Bookmarks, Pulp Fiction, Paved Roads & Lovecraft Country

Words By Dominic Loise

Not having a hometown bookstore growing up, I always pull the car over to hit the local independent bookstores when traveling as an adult. I turn a deaf ear to the repeated question of travel companions asking, “Aren’t all bookstores the same?” Whether the city is big or small, I’ve found that bookstores capture the identity of a place and diverse books on their shelves have the power to open worlds. Browsing the shelves of a local bookstore may reveal the close-mindedness of residential views in a town and whether a reader needs to travel to other cities to find their book nook. Once working as a bookseller in Chicago, I even saw a young woman from out of town moved to tears in our bookstore, struck by a sense of belonging caused by seeing her own identities and experiences reflected in books before her. So, to answer my travel companions of the past: No, not all bookstores are the same, and that is a wonderful thing.

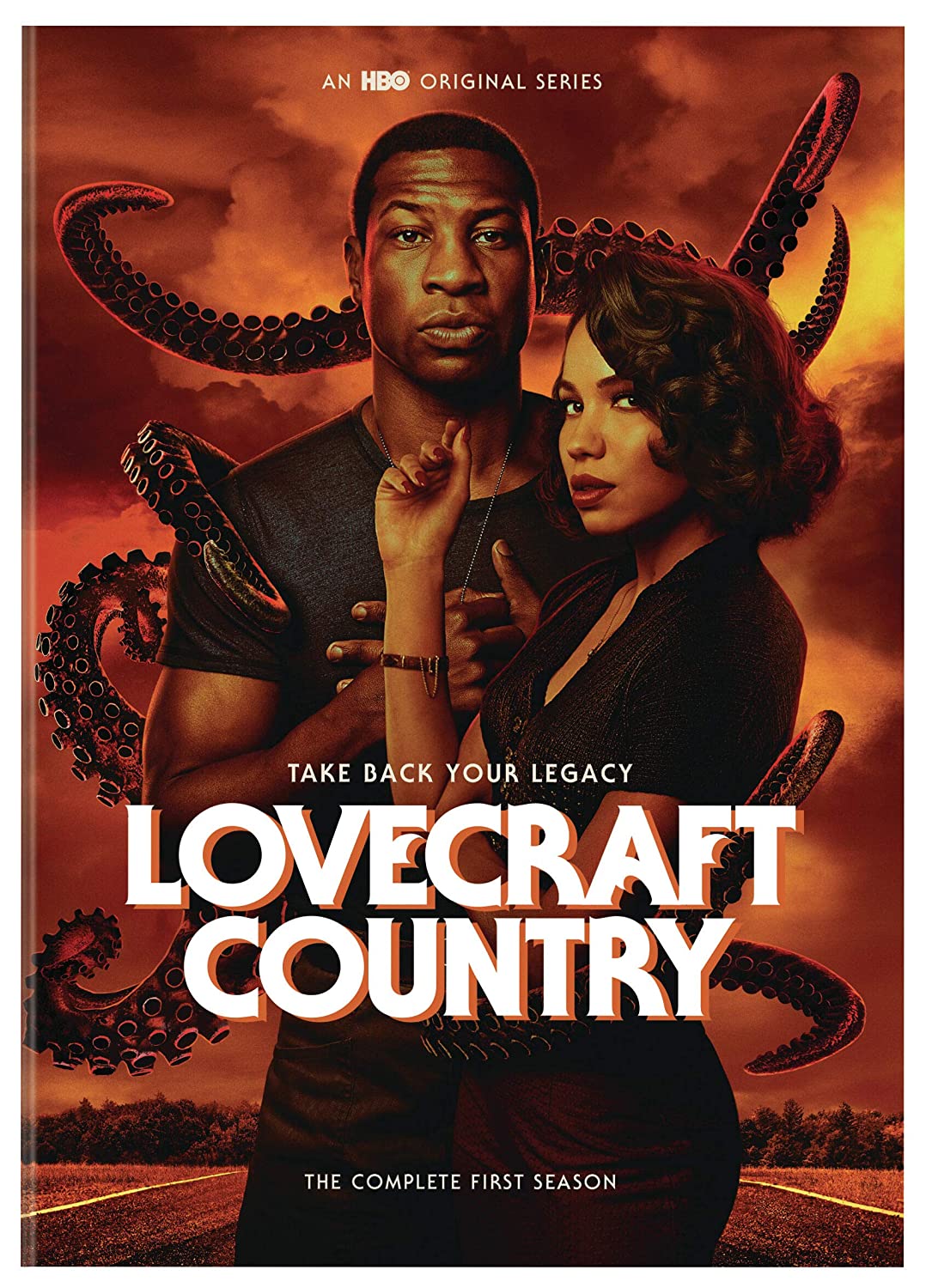

One of my favorite bookstores is Giovanni’s Room in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (now Philly AIDS Thrift @ Giovanni’s Room). This bookstore is not only the oldest LGBTQ bookstore in the United States but is named after the James Baldwin novel of the same name. Both the store and the novel place identity at the forefront of their mission, as Baldwin’s novel was about a man finding himself in Paris, mirroring Baldwin’s own journey of self-discovery as a gay black man. When Baldwin came back to an America caught in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, his words would help many find their own sense of identity, a legacy they still carry, continuing to influence the idea of self-exploration in modern media. The HBO Max show Lovecraft Country is a great example of this legacy as it uses a James Baldwin speech in Episode One to not only illustrate the racism that the characters experience but to emphasize the central theme of identity in the show. And so I’ve found myself looking at how Lovecraft Country drives through its antiquated pulp novel inspiration and onto new highways, uplifting diverse voices within speculative fiction and developing into Afrofuturism.

