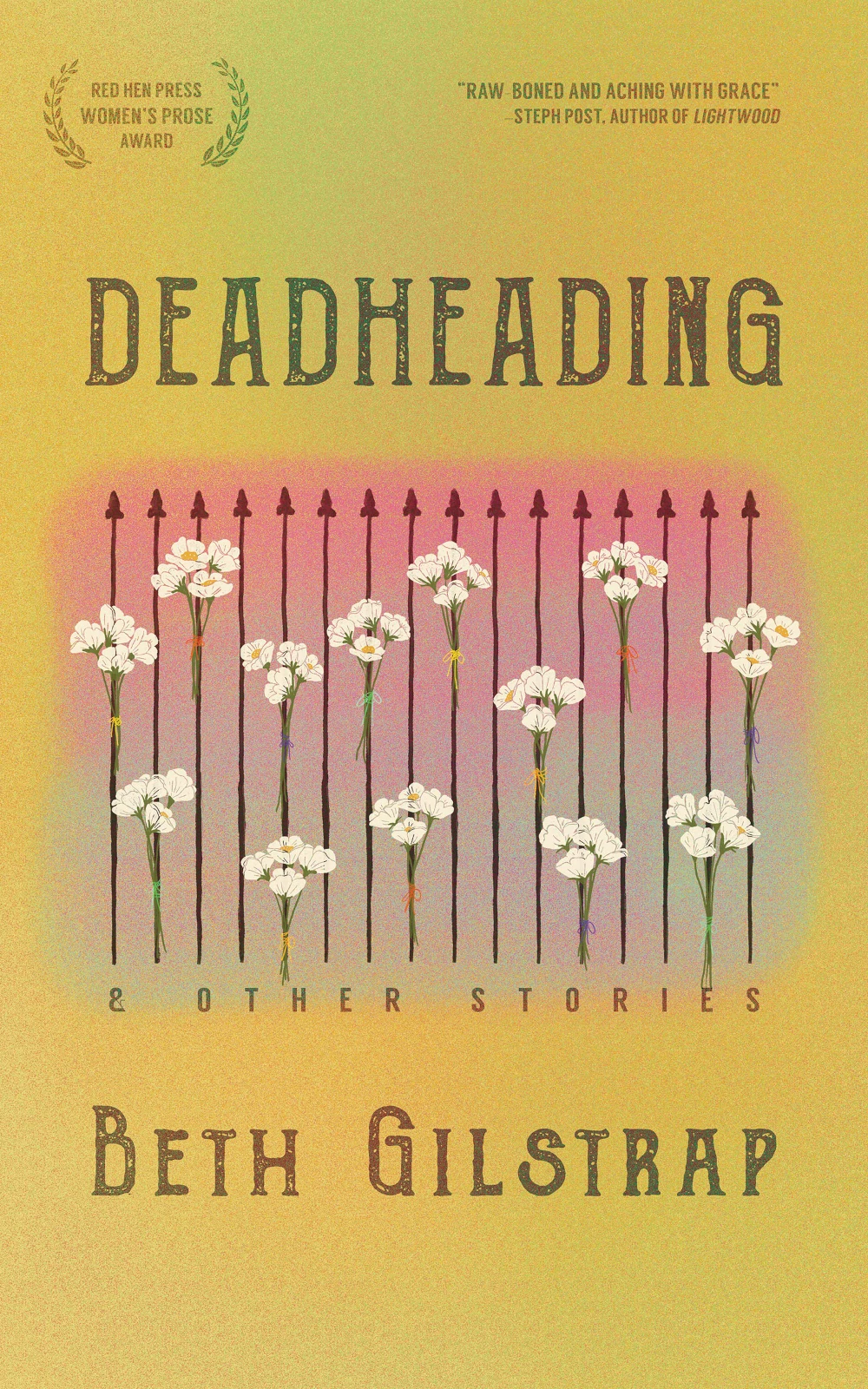

A Review of Deadheading and Other Stories by Beth Gilstrap

Words By Kaitlin Lounsberry

Published October 3, 2021 Red Hen Press

I wouldn’t consider these stories lighthearted. They sting and challenge perceptions, but it’s a large part of their charm. Beth Gilstrap’s latest short story collection, Deadheading and Other Stories, weaves together multifaceted, complex characters fighting to endure and find meaning in the mundane in the Carolina region of the US. In particular, it promises melancholy reflections of the work-classing with a special focus on its women and their attempts at survival.

