Book Review: Four-Legged Girl by Diane Seuss

Words By Leah Scott

Please note that this interview was originally published on our old website in 2015, before our parent nonprofit—then called Tethered by Letters (TBL)—had rebranded as Brink Literacy Project. In the interests of accuracy we have retained the original wording of the interview.

If my creative writing studies taught me anything, it is that good poetry is a bodily experience. Good poetry resonates, echoes in the head and bones, vibrates the cells with its music. Diane Seuss’s most recent collection, Four-Legged Girl, encapsulates this physicality of language in a truly delicious way—it’s been days since I first read it, and still I feel it ricochet across my ribs when I pause to recall its splendor, its indulgent and celebratory sound.

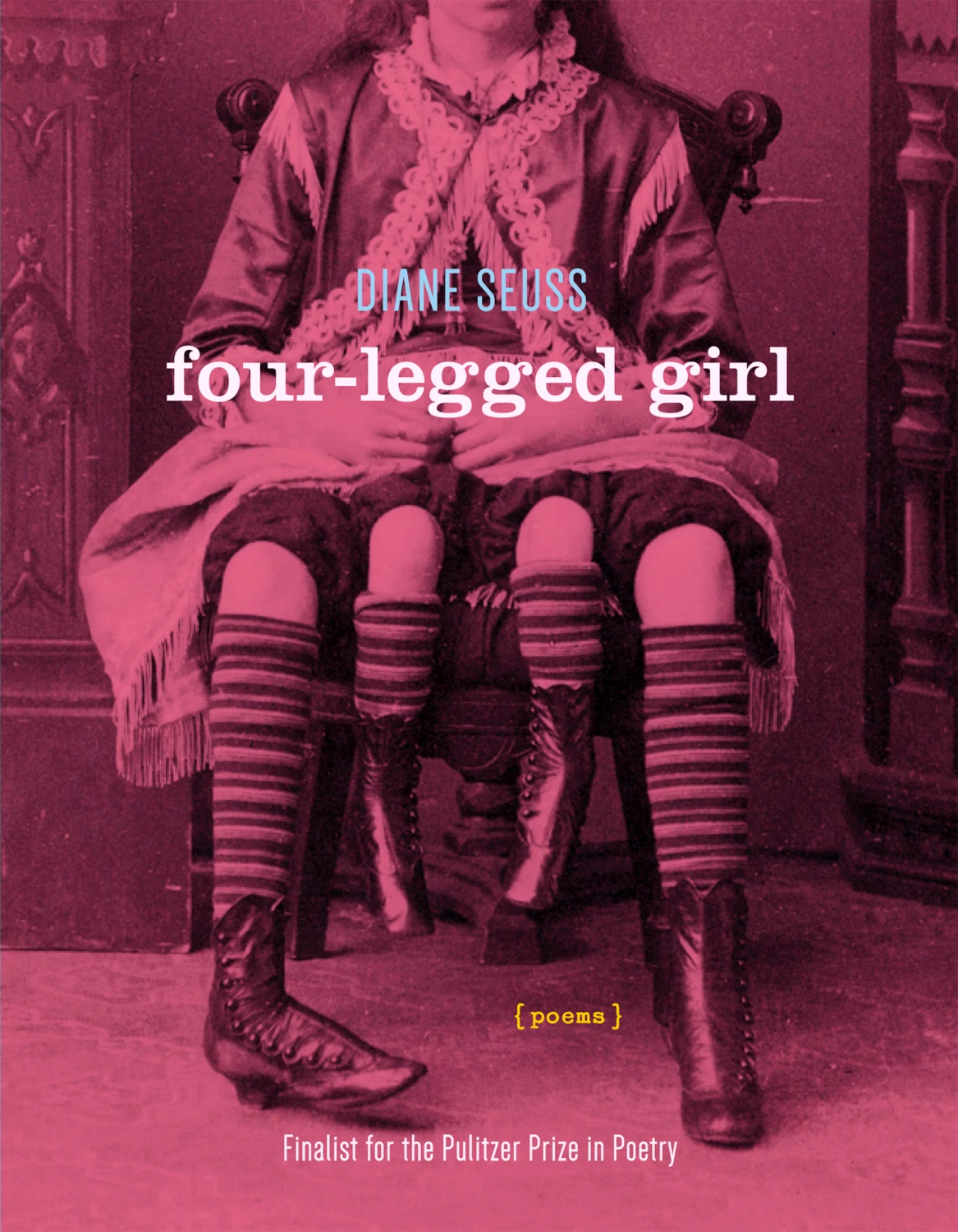

Titled in honor of Myrtle Corbin, a Victorian-era girl born with two sets of legs, a pair of pelvises, and two female reproductive systems, Four-Legged Girl unfolds as a hallowed chronicle of the body, illuminating notions of beauty and monstrosity, ecstasy and decay. Seuss illustrates the many incarnations of ‘body:’ body as human, body as nature, body as object, placing her conceptions of ‘self’ amid a rich depiction of multilayered experience. Her exploration of pastoral and urban imagery ponders how the body relates to its setting. The recurring appearances of the speaker’s father—who would “walk in the rain like his tumors were made / of sugar”— and ex-lover, “arms constellated with needle marks,” posit how a body engages with other bodies, both living and dead. This work contemplates what multitudes a single body might contain. In the poem “I once fought the idea of the body as artifact,” Seuss conflates the human body with the personification of things:

. . . His hair sticking up in small flames

like the choir-boy candles we dragged out of the mausoleum each December,

their wax mouths holding a pure note for decades.

. . . I cut bangs with pinking shears

and hardened my bob with Dippity-Do, my eyelashes fixed into black points

like the minute hand on my dead father’s watch.

At this junction of organic and inorganic, Seuss cultivates a metaphorical sense of interconnectivity and reciprocity. This duality permeates the entire work, expertly manifesting in her deftly-chosen diction and the many lives that it contains.

