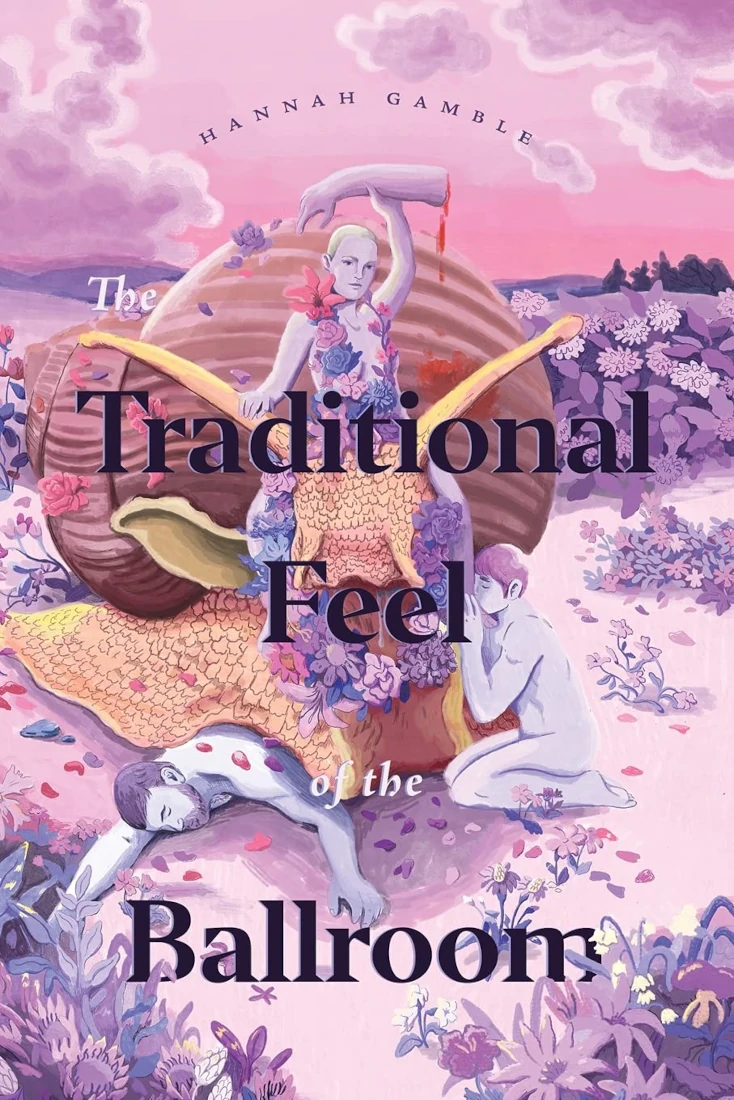

A Review of The Traditional Feel of the Ballroom by Hannah Gamble

Words By C.E. Janecek

Published June 30, 2021 by Trio House Press.

Hannah Gamble’s second poetry collection, The Traditional Feel of the Ballroom, never shies away from the violence of her themes, which address misogyny and rape culture. Her direct and often conversational tone makes the collection accessible to new readers of poetry—the speaker often pausing to explain her process, including her hopes and aims for a piece. The first poem in the collection establishes this rapport with the reader immediately:

I’ve wanted to give people

who come to see poetry a little something extra,

and me, blabbering, is all I’ve ever had

to give or to keep or to be with on my own.

There’s really very little art in that.

You’ll never hear me say it’s noble.

This delicate balance of egalitarianism and artistry does not always succeed, however. Certain sections of the book feel like there’s little room for trusting the reader in thinking critically about the collection’s themes. More experienced readers of poetry may feel frustrated, at first, as they wait for the collection to find its bearings. Later poems, however, dive delightfully into surrealism and extended metaphors that outshine the rest of the collection—a quiet sigh builds in my chest in the release at the end of Gamble’s poetry.

Many readers, myself included, will find themselves grappling with their own internalized misogyny while reading poems like “Always Given,” because Gamble never shields her readers from difficult themes.

