Fibs and Wiggles: An Interview with Dan Josefson

Words By Dani Hedlund

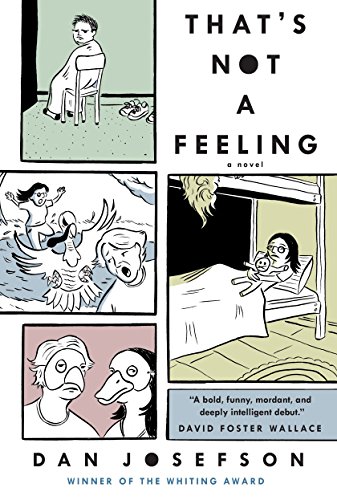

Dan Josefson’s debut novel, That’s Not a Feeling, is an unsettling book. Set in Roaring Orchards School for Troubled Teens, the novel forces us to navigate a murky world of disorder, one without objectivity, clear-cut heroes and villains, or even a reliable narrator. The characters—students and staff alike—are deeply damaged, often comically so, and the school meant to heal them seems much more likely to deepen their issues. With a Catch-22-eque flare for satire, punishments and prizes are handed out with no perceivable logic, “therapeutic methods” seem more like torture than treatment, and the strange rules that control the school are so absurd the reader—and the characters—can only laugh.

In this world of chaos, it seems only fitting that our narrator, too, would be unstable. After two attempts to commit suicide, Benjamin’s parents send him to Roaring Orchard, but, compared to the other students and teachers, his troubles seem insignificant. If anything, Benjamin tries to act more damaged, just to fit in. However, what is most unique about Benjamin is not his past, but the way he chooses to narrate it. Throughout the novel, he is so impressionable and timid that his voice comes across as a distanced, third-person narrative. We don’t even realize that Benjamin is telling his story until a sudden emergence of “I” slices into the text. What is even more troubling is that Benjamin often narrates events, feelings, and thoughts he could not possibly know, showing us early on that we cannot trust everything he tells us.

Our narrator is not the only character we are hesitant to trust. His closet friend—and eventual love interest—Tidbit, is a chronic liar; the headmaster, Aubrey, could easily be branded as a deranged egomaniac; and half the students and staff are utterly delusional. These elements create a plot that often has us laughing, shaking our heads at the ridiculousness of the situation our characters find themselves in. However, just like in Catch-22, there are also troubling moments when we recognize that these sorts of things actually happen, where our humor hardens in the realization that we are laughing at ourselves, at insecurities, fears, and hopes that reside in all of us.

It is without hesitation that Tethered by Letters recommends That’s Not a Feeling. Not only is this novel a humorous narrative adventure, it’s also deeply moving, subtle in its approach, and beautiful in its execution. Roaring Orchards might be a world without objectivity, without clearly defined lines and roles, but sans those limits, Josefson has painted a vivid portrait of human frailly and perseverance, one that makes us question what breaks us, what heals us, and what makes that journey worth it.

Josefson on That’s Not a Feeling

One of the most unique aspects of That’s Not a Feeling is the setting, Roaring Orchard School for Troubled Teens. At first glance, the school is a strictly organized institution, run so efficiently that both the teachers and students exist in a soft equilibrium. However, as we delve further into that world, we realized that if there is equilibrium, it is a deranged one, if it is organized, that system is built on chaos.

When I asked Josefson where the inspiration for this setting arose, he explained that he had once worked at a similar institution. Fascinated by the conflicting elements at play—especially ideas of authority—Josefson wanted to create a similar “dystopian” world with Roaring Orchard. This setting also presented him with the perfect mixture of serious and hilarious, where he could write about characters confronting their inner demons with a good does of contradictions and absurdities thrown in to lighten the mood.

At the root of Roaring Orchards is Aubrey, the headmaster. Although Josefson stated that he constructed this character to uphold many of the “classic villain characteristics,” he also wanted him to be just as convoluted as the school he runs. At times ruthless, at others shockingly caring, Aubrey is the force that keeps Roaring Orchard functioning, if not functioning chaotically—which seems to be the way he likes it.

Because there is nothing black and white in the world of That’s Not a Feeling, it seems only appropriate that the narrative too denies the reader any sense of objectivity. Pulling on traditional ideas of the unreliable narrator, Josefson explained that he wanted there to be doubt in the readers’ mind as to the validity of what was being reported. Josefson achieves this by having his first-person narrator, Benjamin, narrate moments, feelings, and thoughts he could not possibly know. When I asked Josefson about this fascinating technique, he explained that he didn’t always have Benjamin masquerading as a third-person narrator. Instead, in the first draft, the story was told purely through an omnipotent third-person. It wasn’t until the revisions that he started to consider books like A Sport and a Pastime by James Salter, where the first-person narrator essentially pretends to be a distanced, objective narrator, only to reveal suddenly that he is in fact one of the characters.

Although the “sneakiness” of this interested Josefson, the way the style reflected Benjamin’s personality was the real appeal. “Benjamin’s personality is really like a blank slate since he is so self-effacing,” he explained. As a result of his timidity, his narration is almost completely void of personal opinions, giving the illusion that he is the distanced third-person narrator he appears to be. Only in moments when he directly refers to himself—usually from the perspective of the present moment when he is writing his story—do we get any feel for Benjamin as a person. However, these moments are so rare that, even hundreds of pages into the novel, they still shock the reader.

Josefson on Writing and Publishing

Josefson started That’s Not a Feeling in 2001, while he was studying for his MFA at the University of Nevada. When I asked him to explain his general process, he told me that he started writing the novel in the middle—with the escape from the school—not realizing it would in fact be the moment that closes the book. Following this pattern, Josefson didn’t write the chapters in order of sequence. Instead, he’d write whatever moment inspired him and then went back afterward and pieced these scenes together, creating an outline and conforming the sections to it. Of course, this meant that he had to do a great deal of cutting and adding filler sections. Laughing, Josefson confessed that “it wasn’t very efficient,” but, in the end, he’d pieced everything together just right…even if it took him six years.