I can’t claim to have much familiarity with the Carolinas. My knowledge of this region and its people extend to what’s taught in American history courses and media coverage of the last fifteen years. And while growing up in the Midwest doesn’t offer the same experiences as it would in the Carolinas, there’s something inherently universal about working-class small towns that transcend geographical differences. And Gilstrap captures that universal experience deftly and tenderly. There’s an element of soul-crushing heartache and yearning in this collection, especially in the stories that feature older couples living within the only environment they’ve ever known. Characters are so evidently unhappy but unable to make drastic life changes due to the socio-economic realities of this region. The “adults” in this collection exhibit a kind of acceptance you come to recognize from people just trying to get by.

The second piece in this collection, “The Denial Weeks,” is a perfect introduction to the worn-down adults who have worked their entire lives for a single company, only to discover they’ve been let go without notice or compensation. The repetition experienced by Paul and Imogen—married for decades and following the same routine for just as long—is suffocating to read. Yet, it’s reflective of a reality so many working-class adults experience. It reminds me of my own uncles who have gone into the same job every day, doing the same thing over and over, with the hopes of one day getting to slow down and enjoy a cold beer on the back porch. While more things transpire in their story, I felt most enchanted by the descriptions and the sensations experienced by this population without shame.

The stories that captivated me most, however, were the ones that featured teenagers and young adults. This age category, while still depressed about where they lived, maintained a degree of light and hope about their futures. Not yet beaten down or forced to make decisions for anyone but themselves, they continue to desire a life outside their town. Gilstrap wields their emotions to tap into often overlooked aspects of these towns and the people who inhabit them—that at one point they, too, dreamed of something more for themselves. Those complex emotions remind readers that they’re so much more than their jobs or where they live.

“Tomorrow or Tomorrow” was a story that had a particular note of longing and a search for meaning that sharply reminded me of certain experiences I had while living in my hometown. While drug use isn’t part of my own history, the loss of a classmate known since childhood—whether by suicide or accident—presented a certain kind of pondering I knew too well. Gilstrap captures the “whys” that seem to linger whenever someone young and bright dies effortlessly on the page. An important quality of the collection, especially for readers who might not be familiar with small, everyone-knows-everyone communities. As with “The Denial Weeks,” this story felt less about the action—though the try-hard cops and their soaring sense of self-importance highlights small-town law enforcement almost too well—than the feelings it evoked. But again, Gilstrap has figured out a way to weave moments of vulnerability with the hardness of her setting in a way that offers a unique perspective for her readers.

Obviously, I am a fan of this collection. If you’ve ever grown up in a small town where dreaming of more was met with scorn and rolled eyes, the desperation featured in this collection will resonate strongly. However, I do wish Gilstrap had included at least one story of someone who had gotten “out.” While I fell in love with each story and its characters for various reasons, as I neared the end it did start to feel like a slog being introduced to another set of characters and yearnings that felt similar to the ones that had come before. Getting out is as sensational in these towns as staying and it was an element that could have created a bit more variety and depth. Not only would it have added another layer to the stories, but I sincerely believe someone’s perspective of a town changes when they leave, and it would have been interesting to see Gilstrap include that viewpoint. This collection is a haunting telling of the Carolinas and their obsession with decay. And in many ways, it is a kind of ghost story, but it also felt a lot like a love letter to this region. Despite pinpointing its flaws and the strain this area has on its people, Deadheading and Other Stories is just as much a tender reflection of what it means to never quite settle.