changed, the name, the laws, the rules and all that.

Sunflower seemed more influenced by film than literature; reading it felt more like the novelization of a film. The narrative mimics film storytelling devices—the camerawork, editing, and score are just as important as the plot. Was this a conscious choice because the story is about a script and the film industry, or is this your style as a novelist that you will continue using?

The next thing I’m working on is kind of but not really film-related, so I don’t know if I’ll continue to use it. Here, it was a conscious choice. Originally, the title was Sunflower: A Novelization of the Final Film by Simeon Wolpe and I wanted it to look like one of those movie tie-in novelizations. Some of those are really good. I read the novelization of John Carpenter’s The Thing, and story-wise, that book is superior to the movie. There’s all this stuff not in the movie because the script got cut for budget reasons and to make the film feel more claustrophobic. The book is a bit more expansive with the characters’ intricacies. So, the score, editing style, and cinematic techniques are in my novel because I wanted it to feel like reading a movie.

That’s very much how it feels. I also thought it felt more like a DVD with all the bonus features.

One of my original concepts for Sunflower was a release where I could somehow get it as two books in one box. There’d be the novel and a little extra bonus booklet, like the ones you get for a Criterion release. That’s what I wanted originally, a fake Criterion Collection release. I even had a mockup cover that I photoshopped.

To me, the book is begging to be adapted. Do you feel like that would be possible? Would a theatrical cut work with all the bonus material? What is your fantasy of that whole process?

I think it could make a decent miniseries, like a five-episode miniseries or something like that. I think it could be a movie. I’m working on a screenplay version that cuts out quite a bit, but because it’s more of the film version you have to lose certain things. It’s almost like Inherent Vice, where the movie cuts out a lot from the book. Some of it’s really important and interesting but when you watch the movie, it leaves out so much that you want to read the book. The movie intentionally leaves those blanks so that when you read the book it becomes a tandem, complimentary experience.

Do you prefer writing scripts or fiction? How do they inform each other for you as a writer?

I think going into a fiction-y thing, the plot is the first thing I think of. Then when I think of that I can throw it away and write what I want to write. There are restrictions with screenwriting and I like those because it’s like painting by numbers but in a good way; that structure makes it fun. I was a screenwriter first. I started writing scripts and then I came to fiction later. But I think screenwriting is harder. Fiction isn’t as hard because I could just write, write, write. With screenwriting, you have to make convincing moments for the story to move forward. Whereas with fiction, you can expand on things and clarify and present the emotion.

You’ve been getting recognition lately for writing scripts. How is that whole process going?

It’s going well. I’ve had some meetings with people and I’m working on something now that could be cool, we’ll see. I got hired to write something, so we’ll see what happens. No one’s really interested in buying or making my features yet, but I’m not going to stop writing. I feel like I’m on the right track. I just need to have the right conversation with the right person.

What are you working on now?

KKUURRTT and I started a press called 100 & 900% Press. We only publish collaborative work, and the first book we’re putting out is a collaborative-journal novel about two guys traveling across America on a vaguely disguised book tour. But in reality, they’re going to deliver drugs to someone. I also have a poetry book coming out from RlySrsLit called This Is Strange June, sort of like an autobiography in poetry. In 2023, Tolsun Books is putting out my short-story collection Violent Candy. As for scripts, I’m working on one called Toothhammer, which is about a retired boxer helping a young girl learn how to fight. The other one is my version of Uncut Gems but at a golf course.

My next big project that’s going to take time is what I’m calling Beyond the Map. It’s four novellas that connect and span time. It starts in the 1800s with a woman getting revenge on someone. Then it goes to the 1960s when a trans man faces the foreclosure of his library where people bring in their pictures, journals, or notebooks and other people can check it out and learn about those people. Then, it goes to the 1990s when a mom dying of cancer goes on her final tour with her band. And then finally to the future, in an unknown time when the world is going blind and a scientist is trying to make a device that people can use to see other people’s dreams—à la Wim Wenders’s Until the End of the World—but all he’s seeing is the three novellas that came before, and he’s trying to figure out why he’s only seeing those three moments in time. Another weird multicharacter thing.