Books from our past inspire Season One of Lovecraft Country, both the shared fantasies found on wire spinner racks and those that explore the unknown. The series—based on the Matt Ruff novel of the same name—features a cast of black characters and deals with forbidden magic, white supremacy, and stories both pulped and personal. The show draws inspiration from the writings of H.P. Lovecraft and Jules Verne and sets itself in 1950s America, where Jim Crow laws segregated much of the country. It is in this setting that Lovecraft Country draws its most important inspiration from another book: The Green Book, an annual guidebook for black motorists by Victor Hugo Green, published from 1936 to 1966. In the show, the characters travel across the country on a mission to publish their version of the book, researching safe establishments for black travelers. The map of any black motorist traveling through “sundown towns” in Jim Crow America could read “Here Be Monsters,” as depicted in the show’s first episode, “Sundown.” A sundown town was a segregated municipality that did not allow for any non-white residents; if your business in town was not done come sundown, your safety was not guaranteed. Lovecraft Country captures the anxiety incited by these laws, showing us the characters in peril, driving to reach the county border before sunset without speeding as the racist sheriff—looking for any excuse to pull them over—follows closely behind them. The purpose of The Green Book was to find a safe haven from this monster of racism in America. Just as the content of the fiction books that Lovecraft Country is pulling from as source material is not just their use of monsters, magic, and mayhem, but to show that by blending the fantastical with the factual, we forge a roadmap from mindsets of the past. A better identity for the genre has now unfolded, with modern work opening up into diverse narratives, like those found in Afrofuturism. Afrofuturism is about collecting the images of African diaspora culture to rocket them forward into a high tech, science fiction setting (as seen in the blockbuster success of Black Panther), as opposed to carrying on the traditional space colonization path from the pulp magazine days of science fiction and fantasy in the 1950s. Spoiler Alert: In talking about how Lovecraft Country links to Afrofuturism within this essay, you find some surprises from Season One spoilt, for anyone who hasn’t first watched the show.

The most overt fantastical inspiration for Lovecraft Country is contained within the show’s title, which links it to the writing of H.P. Lovecraft (1890–1937). Lovecraft’s work brings to the show the ideas of warlocks, elder gods, and unnamable horrors but also racial influences beyond The Green Book, as it is through the use of Lovecraft’s work that a direct examination of racism comes into play. It is here that I would mention that H.P. Lovecraft was an amateur journalist and self-published The Conservative, which touted his personal anti-immigration and pro-segregation views. Even with his problematic politics, Lovecraft saw power in books (they are a source of magic in his works), and the theme of identity is central to his writing. The key difference between Lovecraft Country and H.P. Lovecraft being that loss of identity is the notion behind Lovecraftian Horror. When “man” confronts a cosmic terror that he cannot understand, he is inevitably driven to the brink of madness; Lovecraft’s work is about man not being able to be at the center of his own universe.

We see the differences in the theme of identity between this pulp inspiration and the television show best when comparing Episode Five, “Strange Case,”to Lovecraft’s story “The Thing on the Doorstep” (1937). In “Strange Case,” the character of Ruby, played by Wunmi Mosaku, wakes up as a white woman after sleeping with a white man, who turns out to be a sorcerer. This episode examines white supremacy and racism in one of its most systemic forms as Ruby uses her new body to get the job she’d always wanted at the downtown department store. Ruby not only gets the job she has repeatedly been turned down for because she was black, but in this new body, she even becomes a manager. In “The Thing on the Doorstep,” the story’s execution is more about Edward Pickman Derby, a male student of the dark arts, being rendered powerless as his wife switches minds with him because “a man’s mind is superior” for certain rituals. Witnessing magic and seeing how small they really are in the universe drives Edward mad in the end; Edward came to magic for the power but can’t deal with the changes that come with it. But Ruby comes into her own through her experience: she faces something bigger than herself—in this case, magic—and to not be limited by the society around her, she uses it. Ruby’s story eventually shows us that she doesn’t need the false self to be at her most powerful. Ruby’s true power comes in learning how to stand firmly in her own form, whereas Edward cannot stand powerfully in his own form alone, and it is up to others to use that form where he is unable. What Lovecraft Country shows us is the power of personal growth and coming to know oneself, regardless of the bigotry of others. The show grows beyond its source material through its characters finding inner strength and growth when facing the cosmic unknown. In juxtaposition, Lovecraft’s writing remains centered on a fear of the growing unknown, haunted by his politics and evident in his treatment of identity.