Once he completed the novel in 2008—using an early version of the draft as his thesis for his MFA—he began the arduous hunt for representation. He wrote his query letters, he polished his chapters, he sent them out to every agent he could find…and nothing. Then he started targeting smaller presses, with the same result. It wasn’t until 2011, when an intern at Soho press pulled his chapters out of the slush pile, that his dreams of publication finally came to fruition. His editor, Mark Doten, quickly discovered just how unique and brilliant That’s Not a Feeling is and, a year later, Soho published Josefson’s debut novel.

Hearing this incredible story, my first question was simply how he survived it, how he never lost hope. Smiling humbly, Josefson told me about how supportive his friends, teachers, and other writers had been of the novel, how this helped him weather the sea of rejection. Starting a new novel, he added, also aided him greatly while he marketed That’s Not a Feeling, allowing him to keep his focus on his craft.

When I asked him if he ever considered giving up on his first novel, shaving it in drawer somewhere and focusing on the next one—as many writers have done—he shook his head. “I felt like I had to get it out there,” he replied.

Even with a publisher backing him, he was still one step away from “getting it out there;” he still needed to work with his editor at Soho. The two major issues were balancing so many characters and speeding up the first fifty to eighty pages. In this aspect, Josefson felt exceptionally blessed. He gushed about how wonderful his editor is and how helpful he was when they tackled these issues.

As the interview drew to a close, I asked—as I always do—if Josefson had any advice for our many aspiring writers at TBL. Reflecting on his own experiences, he advised that once you complete a manuscript, “don’t limit yourself to the big guys…do everything: agents, little presses, journals that will publish your chapters.” He spoke at length about small presses and literary journals, how smart and inspiring the people who work there are—he was talking about TBL, right?—and how much better his hunt for publication became when he made this switch, not only because Soho eventually published his novel, but because he was able to interact with young, inventive, and passionate people that reminded him of why his novel was worth fighting for.

Excerpt from That’s Not a Feeling

Tidbit crawled into a spot large enough for her to lie down, between the stems of two bushes whose branches had grown into one another overhead. She could see the Mansion’s front lawn and the valley beyond it. The sun hung over the hills, dripping heat. A brown Oldsmobile Cutlass she didn’t recognize was driving up the school’s gravel driveway, making a buzzing sound.

It was parked in the carport next to the Mansion, facing the girls. A scream escaped it as a door opened and a woman climbed out, and was silenced when she swung the door shut. New Girls stopped what they were doing to look out across campus at the car. The scream erupted again as another door opened. A man exited the driver’s seat slowly and again, like in a cartoon, the scream was gone when he closed the door. The couple climbed the front steps and, after taking one long look back, entered the Mansion. It was an intake.

Tidbit couldn’t tell whether she heard muffled screaming still coming from inside the Cutlass. Another dazzling wave of energy was seeping through her. She stared at her hand drawing circles in the dust. Tidbit used to tell me how much she hated her hands. Except for the bloody bits where she bit them, they were completely pale, even at the end of the summer. Worse, they were so swollen that her knuckles just looked like dimples, and they trembled from the Lithium. It was what it did to her hands that made Tidbit want of get off the Lithium. But Dr. Walt always said maybe.

Tidbit turned to see Carly Sibbons-Dias crawling toward her in the narrow space between the wall of the Classroom Building and the back of the shrubs. Carly squeeze into Tidbit’s space beneath the junipers and collapsed next to her.

“Hi, Tidbit,” she said. “Found the razor?”

“Nope.” At home Carly had worn her hair dyed black, but no one at school was allowed to use dye, so in the weeks since her intake, her blond roots had begun to show in the thick stripe down the center of her scalp where she parted her hair. Everyone said it made her look like a skunk but up close, Tidbit thought, it didn’t really. “How’re you feeling?”

“Okay.”

“Anything yet?”

“Nah. You?”

“My vision’s kinda messed up,” Tidbit said. “I keep seeing tiny, tiny little blackbirds hopping from branch to branch in these bushes, but when I look they’re not there.” This wasn’t exactly true, but when she said it, it felt sort of true. “You see anything like that?”

Carly just sighed and looked where Tidbit was looking, at the brown Cutlass by the Mansion. She thought she saw a silhouette move inside it. Carly edged forward so she could see the car better. Maybe the Dexedrine was messing with her vision. “You think Bev just took the razor blade?” she asked. “Is she a cutter?”

“Everyone’s a cutter,” Tidbit said. “Have you seen her belly?”

“Did she do that to herself?” Carly spat in the dirt. “Shit. She didn’t do that with a razor, do—”

Tidbit help up her hand to quiet Carly.

She heard something from inside the car now, a distant wailing. There was thud, then another, a banging that was getting louder and slowly gaining speed. The sunlight reflecting off the windshield trembled with each thud, and with each Tidbit could just make out the sole of a shoe hitting the inside of the glass. Then two soles, kicking the windshield together until the shatter-proof glass began to spiderweb. Finally the kicking became bicycling, one foot after the other. The girls could hear the screaming with perfect clarity as two grey-green sneakers kicked the crumpled window away.

After a few moments, a group of staff members and Regular Kids ran out of the Mansion. They opened the front doors of the car, which I hadn’t bothered to lock, dragged me from my parents’ car and held me down on the ground until I stopped yelling. It took five of them to hold me, though I’m not all that big. Then they led me up the Mansion steps and inside.

“Holy shit,” Carly said. “Finally something cool happens at this fucking place.”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” Tidbit said.