Finding Meaning in Defeat: An Interview with Jennifer DuBois

Words By Dani Hedlund

It’s 1979 and Alexandr has just moved to Leningrad, his love of chess guiding him through the frigid Russian city. He does not yet know that the cold will drive him into the warm embrace of political dissidence, that long after he’s become the World Chess Champion, he will fight against Putin for political office. He does not know that the death threats will become so overwhelming that his apartment will become a prison. Right now, he knows only that he is freezing, lonely, and might have made a mistake leaving home.

On the other side of the globe, twenty-seven years in the future, Irina has graduated from university, taken a post teaching, started a new romance. But she knows it will not last: just like her father, Huntington’s disease will claim her mind long before her body dies. She can only wait in dread for the involuntary flail that will mark the beginning of the end. However, unlike her father, she is determined to die on her own terms. When she discovers a letter he wrote to his favorite chess champion—asking how he progresses in a chess match he knows he will lose—setting out to track down the answers her father never learned seems like the best way to do just that.

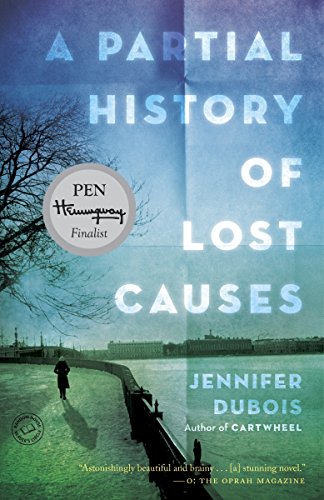

In an exciting world of political intrigue, vivid characters, and wild adventures, A Partial History of Lost Causes introduces us to two different characters, in two different times, both confronted with the certainty of death. As the story of Alexandr’s thirty-year rise to fame intertwines slowly with Irina’s journey to find him, Jennifer DuBois’s tale chronicles the Soviet Union’s breakdown, the evolution of the game of chess, and the battle still raging to free Russia of Putin’s reign. Yet this story is not only politically intriguing, for as we zoom in from the enormity of Russia’s history, we are shown the very personal struggles of the characters within, characters confronted with their mortality, with a desire to find love, with the desperate hope to finding meaning before it’s too late.

It is with great enthusiasm that Tethered by Letters recommends A Partial History of Lost Causes. Traversing space and time, this wonderful debut novel brings two broken strangers together, not to complete one another, but to share in their fragmentation, to embrace it. Although the rich history of Soviet Russia sets the backdrop, at its core, A Partial History of Lost Causes is about so much more than chess championships and political unrest. It’s a story about losing, about the choices you make when the checkmate is inevitable. Both Alexandr and Irina are marked for death, but with passion and grace, they strive to make that defeat meaningful, to find beauty in lost causes. It’s about certain defeat, of loss, of death: but more than anything, it’s about making that loss meaningful.

DuBois on A Partial History of Lost Causes

Given the incredible historical and philosophical depth of A Partial History of Lost Causes, I expected as the author a wizened history professor, jaded enough to write a book about lost causes, untimely deaths, and political corruption. Thus I was rather surprised when Miss DuBois, a beautiful young woman, sat before me for the interview. I was entranced by her adorable bobbed hairstyle and easy smile, wondering how a girl like that became ensnared by post-Soviet Russia and esoteric genetic diseases. After laughing off my incredulity, DuBois explained that she’d been fascinated by Russia ever since she visited there in the early nineties. Exploring these ideas in college, she became further obsessed with international politics and, in particular, post-Soviet states. However, what really inspired her to write about Russia was learning about Garry Kasparov, the real-life Soviet chess champion turned political dissident. “I just thought that would be a really interesting character arc. It seems like such an interesting story that caught my imagination enough for me to want to keep writing about it.”

As inspiration for Irina’s genetic disease, DuBois said that “my father had Alzheimer’s disease, so I grew up against the backdrop of a lot of grim questions about cognitive identity and what you do when you are in a situation you know is going to have a really bad outcome…I was really interested in that sort of dramatic situation. And I was drawn to Huntington’s disease because of its unique particularities. You know, you can get tested for it, and know when you are going to become ill, in a timeframe of a couple years, and that really matched the dramatic situation I was aiming for.”

After she decided to merge these two very different inspirations, the next battle was constructing narratives. Certainly one of the most interesting aspects of A Partial History of Lost Causes is DuBois’ choice to tell it through alternating voices. Not only did she choose to write two narratives spanning different timelines, but also two very stylistically different voices—Alexandr’s chapters are told in a loquacious third-person narration while Irina’s are narrated in the first-person with a very open and personable tone. When I asked DuBois about this choice, she explained that since Alexandr’s narrative is so much more expansive than Irina’s—“his plot spans thirty years and he has all these adventures and there’s the dissidence and chess champion life and post-Soviet life”—it made sense to write it in third-person. In contrast, Irina’s journey “is much more personal and only occupied a few years…So I think, from a writing standpoint, it seemed important to have hers to be in first-person because I think her story is essentially voice-driven by the force of her personality.”