Lovecraft Country also sees inspiration in the work of Jules Verne (1828–1905). Jules Verne, along with writers like H.G. Wells, established what we know today as the genre of science fiction in the late 1800s. The Verne novel that inspires the characters to dig deeper into identity in Lovecraft Country is Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864). Journey to the Center of the Earth is the story of a professor and his nephew coming across ancient runic instructions that tell of a pathway to our planet’s core. The journey takes them across Europe, down a volcano, and into a pocket prehistoric world lost to time. We see Journey to the Center of the Earth as inspiration in the show not only with the uncle/nephew mentorship between George and Atticus Freeman, played by Courtney B. Vance and Jonathan Majors, but in the deciphering of runes, this time of a magical origin. And just as in Verne’s book, the characters spend time researching, logging hours in the library, and learning by “reading a damn book” as stated by Atticus’s father, Montrose Freeman, played by Michael Kenneth Williams. In Episode Four, “A History of Violence,” we see the characters taking that research and exploring underground tunnels beneath a museum that is full of deathtraps. When the characters go underground, they are free from the confines of the racism living above them and we see them in full adventure hero form. The inspiration of Verne’s work is not something for the characters to overcome, as with Lovecraft’s work, but for them to embrace.

Verne didn’t see himself as a science fiction or speculative fiction writer, but as a “probable” fiction writer. His work would go on to give future generations inspiration and hope for future discoveries and adventures. For example, his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon told the story of an inventor that shot a projectile off from Florida, not unlike the first manned Apollo rocket launched in 1968. Through Verne, we identify with the wonder of our world becoming smaller, travel becoming quicker, and a celebration of scientific achievements that unite us all. Probable fiction is a precursor to the hope and change we look towards in the future, such as what can be found in the diverse works of Afrofuturism.

Season one of Lovecraft Country uses dime magazine time travel stories of the 1950s to best illustrate characters finding their identity and in doing so, takes the show beyond its pulp inspirations into the empowerment of Afrofuturism. The theories and practices behind Afrofuturism become the secret weapon for the Freeman family in Lovecraft Country. The main character of Atticus Freeman goes from reading and dreaming of pulp heroes in the show’s opening to becoming the mysterious stranger memorialized in family stories, and through time travel, rescuing younger versions of his father and uncle during the Tulsa race massacre of 1921. Episode Seven, “I Am”, takes the concept of travel and identity one giant leap forward. In it, the character of Hippolyta, played by Aunjanue Ellis, time travels to become whomever she wants to be in history, with her first stop being 1920s Paris to meet Josephine Baker. She travels to many time periods and lives many personas, but eventually learns to live as herself, gaining the courage to confront the obstacles of her own time: only after traveling through time and coming into her own can she tell her husband, George Freeman, how he has always seen her as a wife and not an equal partner. Hippolyta faces vast cosmic uncertainty but is never driven to fear by the unknown—in fact, she finds her identity and name through it. The final image of the series Lovecraft Country is symbolic of this Afrofuturisistic triumph over adversity, crafted with the future technology from Hippolyta’s time travels, standing victoriously over pinned and defeated Lovecraftian wizardry.

For an onramp to read more Afrofuturism and build your library of diverse voices in the speculative fiction genre, I would say How Long ‘til Black Future Month by N. K. Jemisin is as good a place on the map to start as any. I also mention N.K. Jemisin because of how her record-breaking, three-time Hugo Award-winning Broken Earth series represents a time in the Hugo Award voting when a right-wing group called “Sad Puppies” was campaigning against diversity in the genre. The argument Sad Puppies gave for their campaign was that older guard writers who had “put their dues in” were being sidestepped by newer writers. Some of the writers they mentioned as examples more deserving of a Hugo were writers who tended to write more in the vein of classic pulp fiction writers, a genre historically represented by white men. I will make my point on the whole matter by quoting James Baldwin from a letter to his nephew, “My Dungeon Shook:”

“ . . . the danger, in the minds of most white Americans, is the loss of their identity. Try to imagine how you would feel if you woke up one morning to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame . . . Any upheaval in the universe is terrifying because it so profoundly attacks one’s sense of own reality.”

James Baldwin traveled and lived in Paris for a time to find himself before coming back to the United States and inspiring the Civil Rights Movement with his writing. Like Verne’s work in probable fiction and Baldwin’s work in identity-centered narratives, Afrofuturism is a beacon and a road sign letting individual readers know that there is room for everyone when they arrive home from their travels the long way around and that it is possible to envision a better future. Lovecraft Country shows us throughout the season how there is power in owning our personal journeys and finding hope in books, especially those that embolden us to pave new roads for ourselves and those after us. Books that move the reader forward can inspire those who put the first footprint on the moon or a foot forward when marching for civil rights. And, as we’ve seen, they can even provide a pathway toward self-discovery. Just as a bookstore can be a chain catering to consistency or an independently designed warm welcome, allowing any and all travelers to find a place on the shelves. Come inside with me and cast away the unknown, or—to borrow from Lovecraft Country’s Montrose Freeman—“Read a damn book.”