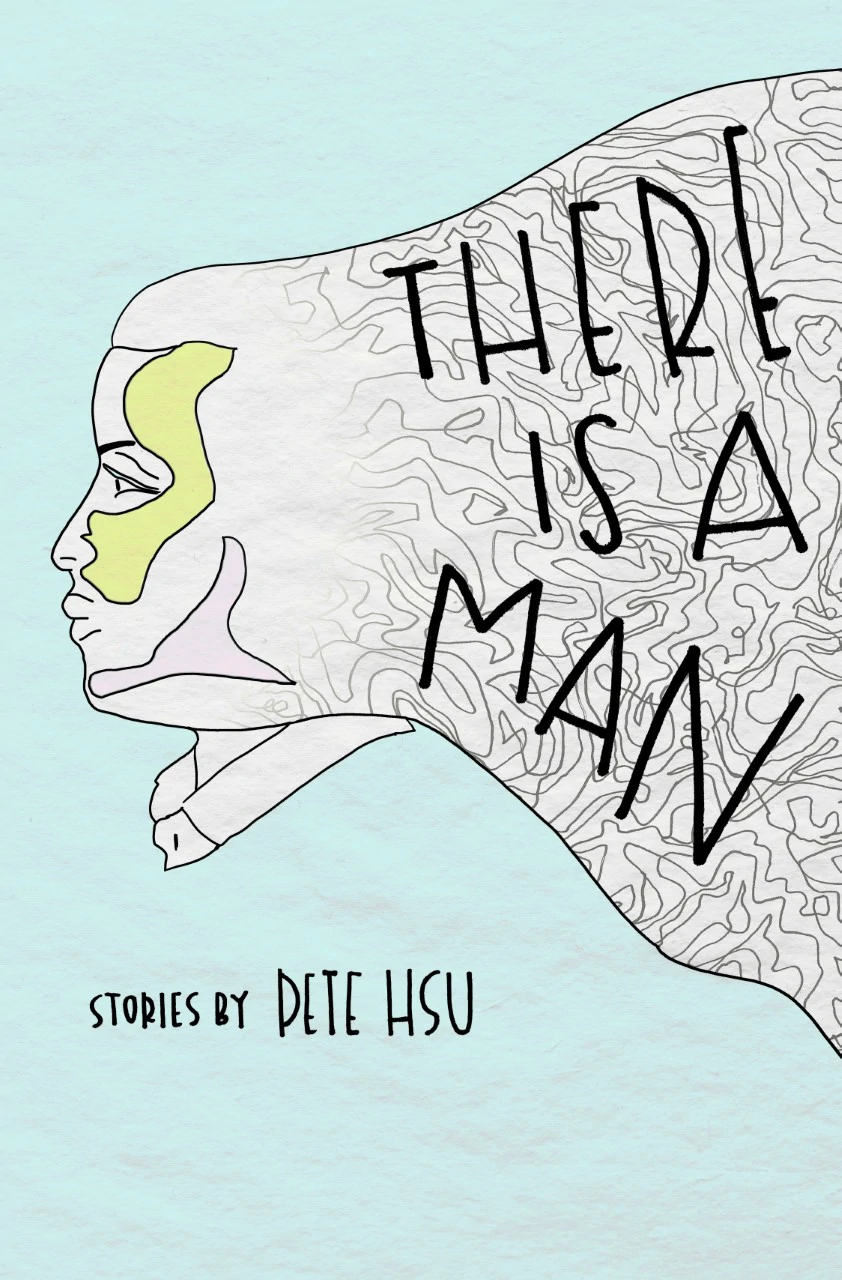

A Review of There is a Man by Pete Hsu

Words By Jaclyn Morken

Published on January 12, 2021 by Tolsun Books

Sharp and ingeniously layered. That is, quite simply, how I would summarize Pete Hsu’s arresting debut, There is a Man. The three short stories in this fiction chapbook experiment with narrative style and structure in ways I have never experienced before, bringing such a subtle yet powerful dynamic to the whole work.

The chapbook opens with “Asleep for Days.” At once absurd and painfully relevant, it depicts a world in which “everyone has a gun” and is eager to use it at any provocation—from short-tempered adults to literal infants. “The Lovecats” then tells a story of tragedy through a series of sections, labeled as numbered “examples,” each one laid out with the dispassionate style of a textbook physics problem. And finally, “Mission Concept” shows us the consequences of sacrificing family relationships for long-distance work.

“There is a man,” as each story opens. He is the reckless driver who aggravates our first narrator into a shootout. He is the lone figure on the ledge of a hotel rooftop. He is an astronaut and a distant father working in trade. He is different in each encounter.

There is something methodical in the structure of all these stories, and the narrative progression is always anything but straightforward. The first two stories, organized into a series of days and examples respectively, build suspense and intrigue as each successive section adds more complexity and context to the opening premise. “Asleep for Days,” for instance, follows a series of unnamed narrators over the course of eight days, during which the feeling that they are entitled to use violence over the slightest inconveniences leads to increasingly sobering confrontations across the nation, creating a powerful satire on gun use and possession. The chapbook’s final story, “Mission Concept,” is structured slightly differently but it is no less striking, opening with a sweeping frame narrative that then narrows down to a single family and their problems. The emotional toll of the father’s work is palpable in juxtaposition with the ever-distant “astronaut.”

Though the details of the characters and settings are often sparse, Hsu nevertheless achieves remarkable poignancy and emotion in these stories. “The Lovecats” is my personal favorite. The first section, “Example 1,” sets the somber tone of the rest of the piece: the protagonist is standing on the ledge of the hotel roof that he visited with a close friend before her death. Each subsequent example begins similarly but then adds a little more context, as if the narrator is attempting to re-explain a difficult problem—or methodically rationalize and process the trauma of his friend’s death—over and over again. Each character comes into being slowly but starkly, and by the time we come to understand the hints folded throughout, the ending is all the more gutting.

What is most fascinating about these stories is not what they are about, but rather how they are told. Hsu’s words are straightforward and his descriptions short and factual, so much so that at first I thought the narrative style would be off-putting, too distant to resonate. Perhaps it would have been, had Hsu not accompanied this narrative style with such effective layering that it becomes one of the greatest strengths of this chapbook. Hsu writes with a masterful command of the narrative voice, each word intentional and restrained—the perfect example of “show, don’t tell.”