I knew I couldn’t fight him off, or that even if I could,

there would be 5 others like him waiting.

I chose to welcome him, in my way.

Other women were nearby

so I wasn’t afraid.

He kissed my neck and I said “Oh, yeah,

people tend to like that.”

He bit my earlobe and I said “Oh, yeah,

goin’ for the ear.”

I was trying to be above him.

Above the doorway, above the street.

Above the other women who wouldn’t have

“handled it as well.”

Even as the speaker tries to “handle” the situation, she is looking at herself from a disassociated perspective, showing us how self-defense can appear like self-sacrifice. We see it from the women standing by, “grinning—in on the joke I was / trying to make of the man,” perfectly illustrating the way discomfort and powerlessness can only be met with a nervous grin, a fleeting grasp at controlling a situation. In the volta of the piece, the illusion of control shatters for the speaker: “Only upon seeing my friend’s face did I see that / I had been mistaken about what was the joke, / and who was the joke.” In these moments, the simplicity of Gamble’s writing brings these everyday occurrences into sharp clarity.

In other pieces, in which Gamble finds her poetic muse in the surreal, she allows an extended metaphor to express her themes, rather than the speaker’s direct reflections. In the poem “Growing a Bear,” she creates a keen contrast between whimsy and domestic decay:

You haven’t even considered how your wife will feel

when you have finished growing your bear. You could

write a letter to her tonight, explaining how your life

was so lacking in bear.

“Janet, it’s nothing you’ve done—

clearly you have no possible way of supplying me with a bear

or any of the activities I might be able to enjoy

after acquiring the bear.”

The bear is the elephant in the room, a sex life like beating a dead horse, an unexpressed middle-aged desire, a receding masculinity. The use of second person and passive voice adds to the dubiousness of this experiment and how the husband plans on explaining his needs within this marriage. The speaker is attempting to convince us of his need to fill the bear-shaped hole in his life, but the reader must extrapolate their own meaning out of the bear, the wife’s isolated nighttime routine, how friendships between adult men in suburbia wax and wane now that they are “past the age of college athletics, / most friends don’t even know what each other’s bodies / look like, flushed, tired, showering, cold.” This poem, alongside the curious bestiality of “The Queen,” evokes the ferality tucked in the guts of our patriarchal society. Gamble joins a tradition of poets using a persona to express the viciousness of girlhood and womanhood—the act of unmasking through the use of a mask—similar to Claudia Cortese’s Wasp Queen or Franny Choi’s Soft Science.

However, some poems unfortunately fall back on bioessentialism in their critique of rape culture as they illustrate the societal connotations of vaginas and penises. “The Sun and Open Air” and “Cabana” felt like they were over-simplifying that binary, making it difficult to parse what was tongue-in-cheek and what was meant earnestly—especially when the tone of the collection emphasizes directness. Other poems succeeded gloriously in their commentary because of their humor and specificity: “your dick would have rowed you through / the world like a paddle—[.]” While others felt like gross generalizations: “The man who, rejected . . . was biologically programmed to put things in” or a couple of stanzas later in the same poem: “if it weren’t for dicks, all vaginas would be naked at the seaside—always.” These lines rub me the wrong way—they stray from the specific moment and speaker, creating a synecdoche in which the vagina represents all of womanhood and dicks are “biologically programmed” to threaten anyone with a vagina.

These poems feel like they are doing a disservice to the collection as a whole and its mission to explore the nuances of rape culture. While every poet writes from their own experiences, when writing about sex-based violence, the writer should also consider how cisnormativity plays a role in moralizing genital metaphors.

The Traditional Feel of the Ballroom finds its place among narrative feminist poetry and is ideal for readers who are new to reading poetry and would feel intimidated by an experimental collection. The pieces inside highlight the everyday trials of being perceived as a woman in a misogynistic society and the ways it makes one rage and cry and sometimes just sit in quiet contemplation. The collection comes to an end as simply as it began, with the speaker’s earnest voice, “Now I don’t have to tell you / anything more about it.”