The book is divided into five sections, creating a somewhat chronological sense of how the speaker’s thoughts and views shift over time. As the sequence progresses, the concept of memory begins to emerge, indicating how time changes one’s perception of self—one’s body, of course, included. The title of the poem “Long, long ago I used to smoke in bed” immediately conjures a sense of past-gazing, and it proceeds to introduce one of the speaker’s younger selves:

I was beautiful, yes I was. Not so much beautiful

to the world. I was too short and round for that,

my ankles too thick, like a peasant’s. Working-class

teeth. Working class hand-me-down bras.

But beautiful to myself, yes, yes, and to some,

striking enough to be desired.

This version of the speaker describes the barren basement where she once lived. A gloomy place with a wall-bound bed, she indulged herself in garish jewelry and cigarettes and a single red, swaybacked chair. As in many of the poems, an ambiance of sparsity is conjured only to be countered by certain visions of luxury—yet these visions of luxury are essential to understanding the gauntness of the space in which the speaker finds herself. Her jewels sparkle all the more in that shadowy basement bedroom; her body is more desirable in that working class hand-me-down bra. This weaving of decadent imagery with a sense of darkness and dankness—the lushness of a red velour chair placed in an otherwise empty basement—is but one example of the striking dichotomies peppered throughout the book. The music of the language is so palpable and resplendent that it seems essential to somehow neutralize those synesthetic effects of such descriptive rapture.

Seuss possesses a true magic in her ability to show the inextricable link between luxury and decrepitude. She employs sumptuous botanical language to encompass life and beauty, uniquely using the oft-cliche flower as an original symbol for sex and youth. She presents death in all its melancholy, yet frames it in a generative, nourishing context: “a death bed / pomegranate;” “the poisoned strawberries, so sweet;” the air lush with ghosts; “the eight-point buck . . . through the windshield / of a fern-green car;” the euphoric, ecstatic final moments of a depraved addict. She offers a series of paradoxes in infinite form—a body of limitless mutation, calibrated by the gorgeous and the gory.

Four-Legged Girl is a vibrant gift to the senses. Each poem provokes emotion without sentimentality, igniting deep and resonant feelings of kinship, nostalgia, and understanding. The work as a whole offers balance, symbiosis: an exposure of the many paradoxes that underlie perception. It is the ultimate exhibition of being human. These are poems that will ring the human body like a chapel bell for generations.