I was curious to know DuBois which narrative she preferred. “I really liked writing in Irina’s voice,” she replied, “and, in a lot of ways, she was less of an imaginative leap for me…Although, in other ways, it was more difficult to conceptualize since she is dealing with a terminal disease.” On the other hand, although the character didn’t come to her as easily, she relished the plot turns that Alexandr’s story enabled. By fictionalizing Kasparov’s life DuBois was able to construct his plot around the markers of actual events. Although many writers of historical fiction feel pressure to adhere strictly to the facts and figures, DuBois confessed this didn’t weigh on her mind: “When you are writing a book at the age of twenty-five,” she explained with a laugh, “you just don’t really think about anybody ever reading it. So I felt a lot of leeway just to take things that were narratively or dramatically effective or compelling and kind of excise things that weren’t.” In addition, she emphasized how Alexandr was only loosely based on Kasparov: “I tried to look at Kasparov as offering opportunity for various dramatic choices but not feel too wedding to his biography that I was tying my hands behind my back.”

DuBois on Writing and Publishing

Half an hour into our interview, I still couldn’t believe how young DuBois is. In all the years that Tethered by Letters has been publishing book reviews, I’ve only ever interviewed one other author under the age of thirty. So, of course, I was eager to hear her writing story and how she managed to achieve by the age of twenty-eight what most talented writers take the better half of their lives to do! Amused again by my astonishment, she began to tell me her story: “I always loved writing. I took creative writing classes in college, but I never really thought of it as a plausible career. I studied political science and philosophy…really sinking my money into something with economic opportunities,” she added with a chuckle, “but I applied to an MFA in fiction, not exactly on a whim, but because I was in that post-college year where I didn’t know what I wanted to do so I just sort of threw my hat in various ludicrous places and waited to see what happens. And then, I got to grad school, and making writing the center of my life felt really natural and satisfying and I was really happy. So that’s really how I got into writing.”

Although DeBois recognizes that MFAs aren’t for everyone, she’s very grateful for her studies. “I think it was a pivotal point because I got to immerse myself in writing…being able to have two years of your life dedicated to writing is an enormous gift. And you do learn so much. For me, it was a really precious and rare opportunity and it was hugely important.” It was during this time that she began work on A Partial History of Lost Causes, which took her three years to draft and a further year to edit and expand—“And that’s something that I’m sure would have taken me twice as long if I wouldn’t have been at IOM [Iowa Writers’ Workshop] and Stanford. That was pretty much all I was doing during those four years.”

Naturally, while most writers take decades to perfect their crafts, DeBois was still evolving while she was writing her novel. Confessing that there are aspects of the book she would have written differently now, she explained that it doesn’t affect the way she feels about it as a whole. “There is this first love you have when you write your first novel. I can see in it all this unrestrained passion and enthusiasm. I was just so very taken with my characters…There’s this dumbstruck feeling when you are very young and writing a book because you’re just obsessed with it. I think that’s something really sweet and special about that.”

This enthusiasm for her characters, oddly enough, did not materialize in a strict or structured writing process: “I’m really awful…I write a sentence and then I sort of wander away and then wander back and then check Facebook and then write another sentence, which is just a terrible way to write!” There is some method to her madness though. Instead of bouncing around chronologically, she focuses on one chapter at a time and, with A Partial History of Lost Causes, she wrote the entire book in order. “I’m organized and methodical on a macro level and then terribly schizophrenic on a micro level,” she concluded. “Sometimes I free-write nonsense and then wander away. And then I write three pages of dialogue and eventually it somehow emerges into a chapter…and then I write the next one…It’s such a strange alchemy. I feel bad that I can’t offer any concrete method.”

Even though she couldn’t instruct on process, she did have some advice for our TBL writers. After deep thought—determined to come up with something that wasn’t “utterly” platitudinous and trite—she eventually shrugged and concluded, “I think there are so many different paths to having writing at the center of your life: for some people the right decision is to get an MFA and for other people the right choice is to go as far away as possible. So I don’t know that I have any advice. People know if writing is something they need in their life, and if you know that, just keep doing it…I guess that’s pretty platitudinous and trite. Damn.”

Excerpt from A Partial History of Lost Causes

I beat my father at chess for the first time when I was twelve, and at first I thought it meant that I was brilliant. I danced around the kitchen, skidding in my socks, taunting him with his fallen kind, and it seemed unlike him not to laugh. My mother poked her head in to see what the yelling was about, and I said gleefully, “I beat Dad at chess.” My mother looked at my father, who was poring over the chessboard, his cheeks sucked in, his eyebrows clenched. “Did you let her win, Frank?”

“Did you, Dad?” I said, insulted. I sad down at the table and fiddled with the knights. They were my favorite, because they were best for sneak attacks. “You didn’t, did you?”

“No,” my father said, packing up the pawns, settling them in their foam for what turned out to be forever. “No, I would never do something like that.”

But how many of us would want somebody posthumously sifting through our past, looking for the first misstep? In retrospect, anybody’s eccentricities, charms, and mistakes can take on a darker dimension and become foreshadowing. All we can know is that my father’s mind was gone, by anyone’s standards, by the time he was forty. So I do not think my projections for myself are overly pessimistic.

If you’re interested in stories about what can be done in a short lifetime, the history of chess is not a bad place to look—it’s populated almost entirely by people who were at their best when they were barley out of adolescence. There’s Bobby Fischer, of course, though that story ends badly (with lunacy, exile in Iceland, and anti-Semitism) and Alexander Alexandrovich Alekhine, though that story ends badly, too (with alcoholism, erratic behavior, and more anti-Semitism). Then there’s Aleksandr Kimovich Bezetov, who was the USSR chess champion by the time he was nineteen, and the world chess champion by the time he was twenty-two. His is a sad story, too, in some ways, although I didn’t know that when I ran away to Russia to find him.